Throughout history, the precarious position of widows has been well known. Especially among the upper caste Hindus, widowhood meant subjection to various orthodoxies and exploitation throughout their lives. One such practice associated with widowhood, that has been immensely debated and contested on grounds of culture and systematic oppression is the system of sati.

‘Satipratha’: A Historical Background

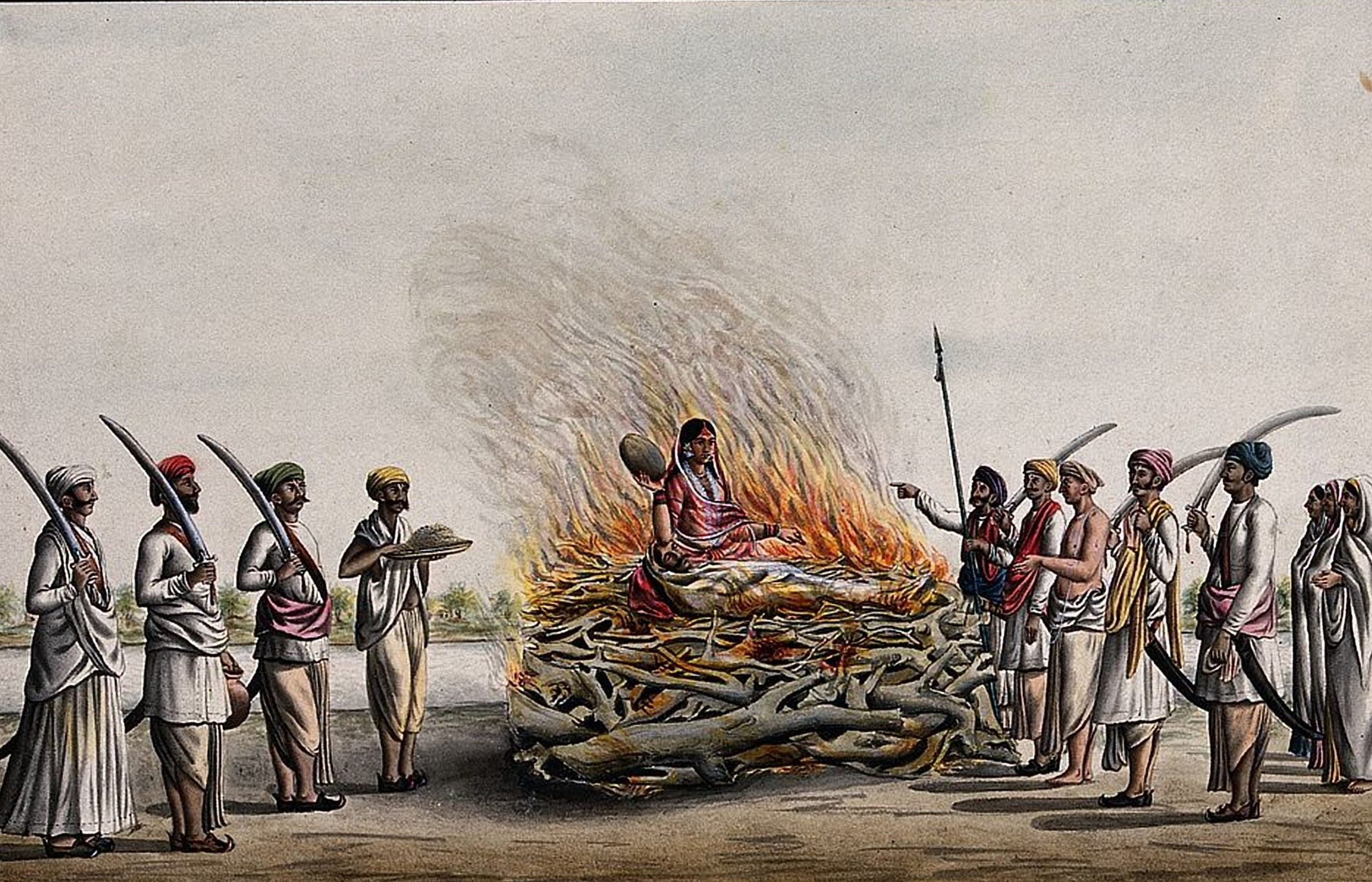

The practice of sati (widow burning) has been widespread in India since the reign of the Gupta Empire. The practice of sati as is known today was first recorded in 510 CCE in an ancient city in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Over time, this practice became widespread in northern and central India and especially among the Rajput, in the state of Rajasthan. The term ‘Sati’ also often referred to as ‘suttee’, translates to a “chaste woman” in Hindi and Sanskrit texts. Another commonly used term is ‘Satipratha’ which signified the custom of burning widows alive. This custom was definitive of Hindu tradition for a very long time. Women were indoctrinated to believe that their destiny lay in committing their lives to their husbands even after death.

