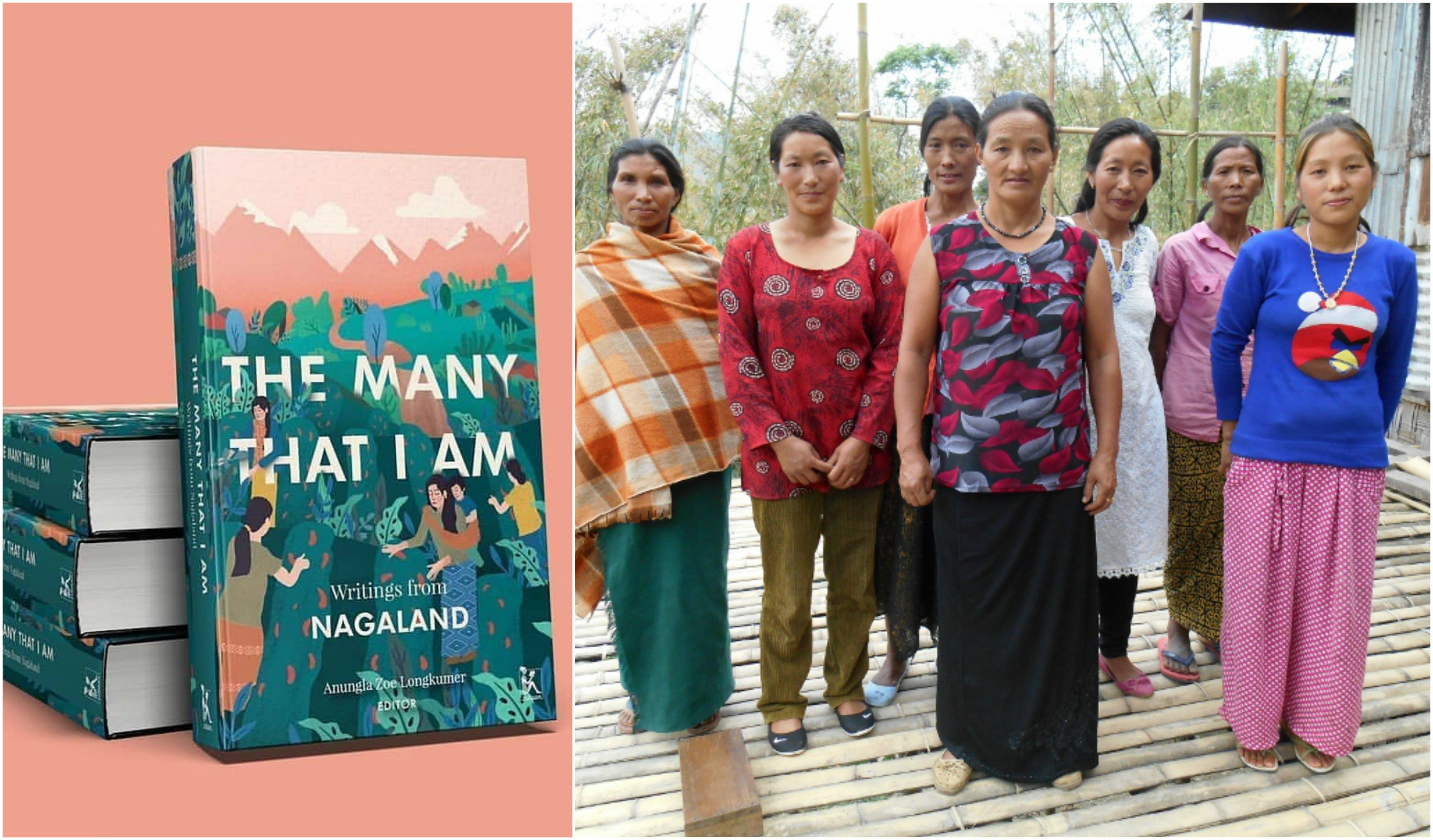

Beginning with, literally a print of an ‘acrylic on hand-woven nettle shawl’ and going on to traversing all the literary forms: short stories, personal essays, poems, slam poetry (performance poems), and each literary genre interrupted, and beautifully so, by painting prints, The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland edited by Anungla Zoe Longkumer (Zubaan, 2019) is a genre-defying book. The spread of literary genres in this anthology book reflects many a stories that describe the ‘world of women’ in Nagaland. Each sentence is chiseled to perfection in this gut-wrenching portrayal of Naga girls and women, their lives and stories.

When I read The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland, I thought why it feels quite like my grandmother telling me stories. It didn’t strike me until I re-read the ‘Introduction’ of this book where the editor notes “there is no tradition of written literature… […] What we have had through the ages is our oral tradition which encompasses everything about ourselves [.]”

