Sightings

Sighting 1: Jamlo Madkam, a 12-year-old Adivasi girl was walking home to Chattisgarh from the chilli fields of Telangana. She walked 140 kilometres in three days and finally collapsed due to exhaustion, dehydration and muscle fatigue, 60 kilometres away from her home.

Sighting 2: A news video showed how a woman migrant gave birth on the road before continuing her long, seemingly endless march home after just a few hours of rest.

Sighting 3: Women, children and men sat squatted with their heads bowed in a big group outside a bus station as masked figures in white PPE suits sprayed bleach solution used to disinfect surfaces at these migrants on their way home from New Delhi to Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh.

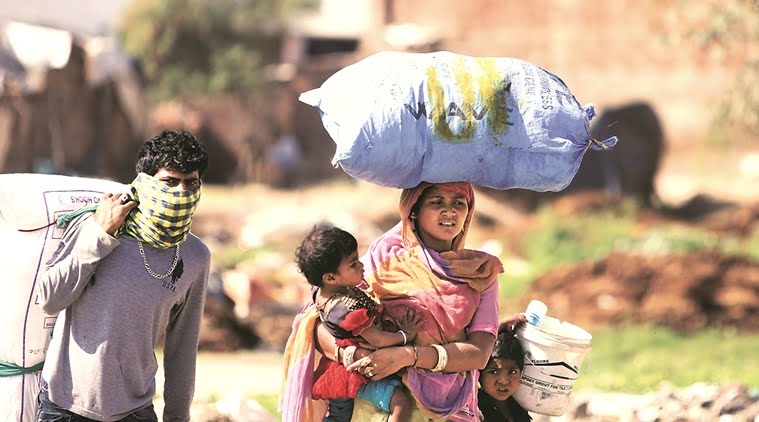

Sighting 4: A television journalist posted a video clip of a long line of migrants walking home at night somewhere outside Delhi on her Twitter account. In rhythmic unison, they loomed out of the dark into the camera light and back in to the dark. I begin to count the number of women in the group. In salwar-kameez and rubber chappals, with large, heavy canvas bags balanced on their head, they walked steadily past the camera without even a sideways glance.

Sighting 5: Another migrant woman made news when she was spotted dragging a large wheeled suitcase down the national highway with an exhausted toddler sleeping on top of it. On her way home in Madhya Pradesh, she looked reluctant to be filmed or to talk, so a man speaks for her.

Sighting 6: Thousands of migrant workers gather in a 70-acre saltpan in Vasai in the hope of catching the next Shramik train home. Their numbers include women and children. At the end of the day, the police drive and beat the migrants away even though all are now homeless. They come again the next day. The site boasts one mobile toilet. Where do the women and girl children go to relieve themselves? To a nearby stream, according to Kusum Gupta, aged 30. There are safety concerns but “what can we do?” she asks. The next day, Virottama Surendranath Shukla, a 58 year old woman standing in the long line to register for a Shramik train from the Vasai station collapses and dies under the blazing sun. All we know is that she was in her late fifties and had a preexisting medical condition.

The Vasai saltpan site boasts of one mobile toilet. Where do the women and girl children go to relieve themselves? To a nearby stream, according to Kusum Gupta, aged 30. There are safety concerns but “what can we do?” she asks.

Sighting 7: 35-year-old Avreena Khatoon collapses and dies while traveling from Ahmedabad to Katihar on a Shramik train via Muzaffarpur ordeal without adequate food and water. A video of her infant child attempting to play with her covered corpse on the railway station goes viral. A TimesNow report somehow deems it necessary to also include a statement by the railway police that the woman was purportedly mentally unstable.[7]

Sighting 8: 15-year-old Jyoti Kumari cycles 745 km from Gurgaon, Haryana to Darbhanga, Bihar with her injured father on the cycle carrier. Instead of acknowledging the abysmal failure of administration and governance that could have stopped this from happening, most news reports cited Ivanka Trump, the union sports minister, and the President of the Cycling Federation of India lauding the ‘cycle girl’, thus changing the narrative entirely.

Sighting 9: Two Santhali-speaking migrant women from Jharkand were trafficked into bonded labour in an incense factory outside Bengaluru. For over a year, they were illegally confined with their young children and one of them is raped as punishment for trying to escape. A chance encounter with another Santhali-speaking migrant man during the pandemic eventually leads to their rescue by local activists manning a migrant workers helpline. The report barely manages to make it to the mainstream news.

Also read: Covid-19 Pandemic & The Socio-Economic & Political Impact On Women

Seen, Yet Unseen

There was no shortage of news reporting on migrant workers on the road. Media discourse called it the great Indian migrant worker exodus. On a seemingly endless journey mostly on foot, pushed by hunger, unemployment and homelessness and the hope that a home is waiting for them at the end of it, news reports reported the unfortunate deaths of some of these migrant workers. While much is made of the manner in which they died, their names and other details as to what did they do for a living are often skipped. Thus, homogenizing and invisibilizing an entire population of essential service providers and workers. Needless to say, migrant women workers belong to the even lower echelons when it comes to the visibility of their trauma.

At the time of writing, I could only find the names of the Gond Adivasi male migrant labourers killed while sleeping on the railroad tracks in an article published by PARI which reprinted them from the Marathi publication Lokmat.

Amidst this masculinist discourse of endurance and suffering, the power and resilience of migrant women appears to remains unworthy of noting if not for the anomaly of Jyoti Kumari.