These cultural beliefs around this practice were aggressively supported and propagated by fundamentalist religious groups and locals alike, and thus became an important source for reinforcing oppressive customs against Hindu widows. However, opposition to this act was equally strong and the practice was highly criticised for its atrocious and oppressive character. It was only in the year 1829 that sati was legally abolished by the Bengal Provincial Government through the joint efforts of Raja Ram Mohan Roy and William Bentinck, the then Governor General of India.

The need for social and religious reform manifested as a result of coming in contact with western culture and education that created a new awakening amongst the social reformers of 19th century India. Although the status of woman continued to be derogatory and exclusionary, the new educated intelligentsia like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar started advocating for women’s rights and abolition of social evils like ‘Sati’ and ‘child marriage’. Following this Act, there were various other laws that followed, condemning and criminalising this practice; yet till date the evils of this tradition continue to reign, unrecorded.

These cultural beliefs around this practice were aggressively supported and propagated by fundamentalist religious groups and locals alike, and thus became an important source for reinforcing oppressive customs against Hindu widows. However, opposition to this act was equally strong and the practice was highly criticised for its atrocious and oppressive character.

The Immolation of Roop Kanwar

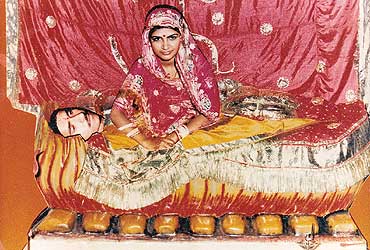

One such incident of sati that has garnered immense attention and spurred a new chain of debates and movements was the case of Roop Kanwar—the last known case of sati in India. On September 4, 1987 Roop Kanwar, an eighteen-year old teen had taken the decision to jump into the funeral pyre of her husband in an act of self- immolation that came to establish a legacy that would live on for years to come. The mass audience who were spectators to this act, described it as a voluntary action. This incident had jolted the state of Rajasthan and spurred a huge human rights campaign countrywide.

What was an act of will created a lot of uncertainty and chaos. Within only eight months of marriage, Roop Kanwar became a widow. Her decision to perform sati was upheld with high honour by her relatives and the locals alike. However, her parents only came to know about the death of her husband and her decision to perform sati in the morning newspaper. Although such cases of sati have been recorded prior to this case, but what made the difference following Roop Kanwar’s incident was the huge outcry of various women’s movements and the political aura surrounding the incident, that turned it into a battle between religious and cultural orthodoxy on the one hand, and the assertion of women’s rights on the other.

Sati as a Metaphor for National Identity

Roop Kanwar’s death was symbolic in various ways. Although a widow, she was adorned with ornaments and the traditional red attire of a Hindu bride. There have been various pictures depicting her moments before her death, where her husband lay in her lap and she is portrayed as a mother cradling her son.

What do these visuals entail?

Roop Kanwar has been depicted as the ideal of womanhood which is also closely related to ideas of Hindu nationalism. Since the beginning, Hindu nationalists have sought to establish the symbols of the nation often along the lines of a motherly figure. What the idea of ‘mother earth’ represents is not merely a form of devotion towards motherhood but a very gendered notion of nationalist sentiment that consolidates itself on the idea that a woman is someone to be controlled and protected.

In various contexts, nationalist discourses are built around women’s bodies as the symbol of national honour, which if violated can bring dishonour and shame to the nation. The custom of sati reflects this very idea. The young widow needs to be tamed and her sexual desires controlled. Therefore, to maintain her chastity the only way that remains is to burn her alive, which is why the state laws criminalising the act and banning the construction of a monument at the site of the funeral, was met with huge protests by locals and religious groups who called it as an intervention in their cultural beliefs and practices.

The huge audience who attended the ritual often describe it in divine terms, hailing her decision, at a time when this practice has already been banned by law. Even today, after thirty-three years since the incident, people continue to revere her and the funeral site where a makeshift shrine has been constructed in her memory. A ‘chunri ceremony’ was held, 13 days after the incident with festivities, amidst a lot of apprehensions and in violation of court orders, where people took out on the streets of Deorala in a moment of glorification, one which is symbolic of brothers walking the bride in the traditional Hindu wedding ceremony.

