There’s more to Kashmir than its natural beauty. And this other side or sides are well articulated in Sahba Husain’s Love, Loss, and Longing in Kashmir (Zubaan, 2019). It is the most militarized zone in the world and, with a new inhumane lockdown and revising the applicability of Article 370 on 5 August 2019, there’s no communication from and with Kashmir. (Please note that the Article 370 of the Indian constitution hasn’t been abolished. The mechanism of its applicability has been changed making it defunct in the Valley.)

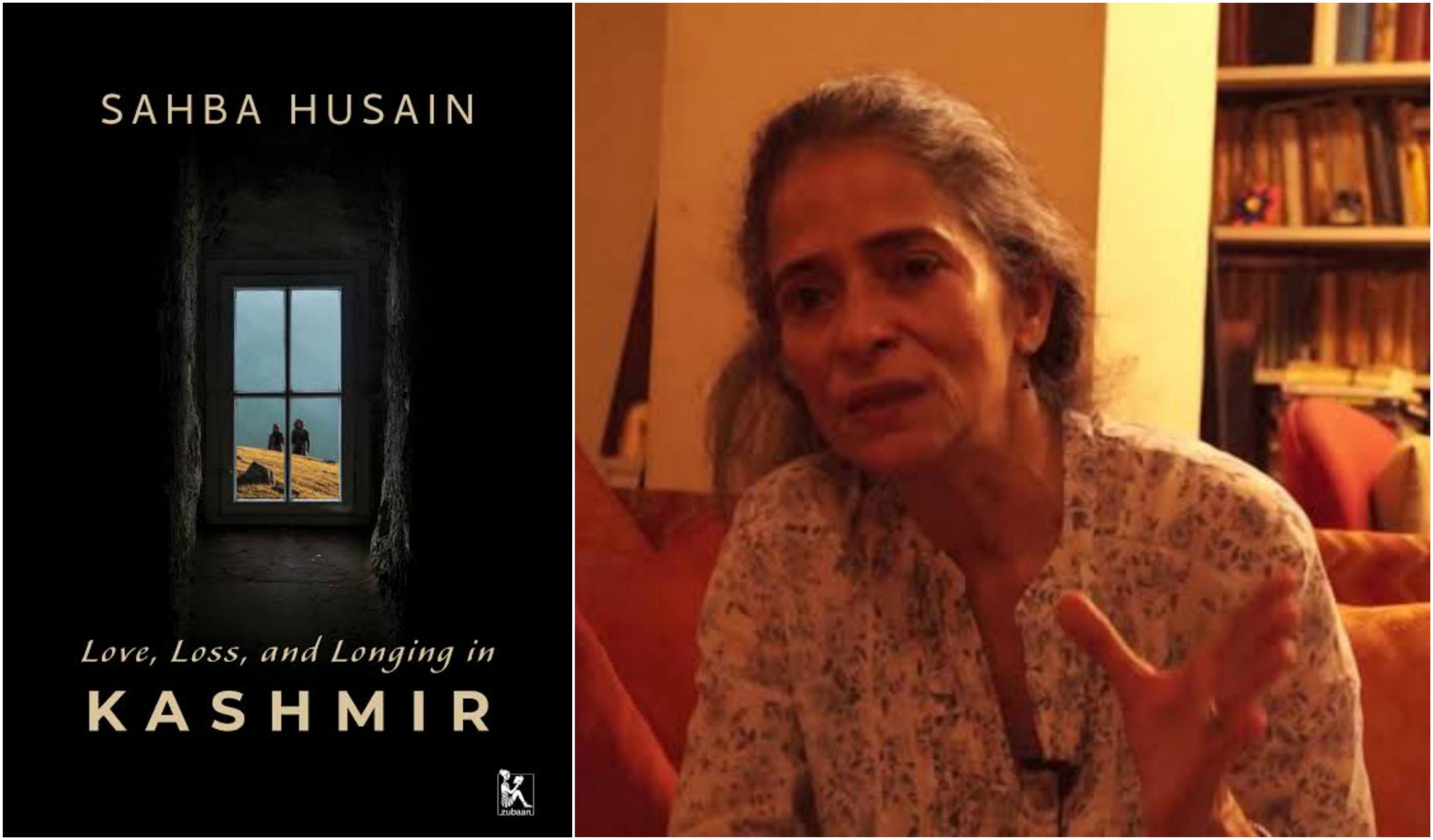

Having worked as a consultant—Oxfam India Trust for its Violence Mitigation and Amelioration Project (VMAP) and Aman Public Charitable Trust under its Gender, Mental Health and Conflict Program— Sahba Husain has been writing on Kashmir since 2000.

