“Ye dukh kahe khatam nahi hota be!” (Why this sorrow never ends) exclaims a Dalit character Deepak (essayed by Vicky Kaushal) after the tragic demise of his girlfriend in the 2015, critically acclaimed film Masaan. The same words can be put in the mouth of a character from a Dalit story by non-Dalit writers like Premchand and Mulk Raj Anand. This is because one of the most cliched representation of Dalit characters by non-Dalit writers has been in their doleful exaggeration of suffering of Dalits where their life has no escape from “dukh”.The major point of contention by Dalit writers against non-Dalit representations has been the latter’s pitiful, sad and melodramatically sympathetic representation of Dalit characters. Dalit critics argue that such a portrayal is far removed from the revolutionary aspect of Dalit literature which seeks to close the narrative not with a miserable ending but with a protest. Initial attempts at writing about Dalits by authors like Anand (in his famous novel Untouchable) and Premchand were well intentioned but their characters lacked one of the most essential elements of a Dalit text: the presence of a Dalit chetna (Dalit consciousness). It was Marathi writer Baburao Bagul’s anthology Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (When I Hid My Caste) that heralded a brave new voice in the Dalit literary sphere.

Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (When I Hid My Caste)

Author: Baburao Bagul

Publication Date: Originally 1963 (English Translation by Jerry Pinto released in 2018)

Publishers: Speaking Tigers

Baburao Bagul, as noted by Shanta Gokhale in her Introduction to the anthology, grew up in Maharashtra amidst poverty and destitute conditions. Himself a Dalit, Bagul was profoundly inspired by the revolutionary ideals of both Marxism and Babasaheb Ambedkar. Publishing his collection of short stories in 1963, Bagul’s bold, angry and revolutionary stories raised a storm in the Marathi world. Far from being just sad and pitiful accounts of Dalit lives- Bagul’s words blazed with rage against the horrors of the caste system. His protagonists, unlike Dalit characters by savarna writers, were strong, bold and defiant, questioning and defying authority at every step. In their influential book The Exercise of Freedom: An Introduction to Dalit Writings, K Satyanarayana and Susie Tharu have noted the impact of the book where it was soon labelled as “the epic of Dalit Literature”.

imself a Dalit, Bagul was profoundly inspired by the revolutionary ideals of both Marxism and Babasaheb Ambedkar. Publishing his collection of short stories in 1963, Bagul’s bold, angry and revolutionary stories raised a storm in the Marathi world. Far from being just sad and pitiful accounts of Dalit lives- Bagul’s words blazed with rage against the horrors of the caste system.

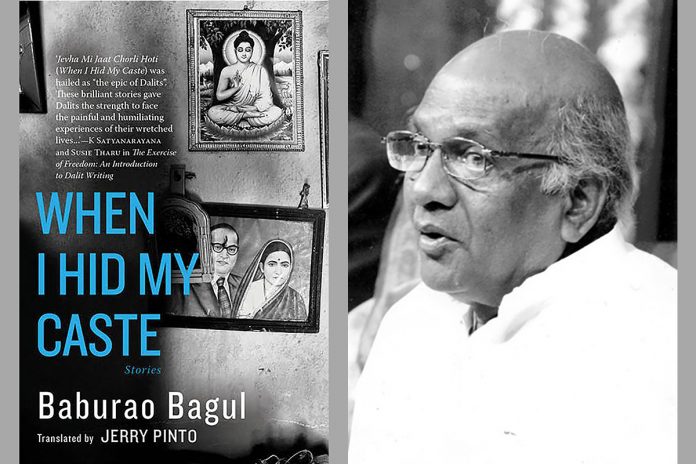

Almost half a century later, Bagul’s stories have finally been translated by acclaimed writer-translator Jerry Pinto. With its title written in bold blue cover against two photographs: one of Babasaheb Ambedkar and the other of Buddha, the very copy of the epic anthology by Bagul seems to hold some kind of sacred reverence for the subject it seeks to portray.

Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (When I Hid My Caste) holds ten short-stories and in the following review, I would specially like to focus on those that deal prominently with the caste question. But even in stories where Bagul doesn’t talk about the horrors of caste, he poignantly explores the question of what it means to be an outsider in a rigid society. Whether it be the intimidating Ethiopian outlaw in the story “Gangster” or the prostitute Girja trying to collect money for her ailing child back in the village in “Streetwalker”, Bagul tries to bring all those regarded as pariahs from the periphery into the center, as if to show that these people too exist.

