Durga Puja and Dussehra, two festivals that define the Hindu community have more than just the timing in common. For one- the protagonist Ram plays a vital part in both narratives. Ram, the hero of the epic Ramayan, set out to wage a battle against Ravana in order to rescue his wife Sita whom the latter had kidnapped. He had prayed to Goddess Durga before he embarked on his journey to Lanka. To test his devotion, the Goddess had asked for 108 lotus offerings. Ram had 107 flowers, but as he was called Padmalochana or The Lotus Eyed One, He unhesitatingly reached out for His eyes intending to make that as an offering.

The conch shells and dhaaks(drums that are indigenous to Bengal) has been brought out from their resting places. The former has been washed inside out, the latter is fitted for their leather sheaths; new strings are tied- taut, stretched over the drum, crisscrossing crossing, forming a pattern that is as ancient as the instrument itself. The dhhaki has decorated the drums with a plume of feathers… Bengal has been donned with the colours of Durga Puja, the annual festival which has at its epicentre the ten handed Goddess- Durga. The air is rife with the sounds of the Dhaaak and conch shells, interspersed with ululation of women gathered to worship the powerful Goddess. They are not alone. Standing beside them are the men. Husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, friends…all standing before the Goddess praying, worshipping, offering her small tokens of appeasement…

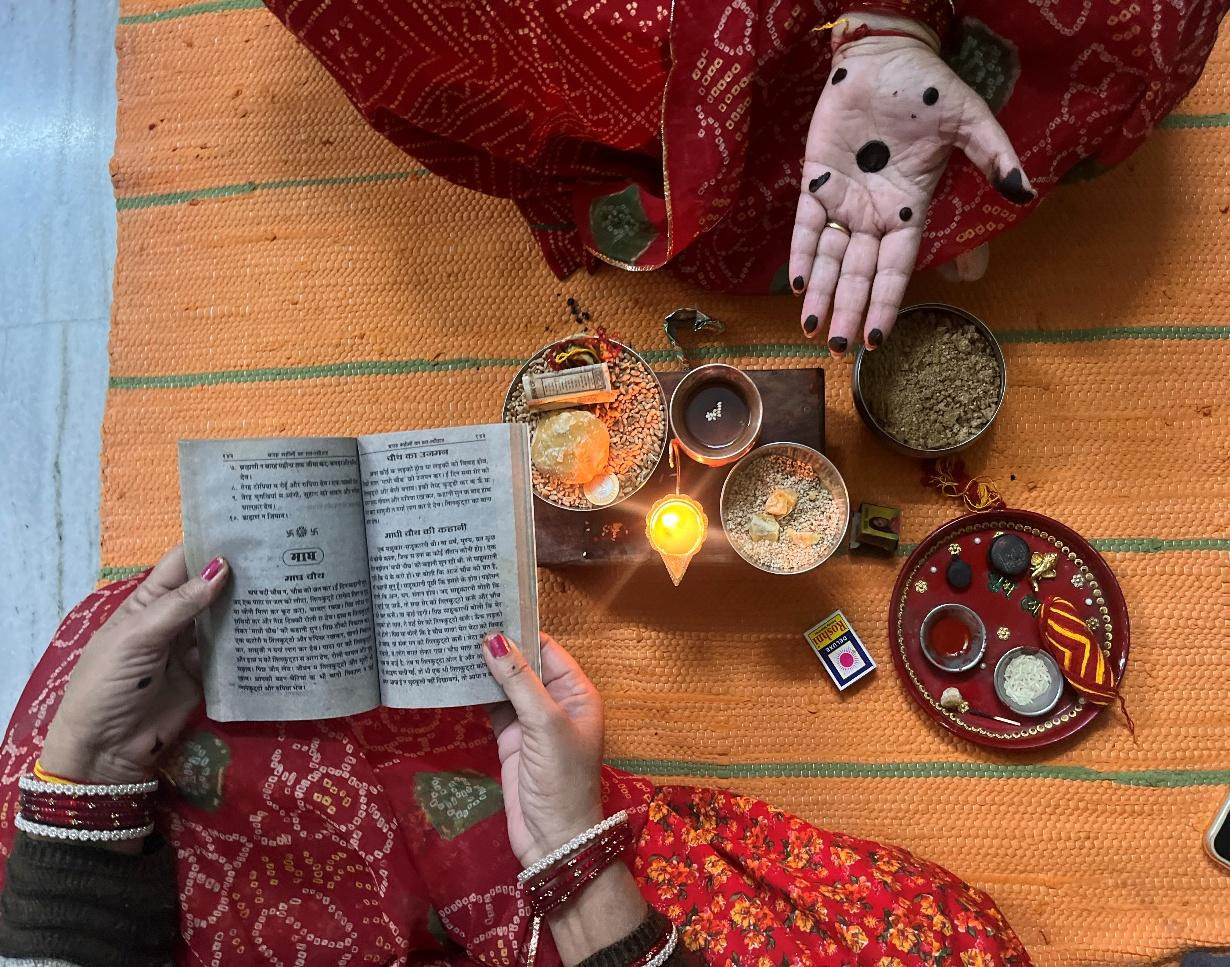

Outside Bengal the festive air is replicated in pockets where the Bengali Bhadralok (gentleman) rules. As the temperature dips and the orange stemmed shiuli or parijata flowers begin to bloom, the Bengali sniffs the air and misses his home, his childhood, the familiar landscape, the songs of his birthplace, the river Ganga flowing under the magnificent bridge…Nostalgia grips him and he comes together with the others to worship the Goddess. Everywhere the air is thick with the roll of drums, the chanting of the Vedic verses, the vapours of the incense as it weaves its way upwards even as the sounds of Rabindra Sangeet meander through the haze. Devotion and ostentatious display form the two parts of the festivities with Ma Durga firmly lodged in the very heart of the celebrations.