Image Source: YouTube

Breaking the Stereotypes

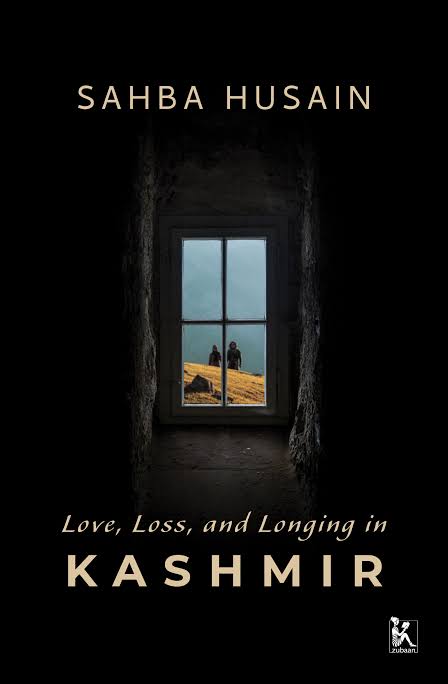

Her book invokes a new sensibility toward Kashmir. Almost all the books that I’ve read on Kashmir have a book-cover stereotype: a Shikara, an empty Shikara, an old man rowing a Shikara, or a sunset scene and an old man rowing a Shikara, and last but not the least an army personnel looking through a barbed wire with a gun in hand. All these created a sad-beauty sort of a fetish of Kashmir. However, even the clothing of books demand much more examination at a deeper level. The beautiful cover, which shows an alley leading to a glass door through which we can see a man and woman treading on a meadow, is designed by the daughter of Sahba Husain—Saema Husain.

It’s important to talk about stereotypes such as the one that asserts that Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims cannot stay together in harmony, that Kashmiri Pandits were driven out by Kashmiri Muslims, that the India Army is there for the greater good etc. These stereotypes give rise to further issues, whereby people expect the presence of absolute academic objectivity while writing about Kashmir. However, a land that has sustained and endured extreme violence needs no stone-hearted researcher but an empathetic listener.

These stereotypes give rise to further issues, whereby people expect the presence of absolute academic objectivity while writing about Kashmir. However, a land that has sustained and endured extreme violence needs no stone-hearted researcher but an empathetic listener.

And I was elated to know one in Sahba Husain, in person, during the closed book launch in India International Centre, Delhi where she mentioned, “I knew I could not remain neutral or objective any more, although objectivity in research in much valued but here it was imperative for me to take a position – politically and emotionally – and it soon became clear to me where and on whose side I stood: by the side of the people and their struggle for justice.”

Also read: Kashmir, My Home: In Conversation With Ahmed Dar

Kashmir Is Bleeding, Screaming and Fighting All by Itself

This book is broken down into five chapters. First dealing with the departure of Kashmiri Pandits; second with enforced disappearances; third about the presence of women in Tehreek (movement); fourth on the mental health of the Kashmiri people; and fifth, the final one, on the sexual violence and impunity in Kashmir.

Discussing about the sudden departure of Kashmiri Pandits (KPs), Sahba Husain also uncovers other facets that do not form the agenda of the Prime Time news channel debates by recording testimonials of KPs, both who have stayed and left. Testimonies like people mentioning unequivocally that they “have continued to stay here because of [their] Muslim friends and colleagues who provided [us] with a sense of safety. They in fact helped us survive through the worst periods of militancy. There existed mutual support and understanding between us.”

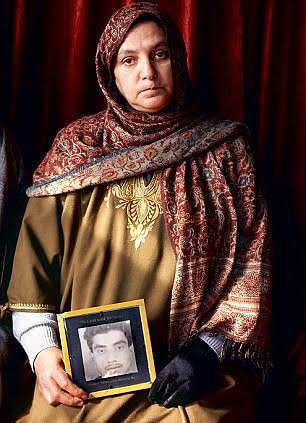

but I’m purposefully doing away with citing figures. Numbers can never tell the separation that tears apart Parveena every second, that longing she has to meet her son.

Kashmir is a tragedy unfolding itself almost daily. It hides under its belly the pain and separation of all its women and this feeling is poignant when we read the story of Parveena Ahangar whose 16-year-old was picked up by the Indian National Security Guard in 1990. He is still missing.

“Women have suffered more than anybody else during the last many decades, as she [sic] had to bear onslaught of oppression more than the men.” — Yasin Malik

The book also has figures and statistics of enforced disappearances, state of mental health facilities and figures on Kashmiri Pandits, and violence against women; but I’m purposefully doing away with citing figures. Numbers can never tell the separation that tears apart Parveena every second, that longing she has to meet her son.

“Everyone I met had a plastic bag ticked away in the house, which they pulled out to share the newspaper cutting sand photographs that it contained. These plastic bags were a precious possession for the women for they contained not only memories but also proof of the existence of the disappeared person.” — Sahba Husain

Numbers can never explain their tragedy that has hit each one of the Kashmiri population — its men, women and children alike. Besides women, Sahba Husain also highlights the plight of men who are prone to sexual violence by the military. She writes, “Sexual violence against during war/conflict remains largely invisible. Like violence against women, sexual violence against men is nearly unspeakable in its brutality.”

Also read: The Often Untold Journeys Of Mental Health Issues In The Kashmir Valley

Reading this book has affected and appalled me. With this unprecedented and, at least till 2024 likely irrevocable, inhumane lockdown, I’m not sure what to do. But anyway, I can just appeal all of us to arm ourselves with information to be the “real changemakers” and not pseudo-allies by reading books on Kashmir. And this is an essential book.

i enjoyed reading this review.