Amidst this masculinist discourse of endurance and suffering, the power and resilience of migrant women appears to remains unworthy of noting if not for the anomaly of Jyoti Kumari, which was then appropriated into an entirely different ’empowerment’ narrative. Women and girls have a similar role throughout these reports – carrying younger children and luggage. These women have walked the same distances and survived the same-yet-different indignities, humiliations and brutalities at the hands of police, bureaucrats and fellow citizens. The lack of hygiene and sanitation, hungry children and toddlers latching on to their exhausted bodies – become a problem of higher magnitude for women migrant workers on the road than men. To be a woman who embarked on a journey back home on one of those 40 ‘lost’ Shramik trains where the toilets must not have been cleaned for over 24 hours, is beyond many of our imagination.

Yet, most narratives include depicting women as the sacrificial mothers and a glorification of their strength against insurmountable pain.

Shown below is a sample of the pictures that would crop up on Google search results when one types “Indian migrant women workers affected by COVID-19”

What is happening to the women migrants on the road and during the pandemic? Answers to this question are not readily available. They have to be sought after, gleaned from reading between the lines of news reports shaped by the male gaze and I am not referring to the sex or gender of individual journalists here. Middle-class, urban bias in Indian news media, particularly in mainstream English language media, has been well-documented.

This is not to say that gendered, classed and casteist silences and invisibilities are not just a result of the pandemic – it exists rampantly in the discourse that does not surround the pandemic as well. But in the face of the humanitarian crisis that the COVID-19 led to in India, these differences evidently show.

Enduring Invisibility

Migrant women workers as a whole remain in the shadows of the dominant official and popular discourse. Transnational professional migrant working women are invisible in official state discourses about the pravasi bharatiya (overseas or non-resident Indian). Oishi (2005) found that there was little official recognition or support for women migrants – professional (in ICT, engineering, medicine, nursing) as well as ‘low skilled’ (in domestic, service, or construction industries). In fact, there is a complete absence of a gender perspective in our labour laws (Mazumdar and Neetha 2020).

While women workers in the organised sectors have some basic rights at least on paper, female-intensive work in the unorganised sector remains unregulated by labour laws. For example, most paid domestic work is performed mostly by migrant women. (Mazumdar and Neetha 2020).

Furthermore, migrant labourers are predominantly from dispossessed and impoverished Dalit, Adivasi and Muslim communities from the most economically backward regions in the country and across the border in Nepal and Bangladesh (Samaddar 2020). They are more concentrated in short-term and circular migration and perform dangerous and exploitative work alongside men on farms, construction sites, brick kilns, textile and other small factory units. However, they are typically paid far less and rarely on time in these sectors (Dutta 2019). Priyadarshini and Chaudhury (2020) remind us that women workers are usually the first to be told not to come to work unless called and are more likely to become victims of trafficking, sexual harassment and violence from contractors, supervisors and employers (Mazumdar, Neetha et al. 2013; Krishnan 2020).

Finally, the research tells us that ‘returning home’ is a gendered experience – men are welcomed but women, particularly young women are viewed with suspicion because of patriarchy and caste-based oppressive codes of honour (Priyadarshini and Chaudry 2020).

Also read: COVID-19 In India: The Shunned & The Forgotten Migrant Workers

At the time of writing, there was just one published study I came across as looking at the migrant workers’ concerns through an explicit gender lens. A team of activists affiliated with Karnataka Janashakti surveyed 1500 migrant labourers across the state. Respondents included a total of 284 women labourers, sex workers, transgendered peoples and devadasis. More than sixty percent of this group reported that they were unable to access any treatment for the routine ailments that accompany their occupations, predominantly sex work and begging. They shared their worries about not being able to get adequate quantities of food. Furthermore, the lack of income had jeopardised their children’s education since this is the time for school admissions, payment of fees and purchase of textbooks and uniforms.

Already Forgotten

Already the public gaze is turning away from migrant workers on the road to Unlock 1.0, upcoming elections and sports events. The new corona flashpoints and hotspots are a safe distance away in whatever we imagine to be ‘rural India’. The migrant workers represented an inconvenient but temporary anomaly in what was supposed to look like a well-planned strategy for disease management. There is now far less news about what is happening to them when they return home other than the regular reports about illness and death in state quarantine centers.

If the public gaze was easily (mis)directed, the sarkari gaze on the other hand, had deliberately ignored the plight of migrant workers for most of the lockdown. The recent AtmaNirbhar Bharat Abhiyan economic package offers neither immediate relief nor support for rural India where most live in precarious conditions, including small farmers, agricultural labourers, pensioners, disabled, and widows. This is a very different meaning of self-reliance than understood by Jyotiba Phule, Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar or Mahatma Gandhi.

References

Karnataka Jan Shakti. 2020. “”

Krishnan, Kavita. 2020. Fearless Freedoms. New Delhi: Penguin.

Mazumdar, Indrani, and Neetha, N. 2020. Crossroads and boundaries: Labour migration, trafficking and gender. Economic and Political Weekly 55(20). Retrieved from https://www.epw.in/journal/2020/20/review-womens-studies/crossroads-and-boundaries.html

Mazumdar, Indrani, Neetha, N. and Agnihotri, Indu. 2013. “”

Oishi, Nina. 2005. Women in Motion: Globalisation, State Policies, and Labour Migration in Asia. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Pande, Mrinal. 2011. The Other Country: Dispatches from the Mofussil. Penguin Books.

Priyadarshini, Anamika and Chaudhury, Sonamani. 2020. The return of Bihari migrants after the Covid19 Lockdown. In Samaddar, Ranabir. (ed.). Borders of an Epidemic: Covid-19 and Migrant Workers. Kolkata: Calcutta Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.mcrg.ac.in/RLS_Migration_2020/COVID-19.pdf

Nisha Thapliyal is Senior Lecturer in the School of Education at the University of Newcastle, Australia. She studies and teaches about comparative education, critical pedagogies, gender and development, social movements and activist media. You can find her on Twitter.

Featured Image Source: Huffington Post