Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.

Editor’s Note: This article was written for the #GBVinMedia Campaign, which interrogates mainstream media’s reportage of gender-based violence from an intersectional feminist perspective. Many of these insights are based on the #GBVinMedia toolkit, released by FII as a guide for journalists and media professionals to report gender-based violence sensitively and ethically. If you wish to get in touch regarding this campaign, please email asmita@feminisminindia.com.The gruesome gang-rape and murder of the 27-year old veterinarian doctor from Hyderabad has mobilised the country into demanding a safer environment for women. A large part of this catalysis and public outrage has happened thanks to the media. The case has captured the attention of national and international media and has been reported almost hourly by one media outlet or another. A media spotlight on rape can be transformative to a much-needed public conversation on rape and gender-based violence in our country.

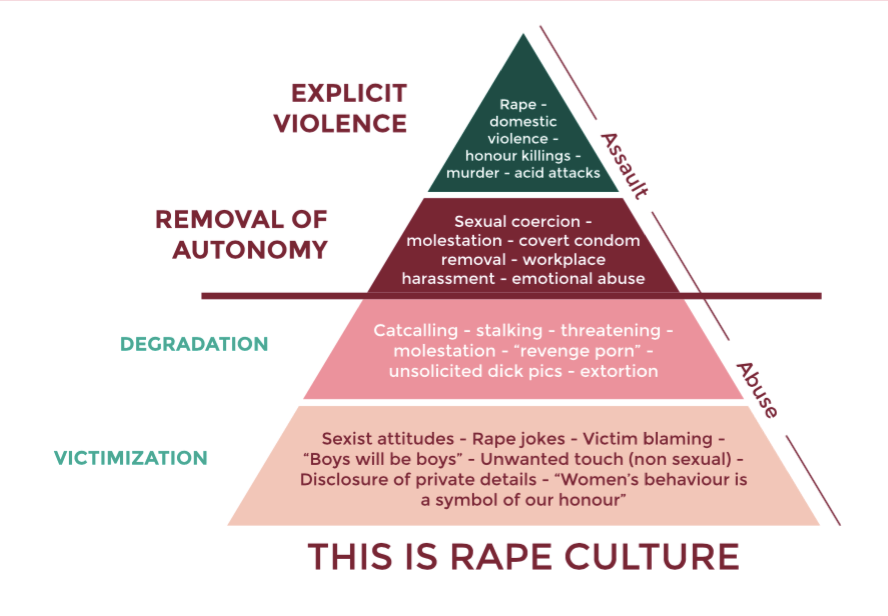

However, the sensationalism that this case has garnered, which has been fuelled by the media, does not push for this self-critical public conversation that our country needs. Instead, it externalises the problem and promises a solution through swift trials, and grisly punishments. This stems from a tone-deaf understanding of gender-based violence – one that fails to view the Hyderabad rape-murder case as the pinnacle of a rape culture pyramid that is buttressed by a society that views women as inferior beings and normalises violence against us from the moment we are born.

Also read: Does News Framing Change How We Understand Rape?

Let’s look at some of the pitfalls that I’ve noticed in the coverage of the Hyderabad rape-murder case.

1. Uncritical demands for death penalty/lynching/castration

Whenever a rape case captures the country’s attention, calls for the death penalty are not far behind – provided of course, that the perpetrators of the crime are not high-profile individuals with any sort of clout. Our blood-thirst for revenge is limited to lorry drivers and mechanics, but not actors, politicians or our husbands, fathers and uncles – many of whom are convicted for rapes and murders as grisly as this one. (A feminist colleague wryly commented about the outrage that the victim’s charred body in this case sparked. Dowry deaths, where brides and young women are burned to death almost daily in our country, inspire no such outrage, because that would require an actual introspection into our cultural norms.)

The media can mobilise outrage and the demand for justice without calling for the death penalty.

The death penalty has been routinely and severely criticised by feminist and legal scholars as being counterproductive, discriminatory and focused more on revenge-taking than building a safer society. However, in the past few days, we have had Rajya Sabha MPs like Jaya Bachchhan demand a public lynching of rapists, P Wilson asking for chemical castration and a more general demand for capital punishment voiced by politicians and other figures of authority.

The media has uncritically paraphrased these demands, with calls for death penalty and more gruesome variations of the same dominating the headlines of newspapers in the past few days. Yes, they are the opinions of politicians that the media is reporting about, not the media themselves. However, when these opinions are broadcast without a single line about the pitfalls of the death penalty, then public opinion too echoes this sentiment. A simple way to counteract this is to include a quote by a feminist scholar or a legal expert that balances the bloodthirsty revenge discourse with a more nuanced understanding of how to combat gender-based violence. The media can mobilise outrage and the demand for justice without calling for the death penalty.

Times Now, however went one step further than reporting these politician’s quotes. Fuelled by the bloodlust against these rapists, their Twitter platform hosted open polls asking the public about their views on lynching rapists. Using a crime that reflects the rot in our society to earn Twitter engagement points is a low bar, even for this channel.

2. Sensationalising the Hyderabad rape-murder case

Rape and gender-based violence is usually a traumatic incident. When a case is covered and reported as much as this one, this trauma can spill over onto society – we feel sadness, shame and anger for letting such a crime take place. The media ought not to capitalise on this trauma by turning this horrific crime into a spectacle.

Also read: Why Are Sensationalist Headlines Of GBV Cases A Problem?