“When I Hid My Caste”

Bagul’s titular story of the collection, “When I Hid My Caste” begins and ends with raging statements, while simultaneously exploring the more complex dynamics of casteism in urban India.

The story is centered on Masthur, a Dalit man who is elated to get a job at Udhna Railway Station in Surat. Masthur, easily gullible a man, inherits the idea that a job in a city would promise a greater happiness in life, equating the idea of economic upliftment with social happiness. However, he soon realizes that the city is not free from its caste bias where people are ready to “eat mud with a caste brother” but not even a “feast with someone of a lower caste.” Masthur hides his Dalit identity and with his poetic skills wins the appraisal of an upper-caste man Ramcharan who ends up hero-worshipping the former and invites him to his house for dinner.

However, his caste is eventually revealed by the story’s end making him the victim of caste-based violence by Ramcharan and his group. Masthur is eventually rescued by a fellow Dalit, Kashinath towards the end of the story. When asked if they should go to the police station, Masthur refuses to prosecute his perpetrators and proclaims:

“When was I beaten by them? It was Manu who thrashed me.”

Also read: Why You Need To Stop Asking Dalits “Do You Face Caste Discrimination?”

The story’s angry denouement comes off as a scathing criticism against religious texts (especially Manusmriti) which have legitimized caste-based violence. Can Dalits really hide their identity in a country engulfed by caste?, is the question Bagul raises in the story. It also points out that even the acquisition of knowledge, power and economy can never dispel the monster of caste.

“Dassehra Sacrifice”

“Dassehra Sacrifice” lacks much plot action and is centered on the sacrifice of a buffalo during the festival. The mad buffalo to be sacrificed is being controlled by two strong Dalit men, Deva and Shiva, while the honor of beheading the buffalo is to be performed by the upper caste Patil who instead of being presented as the macho, brave and heroic man is presented as a timid fellow intimidated by the sight of the raging bull. While the Dalits in the story risk their lives to control the buffalo, it is ultimately Patil seated on a decorated horsewho gets to kill the buffalo in the end despite having done nothing at all. Bagul however succeeds in creating a parallel account by making a larger case, showing how Dalits have always been the backbone of the society cleaning the mess created by upper-caste men, who end up enjoying the honor.

Bagul however succeeds in creating a parallel account by making a larger case, showing how Dalits have always been the backbone of the society cleaning the mess created by upper-caste men, who end up enjoying the honor.

“Bohada“

“Bohada” opens with the Dalit protagonist Damu, a Mahar asking to perform a dance in the village festival. The upper caste people are horrified at his suggestion and some are even hostile at this request but cannot deny Damu the right due to the village Collector’s warning against caste-based discriminations in the village. The upper caste men hatch a strategic plan and ask Damu to pay a sum of Rs.200 if he wants to perform.

This is where Bagul’s continuation and conclusion of the story becomes interesting. Instead of letting Damu moan and grief over an opportunity denied by the caste system (as a non-Dalit writer would have done), Bagul shows how Damu manages to not only get the requested sum but also ends up winning the cunning bid exercised by the upper caste men. Bagul begins the story in a somber mode where the fulfillment of Damu’s choice seems like a distant dream but the trope of the melancholic defeat is subverted to make way for an empowering saga.

“Revolt”

“Revolt” reflects a youth Jai who influenced by Ambedkar opposes his parents’ effort to make him work as a manual scavenger-cleaner. Jai is adamant on his decision and wants to finish his education but his father remains skeptical of his son’s education and wants to “dispel the white collar dreams his son had been nurturing”. The conflict between father and son forms the major plot of the story as Jai rebels to continue on his education and break the tradition. The story while emphasizing the importance of education also brings a critique of the unjust division of labor imposed by the caste system. Again, the story demands comparison with Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable whose protagonist Bakha lacks the iconoclastic zeal displayed by Jai in the story.

Also read: Dalit Women Learn Differently: Experiences In Educational Institutions

Reading Jevha Mi Jaat Chorli Hoti (When I Hid My Caste), it is no difficult task to see why it has been rightly labelled as one of the most crucial Dalit texts. Bagul not only represented the Dalit characters as they are, but also offered them with possibilities of what they could be.

Featured Image Source: Modern Literature