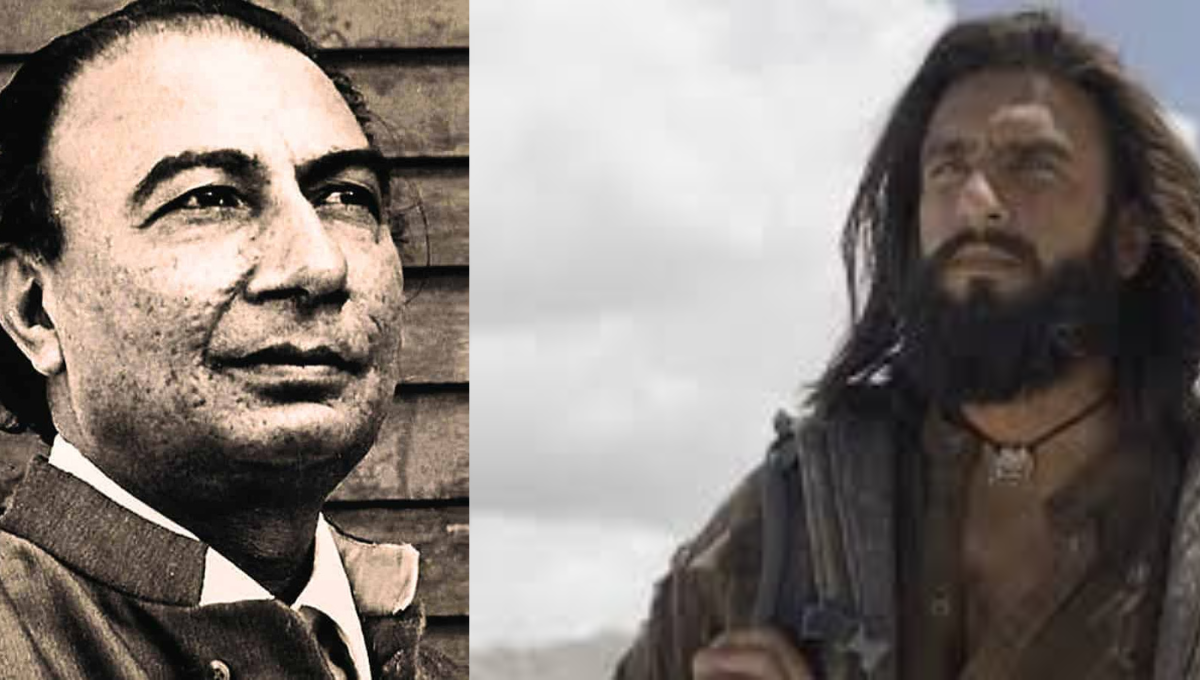

Aamis starts with the seeming promise of a classic love-story with unremarkable characters. Its uniqueness is derived from the age-gap between them, one’s marriage and child, and its transgression derived from the fact that the female character is the one who is older, married with child, employed and in control. Both protagonists are played by debutant actors- Lima Das plays Nirmali, a married pediatrician and Arghadeep Baruah plays Sumon, a PhD student studying food habits in north-eastern India. The film is set in Guwahati where they meet and connect over food, meat in particular, that Sumon is passionate about to the extent that he has a meat-eating club of friends.

Nirmali in the beginning of the film says, “Meat isn’t the problem, gluttony is,” in response to Sumon’s vegetarian friend writhing in pain because of over-eating meat. Sumon, a little later in the film, questions the idea of “normal” and its universality. The director, Bhaskar Hazarika, lays ground for questioning our senses of normal and eases the audience into the story with lighter challenges to society’s moral stances on food habits and relationships. Aamis depicts sad states of marriage where the husband is either unavailable or uninterested, and the wife is neglected, unwanted, and unsatisfied but is still bound. Nirmali shows how the bulk of physical and mental labour, both for the household and pertaining to the child is borne by the wife, even when she is working giving her a double work-day. Nirmali’s friend, Jumi, jovially makes one notice the lies needed to survive a dead relationship in a society that is scandalised by divorce, intimacy and anything swaying away from the conventional.

Aamis starts with more-or-less likeable characters who meet each other, their story smelling of early romance, excitement at receiving acceptance and attention, sudden changes and infections by each other’s moods, and desires of having more. In a society that punishes sexual relations outside of marriage and conditions people into having taboos for outlooks towards their sexuality, Hazarika gives carnal desires a much too literal rendition.