As Dashami rolls in, most parts of Northern India are agog with excitement because the day marks the victory of Shri Ram over the ten headed Demon King Ravana. Huge effigies of the demon king along with his brother Kumbhakarna and son Indrajeet are set up. Someone dons the dress and the blue make up and shoots flaming arrows at the effigies which are made of combustible matter. As the heads and bodies burst into flames, cries of Jai Shri Ram rent the air. People bow to the actor playing the part of Ram. Rationality, logic is suspended for an illusory moment and man and god truly become one.

In Ravana’s veneration, in the dilution of his villainous colours, the caste politics of modern day India is well articulated.

At this point the Goddess appears before Him, sufficiently pleased with Ram’s devotion and sense of sacrifice. She grants Him the boon of success. Ram thereafter conquers the evil Ravana. The prayer that He offered to the Goddess in the month of Ashwin finds replication down the ages in the festive occasion of Durga Puja. Ram’s demolition of Lanka, killing of Ravana and his clan is celebrated by people with ferocious fervour.

Ram – the ideal man, Maryada Purushottam and Durga, the Destroyer of Evil, The Golden Goddess are inexplicably linked. Both are after all symbols of power, the outcome of the caste based and patriarchal narratives. Valmiki Ramayan through its expert storytelling contains the subtext of the dominance of upper castes over the indigenous groups (who curiously also came to occupy the bottom rung of the caste structure). As caste struggles continue to rupture the social fabric of India, Ravana’s appropriation today by the lower caste and indigenous groups can very well be understood.

Ravana after all was not just about the destructive tendencies. He is shown through accounts in Indology and other versions of the Ramayan (like the Kamban Ramayan) to be a scholar, a devotee of Shiva, placed higher than even Shiva’s consort Nandi- The Bull. Plus he was known to be adept at playing the Veena. Ravana’s ten heads are about the passions and emotions that each of us is capable of. So apart from the intellect, Ravana contained within himself the nine universal emotions. This makes him as good or as bad as any of us. A complete man, capable of passions as well of intellectual displays. In Ravana’s veneration, in the dilution of his villainous colours, the caste politics of modern day India is well articulated.

Valmiki’s protagonist upheld honour, an outcome of the intellect. Matters of the affect occupied secondary status. So love and passion are put to the test of fidelity which satisfies the cognition even as they tear the heart and limbs with impunity. Ram is deified for this, venerated for this. Ravana played into the hands of passion, saw his sister bleeding through the nose, heard with simmering rage her account of how she was passed down to Lakshman when she went and spoke aloud of her love for the handsome Ram. His protective instincts were flared seeing his sister in this state of indignity. In a country where Rakshabandhan is celebrated as much as Dussehra, why was Ravana’s motive so hard to understand? Why were these incidents not used in the building up of the image of Ravana in popular discourses? A man who stands up for his sister must be celebrated, isn’t it?

Also read: Durga Puja: Whose Destruction Are We Celebrating Exactly?

However Ravana’s taking away Sita by force and deception, to settle a score is what makes him both an agent and victim of the patriarchal norms. His action was one of the patriarchal ruses which was based on the ideation that a woman’s labour and sexuality are owned by the man she belongs to. So revenge was effected on a woman’s physical and psychological self. The Agnipariksha was therefore a natural fall out in a society operating within this belief system. As we burn the effigies of Ravana, the questions refuse to fade into the ashes. Why is Ravana alone vilified for dishonouring and disrespecting a woman’s chastity? What is this chastity really? Who does it serve? And what about the proof of chastity that Ram demanded?

As we burn the effigies of Ravana, the questions refuse to fade into the ashes. Why is Ravana alone vilified for dishonouring and disrespecting a woman’s chastity? What is this chastity really? Who does it serve? And what about the proof of chastity that Ram demanded?

Mythology, especially the epics serve more than just entertainment. These are the unconventional ways in the the process of enculturation through which normative behaviour is passed down and ingrained in the social consciousness. As Sita took to the fire, she dragged along with her thousands of women. Through the stretch of time these women continue to bear the impact of the crucial test. Failure often ends in sanctioned honour killings. Ram—The Honourable God. Why did this God forsake one half of His followers?

And Durga Puja puts out yet another hypocrisy – the glorification of women. Men folding their hands, bowing in reverence to The Goddess. For five days they pray, they chant praises of the Goddess. As the clay Goddess departs, the one at home made of flesh and blood stays behind, doomed to a life of exploitation and subjugation. Ram showed the way to be honourable and every man emulates the Lotus Eyed God in a round- the- clock demand for chastity.

Every man demands absolute surrender from the women who surround him. He bows to the clay idol, and then unhesitatingly picks up the metaphorical (sometimes literal) cane to train his women into subjugation. We say we celebrate the feminine principle as we venerate the Goddess. The claim is ripped apart when statistics of crime against women trickle in. And left hanging in the air, mixing with the smell of incense and flowers, is the sense of diurnal humiliation and exploitation that most women feel as they navigate their lives.

Also read: The Tale Of Mahishasur And Durga: The Missing Story Of The Tribal Hero

Durga Puja and Dussehra, festivals that define our identity as members of the Hindu community, that create a mood of joy and celebration also exposes the patriarchal underpinnings of society. Sniff the air…it’s unmistakably there.

Featured Image Source: Hindustan Times

About the author(s)

Saonli Hazra is an educator and runs Words’Worth. She is a government-approved trainer for English and also a freelance writer for Times Publications. She can be reached at saonlihazra@yahoo.com.