Certain media headlines seem to revel in the brutality of the crime, with clickbait headlines promising more details about the grisliness of the crime within the article. Crime turns into entertainment, and the Hyderabad rape-murder case just another day in the TRP industry.

3. Use of her name and image

It is illegal, under Section 228A of the Indian Penal Code, to release the name or other identifiable information about victims of rape and certain other crimes of sexual violence, in order to reduce the stigma that rape victims and their families live with. However, the name of the victim of the Hyderabad rape-murder case was released, making a national Twitter trend within hours. Several media houses have also been using her image, taken from her Facebook profile. Her identity was released in the gap between her finding her body (while it was still thought to be a case of murder alone) and the police confirming that it was a case of rape. However, as soon as the rape was confirmed, media houses ought to have retracted her name and stopped its further use, which did not happen.

The public, increasingly desensitised to rape as a crime, should not need to see a charred body in order to feel shock and sympathy about this rape.

Worst of all, images of her charred body have been used to create outrage and spectacle over this crime. The public, increasingly desensitised to rape as a crime, should not need to see a charred body in order to feel shock and sympathy about this rape. Using this image depicts the victim in the most horrific moment of her life and death, and robs her of dignity in death. The image can also be exceedingly triggering and traumatising to her family and friends, as well to survivors of gender-based violence in general.

In the #GBVinMedia toolkit, we suggest the use of images that show women protesting against rape, saying no, or otherwise portray women in positions of strength and resilience as opposed to fearfulness, vulnerability and helplessness that stock images used by media houses routinely portray.

4. Who is reported about?

After the 2012 gang-rape and murder of Jyoti Singh Pandey received the outpouring of public support that it did, many thinkpieces analysed why this was so. Brutal rapes and murders are, unfortunately, a nearly daily reality in our country. Why did this case receive so much attention?

In one such study, a Times of India reporter is quoted saying that media offices give stories attention if they are about ‘PLUs’ – People Like Us. With newspapers being staffed largely by urban-dwelling, upper-caste and middle/upper class staffers, stories that receive coverage are overwhelmingly of victims/survivors that match these social parameters. This urban bias means that thousands of rapes from other parts of the country, of survivors that are not upper-caste and middle/upper-class, go unreported. In a different study about India’s reportage of gender-based violence, scholars Amanda Gilbertson and Niharika Pandit found that 93.4% of articles published about gender-based violence were located in urban areas.

Some scholars surmised that Jyoti Singh Pandey was the “ideal victim” – the India’s daughter that the country could rally behind. She was not out too late, she was not alone, and she was from a middle-class family. In the words of this LiveMint thinkpiece, “she was someone aspirational India could and did empathise with”.

This urban bias means that thousands of rapes from other parts of the country, of survivors that are not upper-caste and middle/upper-class, go unreported.

Another key reasons that 2012 Delhi gang rape case received so much coverage was because it reinforced the myth of “stranger danger” – i.e., rapes happen by unknown men outside the house, leading to the “solution” being that women should stay at home in order to avoid getting raped. This is at odds with reality, with NCRB data showing that 94.6% of reported rapes happening by someone that is known to the survivor, such as partners, neighbours, family members and colleagues. Men from marginalized communities, like Dalit and Muslim men are also implicated in this ‘stranger danger’ framing, seen as more dangerous and violent than men from dominant castes, classes and religions. However, stranger rape is the most palatable form of rape, since it allows us to train our focus away from our own communities, societies and families and onto the working class and marginalised male.

Each of these three reasons applies in the Hyderabad rape-murder case as well. The victim was on her way home from work, not engaged in anything “disreputable” that could be used to blame her for “inviting” the violence, and was attacked by stranger (and lower-class) men. She was a victim that India could unanimously rally behind, as we should. But what of the thousands of other women, who may not fall in this “ideal victim” category that also require our support?

Two days before the Hyderabadi woman was murdered, a Dalit woman hawker was similarly gang-raped and murdered in Adilabad, which is just a few hundred kilometres away from Hyderabad. While local Dalit and Adivasi groups have been protesting the gang-rape and murder, there are only a smattering of news reports about it. The media ought to take a concerted effort to ensure that it doesn’t conform to the urban bias that is so evidently visible in media trends.

With the national spotlight on rape and gender-based violence in our country, a more sensitive, informed and nuanced perspective by the media can make a real dent in our patriarchal social fabric. It is my hope that the media steps up to this opportunity in its coverage of the Hyderabad rape-murder to make a real change.

About the author(s)

Asmita is a Freelance Communications Consultant, and specialises in leading digital advocacy campaigns for social and gender justice issues. When not using social media for work, she uses social media for fun (and a healthy dash of existential despair).

Cliche!!!

I am a 16 year old who’s questioning her gender and sexuality and i’m a raging feminist. I live in a very “traditional” stereotyped society. I remember discussing about this after a male teacher sympathized with the rapist’s family. The boys of course, they weren’t interested. While the girls were convinced that “half” of the fault goes to the victim for “trusting strangers” and “Going out alone” thus inviting trouble. Most of them ignored this, but the people who did get involved blamed her “carelessness” as the sole reason for this heinous act. They told me that she should have been careful as we know “how the society is like and how it’ll always be” and they also told “since we cannot change the society, we should be careful.” I had tears in my eyes during that, this is RAPE CULTURE. Its 2020 and the students of my age are still uneducated about this culture. Now I’m not surprised that they now discriminate me for my gender and sexuality.