Editor’s Note: This month, that is July 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Feminism And Body Image, where we invite various articles about the diverse range of experiences which we often confront, with respect to our bodies in private or public spaces, or both. If you’d like to share your article, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

When my professor mentioned that the students were expected to maintain a “professional dress code” for the online classes, I scoffed. After all, how could she possibly guess that I was wearing the pizza print shorts from the night before, instead of the full-length leggings that I would normally wear? I felt like a rebel—a student who was openly flouting the college rules. You see, as a student of a prominent, “progressive” South Bombay college, I had to adhere to the strict dress code that our college imposed—no sleeveless clothing, no ripped jeans, only ankle length bottoms, and so on. After being a part of the institution for the past 4 years, I, like several of my peers, joked about the dress code. It bothered us, but not to a great extent. You just needed to get used to it.

Yet, when I pondered over the concept of the dress code, I realized how it extended beyond the threshold of the institutions it was imposed in. Dress codes socialized us into gender roles, affected how we negotiated with our bodies, attached morality to clothing and justified rape culture.

My long-lasting affair with dress codes in educational institutions began in kindergarten itself. As a co-ed convent school student, I had to strictly adhere to the uniform that was set by the administration—a beige frock, with a red belt, matching red rubber bands/ribbons/headbands and brown canvas shoes. By virtue of having donned this uniform for 12 years, I can attest to the fact that these garments were neither fashionable nor functional. Very early on, we realized the underlying theme of the uniform—cover up! The hem of the frock had to extend beyond the knee, the uniform had to be fitting but not “too fitting”, our hair had to be tightly wound and so on. The punishment for violating this dress code was an official remark in our handbooks for ‘deviant’ behaviour.

My long-lasting affair with dress codes in educational institutions began in kindergarten itself. As a co-ed convent school student, I had to strictly adhere to the uniform that was set by the administration—a beige frock, with a red belt, matching red rubber bands/ribbons/headbands and brown canvas shoes. By virtue of having donned this uniform for 12 years, I can attest to the fact that these garments were neither fashionable nor functional.

These punishments, or formal negative sanctions ensured that the dress code was followed inside the institution. Informal negative sanctions worked wonders too—being at the receiving end of dirty looks, comments targeted towards our character, et cetera made certain that the dress code was followed beyond the institution. As a female student in her formative years, who was reprimanded for wearing a uniform that was an inch above the knee, or for having a broken top button, the idea of one’s clothing was very closely interlinked with one’s morals/character. The constant reinforcement of clothing and character as synonymous was ingrained in our minds, which resulted not only in us following the dress code later in life; but also making value judgments about women who didn’t. Clothes began to symbolize values—women who wore miniskirts were ‘easy’, those who wore low cut tops were ‘attention seeking’ and so on.

Furthermore, the means by which the adherence to the dress code was checked often violated the student’s privacy. For example, in a friend’s school, teachers would “verify” that female students were wearing tights under their uniforms by pulling up their frocks in the assembly. The lesson? Follow the dress code or endure being berated publicly.

What’s more, female students who were more voluptuous, were victims to this policing more often. In my personal experience, I was questioned about the functionality of my brazier by a teacher, because my breasts were “moving” when I was running. Another friend was instructed to wear longer shorts during a sports game, because she was a ‘healthier’ girl. These instances of sexualising and policing young female bodies under the pretense of rules affected how we viewed our bodies. We began to self-censor our activities—we would avoid jumping, or walk slower, so that our breasts wouldn’t move as much. Our bodies felt inappropriate, dirty.

The constant reinforcement of clothing and character as synonymous was ingrained in our minds, which resulted not only in us following the dress code later in life; but also making value judgments about women who didn’t. Clothes began to symbolize values—women who wore miniskirts were ‘easy’, those who wore low cut tops were ‘attention seeking’ and so on.

The dress code also dictated what activities we participated in, especially when it came to sports. During the selections for the official school team for the inter-school kabaddi match, we didn’t have enough female students to conduct selections for the under 17 team. This was because the female students from 8th, 9th and 10th grade who formed the team didn’t want to wear shorts and a jersey, as it wasn’t “appropriate” clothing. As a result, the under-17 team largely consisted of female students from lower classes. Even then, our coach made it a point to announce that the under-14 boys’ team was better than the under-17 girls’ team, because “boys were naturally better at sports.” Obviously, skilled female players not participating for fear of being shamed for wearing sports clothes wasn’t a relevant criterion.

This gendered approach to the dress code was visible from the get-go. Firstly, in terms of how the uniforms were designed, but also in context to how the penalties for violating the dress codes were imposed. The male students in my school had to wear a beige shirt and shorts (which were above the knee) till 8th grade, and beige pants after.

