Like every other domain in the world, medicine has also historically been male dominated. Early research, experiments and developments were all done by men and for men. Women came into the picture only as an aberration of a male body. For most of modern human history, men have dominated the public world while women have been to take care of the house and its members. When women did start participating in the public world of medicine, they were first and foremost nurses. Nursing was equated to caring and therefore thought to be an appropriate job for women.

Now fields of medicine that are considered ‘soft’ like paediatrics and dermatology, and obstetrics and gynaecology, which explicitly cater to the female body, are the fields female MDs (Doctor of Medicine) dominate in. Departments like cardio-thoracic (heart and lung) surgery and neurosurgery are still the domain of men as they are considered more complex. In India, where still a much larger percentage of women graduate with degrees but don’t hold paying jobs, one young woman in the 1880s paved her way to become the first Indian woman to gain an MD in western medicine.

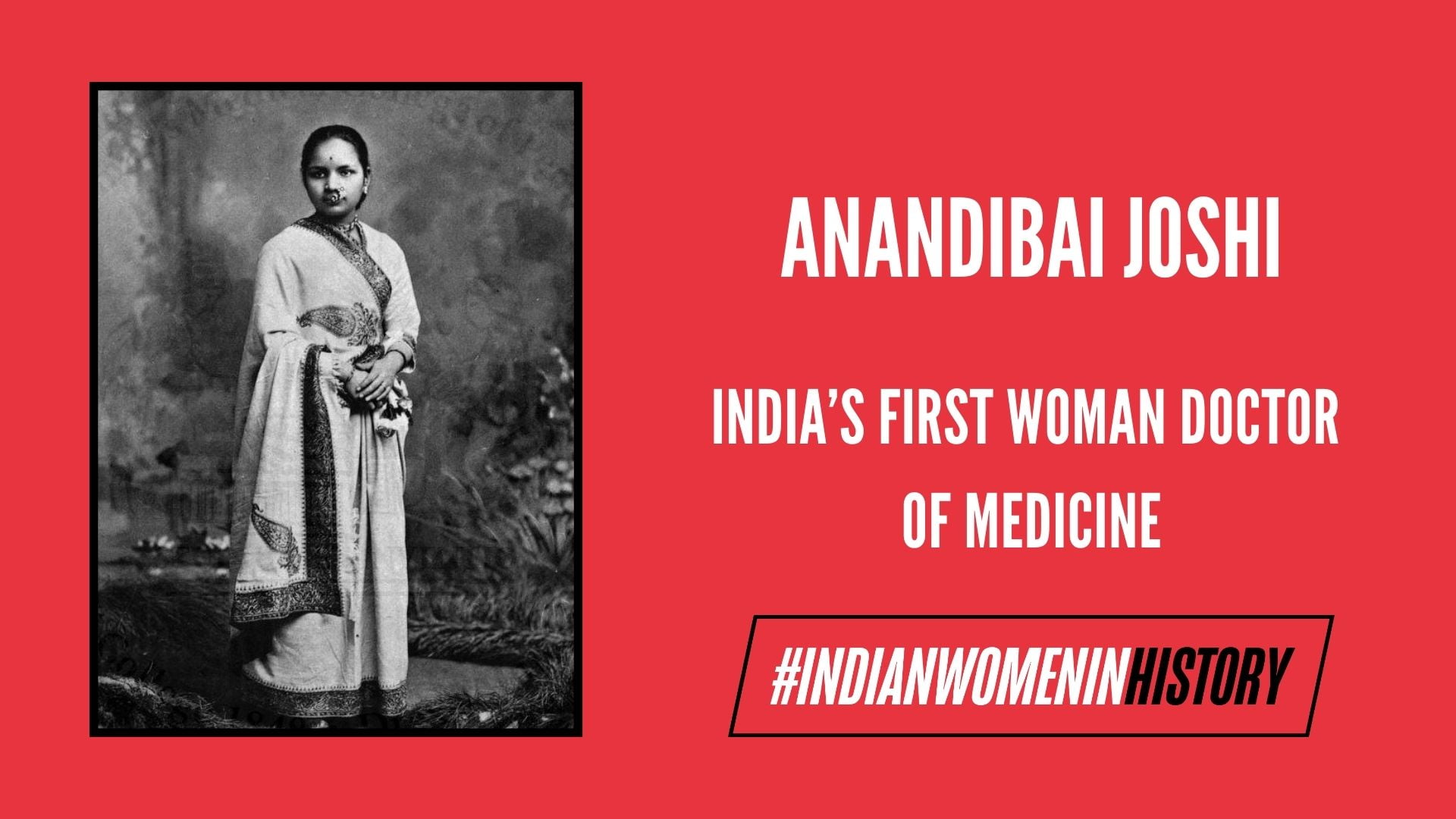

Anandibai Joshi was born into a family of impoverished Marathi landlords in 1865 in Kalyan, Maharashtra. At the age of 9, she was married to a widower 20 years her senior, Gopalrao Joshi, who worked as a government clerk. He was progressive for his times and was a supporter of women’s education.