When I dived in, into the sea of stories that The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland is, I knew that I’m in for trouble: How should I be reviewing it? There’s no way. How to dissect this book, which even if read in silos does have a story, but it’s the whole that’s making an impact that it had on me when I turned the last page of the book. You just need to read this book cover-to-cover to get acquainted with the struggles of a peasant to a modern-day, college-going Naga women; also, not leaving behind the tale-telling and tattoo traditions. Reading these stories can help you draw a mental map of Nagaland’s history: the long tradition of oral literature (storytelling), invasion by the Japanese army, rise of Christianity etc.

You just need to read this book cover-to-cover to get acquainted with the struggles of a peasant to a modern-day, college-going Naga women; also, not leaving behind the tale-telling and tattoo traditions.

A Literary Triumph

From Emisenla Jamir’s Where the Hills Grow Houses, the first story in this collection, till the end of the book this anthology is, as described in Yarla’s Tattoos by Sirawon Tulisen Khating, a teaching of how art paves way to formation of our own identity. Or may be destruction of the old one and building a new one instead.

“As a visual artist, this story opens a door in understanding the vast history of how design plays such an important role in creating identity.” — Yarla’s Tattoos, Sirawon Tulisen Khating

I enjoyed reading everything, in particular, Cherry Blossoms in April by Easterine Kire, a short story in The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland, an account of a Naga girl falling in love with a handsome, talk-of-the-town Japanese soldier. The story is as much about Naga hospitality as it is about falling in love even in hostile times as those described in this story. One of the lines that gripped me into rereading was this: “Despite the situation, their interest was aroused and they all endeavoured to get a look at this new officer.” Love, without meriting a testimonial for this, is not dependent on language.

“They [soldier and the women] were so happy together, laughing softly over their inability to communicate in words.” — Cherry Blossoms in April, Easterine Kire

In My Mother’s Daughter by Neikehienuo Mepfhüo, we find the perpetuating ‘excuse’ given by wives upon being beaten up by drunken, good-for-nothing husbands to their children: “Shhh… child. Don’t cry. Everything will be all right. He was drunk last night. It’s not his fault. It’s the alcohol in him that makes him do this to us.”

Also read: Book Review: Fragments Of A Life By Mythili Sivaraman

The story by Avinuo Kire, The Power to Forgive, besides being a narrative of the silent fight which a girl is fighting having being raped by her paternal uncle, is also about how a girl has to forget her past when she is getting married: “Sorting out her meagre belongings was the first phase of preparation for the new life she would soon embark upon.” Also, that she doesn’t complaint even the man is well into his mid-forties and unattractive, “ […] she was grateful that he had asked her at all,” as she is transferred from one institution of subjugation, her parents’ home, to another, her in-laws.

Several stories comprises of, and deftly deals with, multiple themes. Be it Sad Poems (April 2018), a poem, by Narola Changkija where the opening like sets the context: ‘I like sad poems,’ she says,/’they curl inside you/like unborn babies, no?’ Or be it When I Was a Girl (April 2018) where she writes, “When I was a girl,/the world was mystery and locked doors,/the keys hung out of reach.” Each word in this collection is poignant, and will linger in your hearts for a long time.

Besides this, first reason why this book should be read is that all 32 artists — writers, editors, graphic designers, painters, slam poets, and what not — whose work this book is, are women.

Why Read This Book?

In one of the prose pieces in this book (Storyteller by Emisenla Jamir), Otsüla, the Storyteller, wants to “leave behind stories with someone who knows their value.” Upon hearing this the kid, the narrator, watches dumbfounded as Otsüla smiles and removes upper portion of her head as if removing the lid of a bottle. And out comes a pot of stories, which she hands over to the kid to tell these stories, for she knows they’re valuable to her. It’s kind of magical, unreal yet believable. I think that’s true for someone who believes in the power of storytelling, if you’re one, you should read this book.

Besides this, first reason why The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland should be read is that all 32 artists — writers, editors, graphic designers, painters, slam poets, and what not — whose work this book is, are women. As the grandfather Tasu rightly mentions towards the end in Vishü Rita Krocha’s Cut Off, “How different the story is when women is around.” To realise this difference, you should read this book.

Secondly, The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland, is claiming back one’s roots. It’s an act of reinventing and rekindling the imagination of many a Naga girls and women; and, above all, upholding the tradition of keeping literature alive by infusing it with a fresh perspective. In the introduction the editor also notes that “this is the essence of literature and therefore even the slightest change or loss of any of these details renders that literature weak and incomplete.” Lastly, from the tales of getting beaten up by a myriad of circumstances, we’ve moments of triumphs as well in this collection. In one personal essay, When Doors Open by Eyingbeni Hümtsoe-Nienu we celebrate how one woman’s act of courage helped subsequent generations to bear fruit, opening the door of opportunity for her future generations.

Also read: Book Review: Gaysia–Adventures In The Queer East By Benjamin Law

So, every women, each of their stories — be it Martha’s mother, who is a political party worker and a strong-headed woman, or be it Vili who ignores the pang in her heart thinking of her runaway son by wearing a smile — make it a brilliant read. My sincere thanks and congratulations to all the women in the making of this book, who’re keeping aloft the torch of literary tradition, and also the women who taught me to read and write: Thank you!

Featured Image Source: Instagyou