A photograph is said to convey what a thousand words can’t. It is not a replica of reality but rather a frozen moment which memorialises time. It plays with our memory and lets our imagination flow limitlessly. It shows us what is right in front of us. We are forced to look closer and search for the fizzling stories hidden in the fringes. A photograph can conjure up emotions and thoughts through negative spaces and produce art from mere being. It weaves a narrative through the eyes of the photographer. It’s not always possible to understand a person’s point of view. Still, the way Avani Rai uses photography makes it impossible to miss.

Well-known for her documentary on her father Raghu Rai, renowned photojournalist, a lot of her work is based in Kashmir. She is quoted saying, “In Kashmir, everything is a canvas. Whether you are standing and there is a reflection, or a child sitting in front of you, or a security person in a bunker; everything tells a story.” She uses her lens to paint fragments of daily life amid chaos and conflict. With the recent abrogation of Article 370, there were heated debates and arguments about different political facets. But only through her series Exhibit A, can we truly see the human cost of generational trauma. Her series is aimed to shift the focus to the lost voice of Kashmiri people, especially women and children. Here are a few pictures from Rai’s Instagram and her photography exhibits, that portrays the humans in Kashmir who are trapped in an endless siege.

This picture of a classroom in Kashmir shows us just how bleak everyday life is in the valley.

A classroom is usually a colourful space with the youth looking forward to their boundless future of hopes and dreams. However, here we see how far from ‘normalcy’ the lives of these children are. More than the lack of facilities, Avani Rai has captured the feeling of being trapped in limbo by making us see the scene through bars, reminding us of a life of imprisonment.

Image of women protesting from 27th September 2019 amid a communication blockade by the Indian government in the valley.

It’s a powerful image of protest and dissent by women. Media coverage of news in the valley is mostly of violence and bloodshed. This shows another side to it, which is often ignored by all parties discussing the issue: the human side. It shows real people whose lives have been paused endlessly to an extent where the pause is the only thing they know. Their voices have been silenced. The conflict has been nationalised to a point where it is no longer about the people from the region itself. The photograph is thus profoundly meaningful in showing that the civilians in Kashmir have an opinion. But they’re rarely ever asked for it.

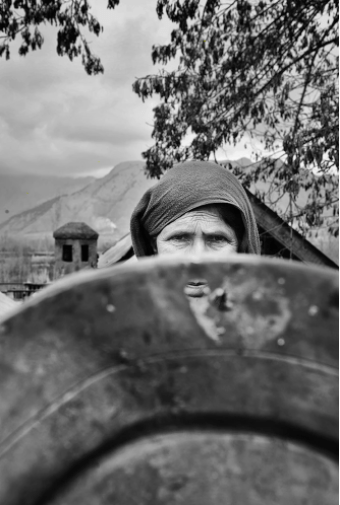

Photograph of a woman looking through a plate with a bullet hole, damaged by the Security Forces in 2018.

A plate is one of the most mundane objects in everyday life; violence as a subject has been superimposed onto that as well. The ordinary and extraordinary are woven together so seamlessly that there is no distinction. It portrays the epistemic quality of violence where it’s not just about the physical acts. There is a longer impact that it has on the minds of people because of how common it is. The knowledge of un-safety lurks around every moment making ‘normalcy’ an aspired, desired and utopian category.

Picture of children making gun gestures at bullet holes on the wall in the encounter site of Lateef Tiger, pro-Pakistani outfit Hizbul Mujahideen’s militant.

He was gunned down by the Indian Security forces in May 2019. Avani Rai is quoted telling Vice, “When I picked up my camera to take their photos, these boys lifted their hands and made gun gestures at the bullet holes in the wall. What do you think they will grow up to be?” It paints a picture of epistemic, psychological and social violence the children face regularly.

Also read: Unpacking The Siege: Has Normalcy In Kashmir Been Restored?

Photo from Rai’s Instagram which she had captioned ‘Little women from the last village in the India Pakistan border, Ladakh.

The monochrome adds an element of bleakness and makes us focus on the little girls’ expression and emotions. Their faces look tired, no one is smiling. What this does is show us the human element of the conflict, the cost in terms of women and children’s lives. Indian or international media is not allowed to freely cover the issues going on in the valley. Years from now, collective memory-making processes may very well erase these individual narratives. Rai’s photographs act as markers of stories untold, trauma unspoken and lives shattered.

However, Rai has found herself in the middle of a controversy more than once. In October 2019, the high-end fashion label Raw Mango released a series called ‘Zooni‘ which features a woman in a pheran. It was called out for exotifying the Kashmiri woman at a time when the Valley was in a complete lockdown. Rai and the brand were criticised for monetising a region which garnered international attention due to the numerous human rights violations. For a photographer who claimed to stand for the Kashmiri people, this was not an accurate representation of reality. Rai, however, clarified that she had expressed her disapproval at the timing but she was contract-bound.

Furthermore, in December 2019, the online publication Brown Paperbag displayed Rai’s photography in their pop up story. The invite email read, “We’re exhibiting photographer Avani Rai’s gorgeous photographs of Kashmir under lockdown at our One Amazing Thing pop up store at at Kala Ghoda, where you can also get your hands on what is quite possibly the best chocolate tart in the city.” It was criticised severely for romanticising and normalising the humanitarian crisis. Both Rai and BPG offered an official apology. She stated that her work on Kashmir would never be on sale. Further, she clarified that she is only committed to shed light on the atrocities committed there through her photography.

Also read: An Enduring Conflict, The Homeless And Women In Kashmir

“While men are the direct targets of violence; the trauma for women and children is of no less a magnitude. They are vulnerable. Through this project, I tried to explore the ordinariness of daily life of both women and children seemingly forgotten. What are their means of survival in the conflict that has surrounded them for decades now? This has become a very poignant question for me,” she says in an interview with The Asian Age paper.

The photographs in the series are sans colour because Avani Rai believes that the human sentiment captured does more than colour can ever do, and the spotlight is on the multitude of expressions. Her work humanises the happenings in Kashmir and shows the viewer that there is no version of normalcy there; that the only daily life that exists is strewn with violence, trauma and conflict.

References

Featured Image Source: The Indian Express