Also read: Why Do School Dress Codes End Up Sexualising Young Girls?

As students who had physical training each week, the boys’s uniforms were far more functional. Moreover, they didn’t seem to be held to the same standards of “covering up.” The violations of the dress code by male students weren’t viewed to be as serious either. In contrast, several peers, as well as I have been asked to exit a class, “fix” our uniform, and then re-enter. Plainly put, a dress code violation by a female student was an issue of greater importance than their education.

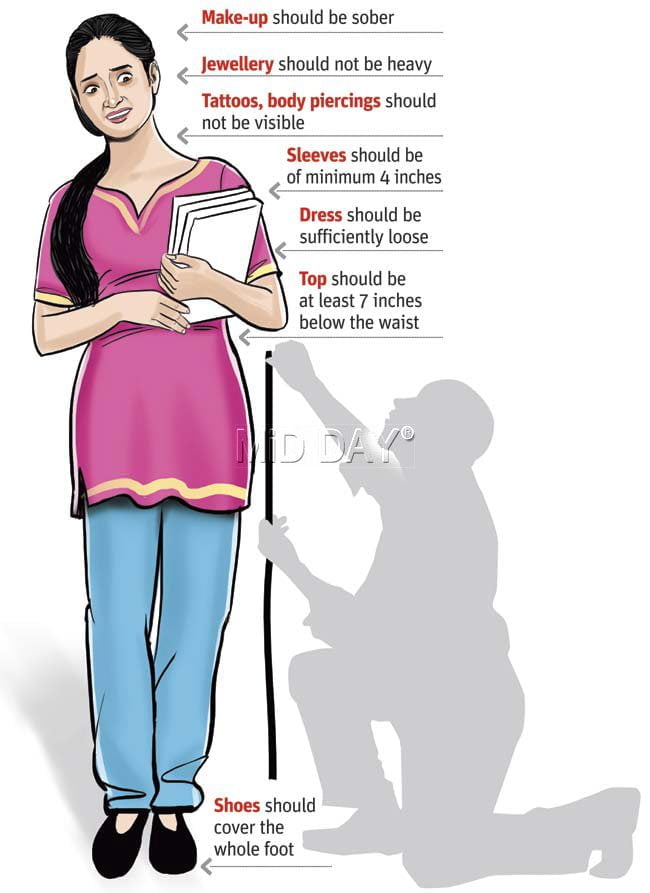

Fast forward to college, and not much had changed. While the students were exempt from wearing uniforms, there was still a dress code that decided what was appropriate and what wasn’t. Monetary fines replaced official remarks as negative sanctions for violating the dress code. This meant that students had to actively buy/wear clothes that fulfilled the requirements set by the college dress code to avoid monetary loss. Since most of the students spent a minimum of 5-7 hours in college for 6 days a week, this dress code would be extended and normalised for many, as the dress code for their lives outside of campus as well.

As students who had physical training each week, the boys’s uniforms were far more functional. Moreover, they didn’t seem to be held to the same standards of “covering up.” The violations of the dress code by male students weren’t viewed to be as serious either. In contrast, several peers, as well as I have been asked to exit a class, “fix” our uniform, and then re-enter. Plainly put, a dress code violation by a female student was an issue of greater importance than their education.

When discussing the dress code in educational institutions, it is also essential to analyse the reason that is often cited for imposing it—safety. And while this may seem like a sensible justification, it is not free of faults. Firstly, “safety” being the reason for having a dress code, implies that the clothing that one wears determines whether the person is safe or not. This approach places the onus of an assault on the victim, instead of holding the abuser/assaulter accountable. It justifies sexualising females and propagates rape culture to young, impressionable students.

Secondly, it’s the easy way out on the part of the institutions, as it places the emphasis on the individual’s clothing, rather than providing comprehensive education about sex, good touch, bad touch, how to defend oneself et cetera.

Lastly, educational institutes are supposed to be safe spaces for the students. Yet, these dress codes are imposed within the educational institution’s campus. Surely then, one must question why students need to guard their safety in these spaces? If students aren’t safe in their schools, and colleges, then where are they safe?

Also read: Students Rise Against St Francis Degree College’s Sexist Dress Code

As the author Merlyn Gabriel Miller states, “Schoolgirls are not distractions. They are students. Teach them something other than misogyny.” Sexism cannot continue to be imposed under the garb of dress codes. On the part of the educational institutions, there is a need for discourse about why the dress code is necessary. There must be discussion about how a gender–neutral, functional approach can be incorporated. An evaluation of the dress code is long due.

Priyanka Joshi is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology and Anthropology from St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai. She’s an intersectional feminist and her interests include writing, reading, cooking; or at least trying to. You can find her on Instagram and LinkedIn.

Featured Image Source: George State Signal