It is never a dull time to review and reiterate the need for a feminist reform, but there is all the more reason to do it at a time when more than half the population has hit a pause, and we have ample time in our hands to reflect upon how our society has been fashioned, as if by default, in male-centric ways. Despite some progress, the emerging global consensus is that, real change has been agonizingly slow for the majority of women and girls in the world. Today, not a single country can claim to have achieved gender equality. Multiple obstacles remain unchanged in law and in culture.

“There is still a widespread usage of patriarchal vocabulary in India, with respect to English as well as regional languages,” says Madhavi Menon, Director of Centre for Studies in Gender and Sexuality, Ashoka University. “It is interesting to note the nature of patriarchal usage of the English language, primarily because English is famously a non-gendered language: it has no genders for nouns, unlike Hindi, Urdu, and all Romance languages that derive from the Indo-European family of languages. So in its very make-up, English is not misogynistic,” she adds.

Foul language and cultural bias are what make the usage misogynistic. “Profanities seem to be sexist in all languages, which might well mean that they reflect the existing social and sexual hierarchies of the day,” Madhavi shares.

feminist language planning refers to the effort, often of political and grassroots movements, to change how language is used to gender people, activities and ideas on an individual and societal level.

To combat that, a movement called feminist language reform was conceived. Also known as feminist language planning, the reform refers to the effort, often of political and grassroots movements, to change how language is used to gender people, activities and ideas on an individual and societal level. This initiative has been adopted in countries such as Sweden, Switzerland and Australia, and has been tentatively linked to higher gender equality.

“Though there are no organised groups that actively work towards ungendering languages, some language activists directly work with identifying and changing sexist undertones and patriarchal vocabulary,” Madhavi further explains. Often referred to as linguistic disruption, and usually done to expose sexism in language, linguistic disruption means to break linguistic rules to expose a problem and make people aware of it. An example of this is the usage of the word ‘herstory’. The word now popularly refers to history which is not only about men.

Casual Sexism

“If you look for it, it is very hard not to find sexist undertones in language,” holds Shankari, a student. “In the case of Tamil, for instance, the language does not have equivalent female terms for Arinyan (scholar), Amaichar (minister), Vaittiyar (doctor). Because language is so intertwined with culture, language ends up unwittingly promoting male idolisation and gender profiling. Most Kollywood songs that top the charts are incredibly sexist, and objectify women,” she fumes.

“Language recapitulates gender hierarchies in our daily discourse in the form of sexist language. Such use of language contributes to an oppressive model of femaleness, with which women are assumed to identify, thereby perpetuating inequality,” says Hemanga Dutta, Sociolinguist and Assistant Professor, Centre for Linguistics and Contemporary English, EFLU.

In his paper titled, ‘Hyperonym, Femininity and Power dynamics: Evidence from Indian Language’, Dutta explores the gender inequalities and sexism inherent in Assamese and Malayalam.

“Female words in Assamese are often negative, powerless and indeed those words associated with women undergo a process of semantic derogation. Whereas, masculine terms function as superordinate terms which entail both males and females. As for example, uttar purux (next generation) can refer to both males and females although the etymological meaning of purux is male. In the same way deka xokti (youth power) embraces both boys and girls, but the Assamese meaning of deka in isolation is young boy,” Dutta shares.

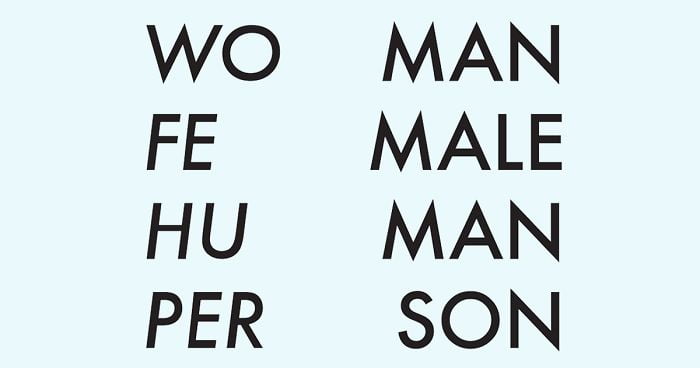

“The fact that masculine generics have been used for referring to sexindefinite referents can be indicated as a primary example of how language conceals women,” Madhavi points out. The use of ‘mankind’ and ‘He’ for God in English indicate the same.

Also read: Why Do We Need More Sensitivity For Mental Health Language?

The proverbs drawn from both these languages explicitly reflect upon the male dominance and subordination of females in the society of India. Feminist theorists attempt to reclaim and redefine women through re-structuring language. For example, feminist theorists have used the term “womyn” instead of “women” (non-standard spelling of ‘women’ adopted by some feminists in order to avoid the word ending -men).

There is no male counterpart for abusive words such as bonori, notesori, dehesori, kulota, xakhiniteja, poyeror murkhati, kulokhini, oxoti etc.

“There is no male counterpart for abusive words such as bonori, notesori, dehesori, kulota, xakhiniteja, poyeror murkhati, kulokhini, oxoti etc.,” Dutta shares. As an answer to this, some feminist theorists have reclaimed and redefined such words as ‘dyke’ and ‘bitch’. That is similar to the queer community repurposing the word ‘queer’, which used to be slur.

“Proverbs are the outcome of a sociocultural reality which provides a glimpse into the cultural ethos and behavioural patterns of the speech community. In Malayalam, there are countless proverbs that convey stereotyped images of women trivialising or denigrating them,” Dutta writes in his paper. One example could be the Malayalam proverb, “Pennu Petta Veedu Pole,” which translates to “Like a home where a baby girl has just been born.” This is used as a negative connotation, pointing at the disappointment of society at having a baby girl born into the family.

Agents of Change

The difficulty with a feminist language reform is that, chauvinist thinking has seeped into the smallest nooks of culture. To bring about any change requires a massive change in collective conscience.

“Many of us try individually to insist on gender-neutral language — on using chairperson and principal, for instance, rather than chairman and headmaster; on insisting that ‘he’ cannot be used as a universal pronoun. Criticising sexism in language is just one of the many battles one needs to fight on a daily basis in order to try — not necessarily to make the world a better place, but to make people in power become aware of their own status. We all need to think much more than we currently do,” Madhavi says.

Also read: The Violence Of Language: A Feminist Take On The ‘Culture’ Of Abuses

And it does seem like slowly but surely, people are beginning to think more and educate others. Student initiatives are especially successful in this regard. One such initiative is ‘The Un-Gendering Project’. “Feminism and gender equality are seen as taboo subjects, especially among the youth. We saw a dangerous trend where people started becoming blase about these discussions. We wanted to initiate conversations around gender in university spaces,” reads one of the Twitter posts of the initiative. @feminist, @lesbianherstoryarchives, @feministvoice and @feminist.herstory are some of the other famous online communities with a large following, that tackle a few facets of breaking down gendering in language.

Book sniffer, book lover and a silver tongued devil with a social hiccup, Radha is an epistemophile who lives by ‘Cogito Ergo Sum’. Slipping in archaic words into casual conversation her favourite hobby, her dream is to become a philosopher a 100th as good as Nietzsche. A student journalist from Chennai, Radha is all set to pursue MSc International Politics at SOAS, University of London coming September. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Featured Image Source: Bored Panda