At the age of 14, Anandibai gave birth to a child who lived for only 10 days due to lack of medical care. This inspired her determination to become a physician and help other women in similar positions. When attempts to enrol in missionary schools did not work out, Anandibai And Gopalrao Joshi moved to Calcutta (erstwhile Kolkata) where she learnt to read and write in Sanskrit, as well as English. For the next step, they decided to look for a medical college in the west as Anandibai felt ayurvedic knowledge and midwifery was not nearly enough to help with complicated pregnancies and births and because there was no institute of western medicine that accepted women in India.

A letter was sent to Royal Wilder, a well-known American missionary stating Anandibai’s ardent desire to study medicine and inquiring for a position for Gopalrao in the United States. This letter was published in the Princeton’s Missionary Review where it caught the eye of a New Jersy resident Theodicia Carpenter, who decided to help Anandibai. Through her, Anandibai and Gopalrao met a physician couple called the Thorborns who suggested a medical college for Anandi and also help her arrive in the US. Theodicia and Anandi later developed a close friendship, starting from even before she left for the US and came to address each other as ‘aunt’ and ‘niece’.

If her being a married woman going alone to a foreign country to study Western medicine was not blasphemous enough for her community, she was also a Brahmin and they believed that once Brahmin crossed the ‘seven seas’ they would lose their caste. Before leaving for the US, Anandibai addressed a local community hall justifying her decision. She pointed out the lack of female physicians and emphasised that only Hindu women physicians could help Hindu women in need. She volunteered to be the first to become one.

Education in the US

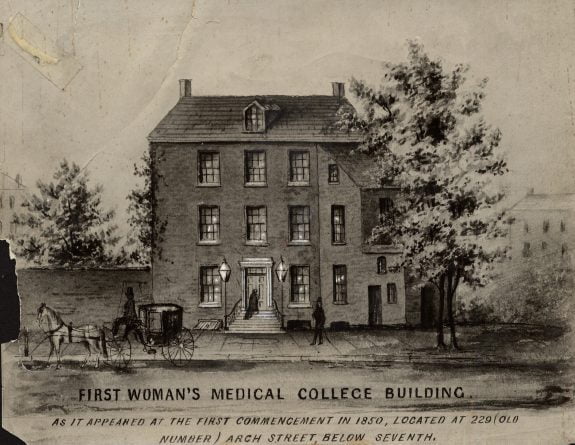

Gopalrao could not secure a position for himself in the US. Anandibai left India in 1883 with two acquaintances of the Thornborns. There, she applied to be enrolled in the medical program of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. At the age of 19, she started her medical education and three years later, at the age of 21, graduated with an MD in obstetrics. Her MD thesis was titled ‘Obstetrics Among the Aryan Hindoos’ where she incorporated elements from both Western medicine and Ayurveda.

Her husband made it to the US for her graduation. Pandita Ramabai also attended her graduation, where she was declared to be the first woman MD from India. She also received a congratulatory message from the then empress of India, Queen Victoria. Along with her, two other graduates, Kei Okami from Japan and Sabat M. Islamabouli from Syria also became the first women from their respective countries to gain MDs in Western medicine from a Western university.

Return to India

The cold weather, lack of suitable winter clothes and unfamiliar food and environment took a toll on Anandibai’s health. She had spells of fainting, high temperatures and a constant cough. It was discovered that she had contracted tuberculosis and was admitted to the Woman’s Hospital in Philadelphia. The doctor there advised that Anandibai go back to India where the climate would suit her better. In 1886, she and her husband returned home, reaching India in late 1886.

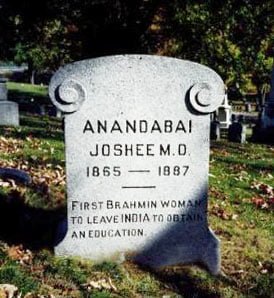

Back in India, she was given a hero’s welcome and was appointed as the physician in-charge of the women’s ward in the Albert Edward Hospital by the princely state of Kolhapur. Soon however, her health grew much worse. Early next year, she died in February 1887, just before turning 22. Her death was mourned by the whole country and her ashes were sent to Theodicia in the US who had them buried in her family cemetery in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Legacy

Anandibai Joshi was a pioneer in her own right. In times when the only thing a woman was supposed to do was get married and take care of a family, she broke many social norms and acquired a medical degree from a foreign country. She did not let her infant’s son’s death discourage her but developed unwavering determination to do something to help other women in the same situation she was in.

Multiple media houses have adopted her life-story into movies and serials. Most recently, a Marathi biopic called Anandi Gopal was released in 2019. The Institute for Research and Documentation in Social Sciences (IRDS), an NGO from Lucknow has been giving out the Anandibai Joshi Award for Medicine. Additionally, the Government of Maharashtra also established a scholarship for women working on women’s health projects. She also has a crater on Venus named after her, called ‘Joshee’.

Anandibai Joshi was a torchbearer of the movement that led many more Indians, especially women, to access education at par with their colonisers. Her resolve to achieve something even powerful men of her time did not dream of, led her to become something much greater that her life originally would have amounted to had she been content with being a wife and a mother. She might not have been termed a feminist but she was well enough one, inspiring many more generations of women to follow their dreams.

About the author(s)

Shatabdi is a second year student in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Madras. She loves the colour yellow, talking, and the eureka moments she gets once every few moons. Her interests lie in Sociology, Feminist studies, culture studies, and finding a potter's wheel she can convince her family to buy for her.