Aamis is not a regular romance or a psychological horror film; it not only defies genres but implants itself in the audience’s memory. The film offers much to think and debate about but not in a friendly-refresher-course-on-morality kind of a manner. It takes the ground of morality from under your feet and tosses it out the window, you watch it go but all you can do is get mixed up in this uncomfortable concoction of love, carnality and morality.

Knowingly or unknowingly, the protagonists hindered by popular social norms, find another way of sharing their flesh to the audience’s horrified disbelief. Makes you think about what love and deprivation can do, and also declares the seriousness with which Hazarika takes the task of challenging the normal. In the dictum of everything being fair in love and war, characters handle the forbidden love part while giving the rein to wage war against conventional morality to Hazarika. Audience is given the job of deciding whether this girl-meeting boy against many odds but ending up together, had anything resembling fairness.

Aamis talks about food and challenges the universality of normal but stays clear of controversies with plenty of mentions of people eating lizards and moths but no mention of the widely eaten beef and pork in the place that it is set in, Assam. One can argue about the feminist agendas of Aamis and our conditioned reactions to it. It presents its female characters in new and nuanced manners. It causes a subconscious distancing from them by making them unfaithful and ravenous. Nirmali is shown as sophisticated and sanitised, eating even human meat with cutlery.

Also read: Film Review: Thappad Is Not Just About A Slap, But About Its Male Entitlement

It is important to delve into the source of this distancing, whether it is the film that causes it or our patriarchal conditioning that is troubled seeing a woman having the upper hand in the power-play of carnality and relationships. She is the prime cannibal, while Sumon carries the female-exclusive burden of sacrificing for love as he limps and lovingly prepares elaborate dishes of his own flesh. The victim, if any, in Aamis seems to be Sumon who looks innocent throughout the film, from feeding Nirmali his own flesh without her knowledge to killing a human being.

The narrative of him being innocent is added to by making his body unable to accept Nirmali’s flesh, while the audience’s suspicion of her only grows with her hunger. There is an unrealised hypocrisy in Nirmali representing the gap between individuals’ ideals and their actions. This might make you reminiscent of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, but I’d say nah, no need to go there. Aamis at the outset declares her claim that meat is not the problem, gluttony is, then becomes about her becoming criminally ravenous.

The film is a strong commentary on people being enslaved by societal pressures because of a fear of ostracization. Both the characters are shocked, even disgusted when their friends inquire about physical intimacy between them. But their insidious way of sharing each other’s flesh does not vulgarise them. Because it is not typical and so they lack a conditioned response to it(?) Perhaps. It surely appears to them as less of a taboo than plain physical touch. When Jumi, Nirmali’s friend, gets pregnant from her extra-marital affair, we see relief dipped in an air of superiority from other lonely wives in Nirmali’s demeanour.

It is important to delve into the source of this distancing, whether it is the film that causes it or our patriarchal conditioning that is troubled seeing a woman having the upper hand in the power-play of carnality and relationships. She is the prime cannibal, while Sumon carries the female-exclusive burden of sacrificing for love as he limps and lovingly prepares elaborate dishes of his own flesh. T

When the protagonists are caught by the police and everything is out in the open, they hold hands, their first ever touch. Makes you wonder if it was singly the subconscious fear of public reaction stopping them from exploring in a more conventional and publicly graspable manner. The slow pace of Aamis suddenly changes towards the end, bringing the climax of making the matter public hurried. Quan Bay keeps the music of the film romantic for the most part, something that would correspond to ordinary early romance adding to the audience’s confusion of what to think and how to judge this jolt of a film. It takes a shady thriller tone briefly, as if testifying to its genre-defiance.

Aamis is not a regular romance or a psychological horror film; it not only defies genres but implants itself in the audience’s memory. The film offers much to think and debate about but not in a friendly-refresher-course-on-morality kind of a manner. It takes the ground of morality from under your feet and tosses it out the window, you watch it go but all you can do is get mixed up in this uncomfortable concoction of love, carnality and morality.

Also read: Film Review: Aani Maani, An Intimate Story Of Unlucky Identities

The film spares nobody, even philosophy enthusiasts in that it sends the Socratic paradox for a spin. The confident “I know that I don’t know” becomes a lost “I don’t know what to know”. Aamis gives so much food for thought that you will lose your appetite and sleep. It is less of a watch and more of a lingering experience. Hazarika has turned in an uncomfortable but necessary jolt to people’s ethical and aesthetic senses.

Featured Image Source: The Indian Express

About the author(s)

Sumaiya Taqdees is a content editor, and a post-graduate in Political Studies from JNU. With a penchant for art, a love for ironies, and an aspiration to become a tree, she is a person of few words except when writing.