On October 1,1987, the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Bill was introduced that made abetment to committing sati or its glorification punishable by law. It was passed in both Houses of the Parliament and received Presidential assent on January 3, 1988 and came into effect on March 21, 1988. Of all the 45 accused in relation to abetment to the act and its glorification, 25 have been acquitted, six accused have died during trial while another 6 have been absconding.

Even today, after thirty-three years since the incident, people continue to revere her and the funeral site where a makeshift shrine has been constructed in her memory. A ‘chunri ceremony’ was held, 13 days after the incident with festivities, amidst a lot of apprehensions and in violation of court orders, where people took out on the streets of Deorala in a moment of glorification, one which is symbolic of brothers walking the bride in the traditional Hindu wedding ceremony.

Also read: Both Rajkahini And Begum Jaan Tell Us That Women’s Honour Is…

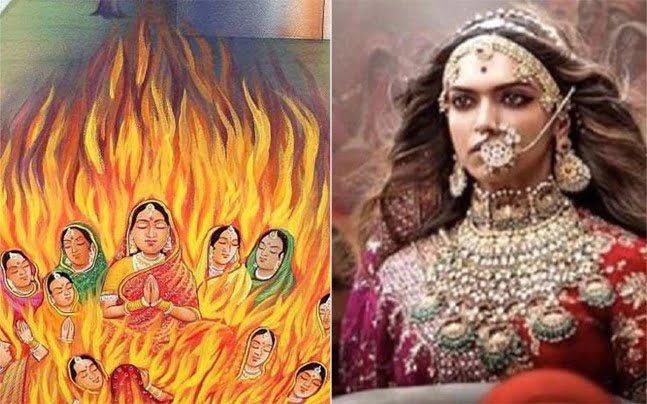

Jauhar: A Practice of Mass Immolation

A similar historical practice is the ‘Jauhar’. Although both historically prominent amongst the Rajputs, there exists significant differences between the two. While sati was an individual act of self-immolation Jauhar was more of a collective or mass suicide. Further, while sati may be performed by any women belonging to upper caste, Jauhar was performed by the royals as an act of escape from the atrocities of Islam or other invaders resulting from the defeat of their husband on the battlefield.

A very recent film that has been the subject of various debates and speculations is ‘Padmaavat’. A controversial Bollywood epic, this movie sparked off various protest movements across the nation, mostly by Hindu groups and Rajput caste organisations for allegedly portraying the Rajput queen in bad light. There have been other speculations regarding whether the film was really a historical reality or a piece of fiction.

The Question of Agency

In both the cases, the various protests by fundamental religious organisations reflect an incongruity of belief and rationality. There is an attempt to defend and glorify women’s right to kill themselves in the name of cultural belief. That it represents the valour of the Kshatriya caste groups is a common narrative constructed throughout these years. Further, the fact that it is an act that is committed voluntarily is still up for debate. There were various evidences to show that Roop Kanwar might have been sedated and even showed resistance that was not visible across the huge pile of fire and smoke that engulfed everything in sight.

What is upheld in the name of culture is an act of extreme violence. Even for incidents of sati that are cited as acts of will, it is necessary to understand why some women choose to go through this ordeal. It is not solely because of the wish to unite with their husbands after death, rather to escape the barbarity that they might be subjected to as a widow if they are alive. Vrindavan, Varanasi are the few places that widows are banished to and forced to resort to begging for the rest of their lives. Often subjected to sexual exploitation and other inhumane practices, they do not have any alternative but to commit suicide, which is glorified by the people as an act of will committed in the name of god.

There is an extreme patriarchal dimension surrounding the politics of sati. The symbols of the ideal woman and the metaphor of the goddess used to narrate these incidents have implications beyond the act itself. The ideas of consent and coercion are further issues that need to be understood within the larger systems of religious, economic and social oppression that these women are subjected to throughout their lives.

Also read: How Did Bollywood Allow Subversion? Comparing Padmavat And Mirch Masala

References

- Indian Express

- The History Behind ‘Sati’, A Banned Funeral Custom in India

- Thirty Two Years After Roop Kanwar’s Death, Blind Faith Still Overshadows Reason | Outlook India Magazine

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

A Sociology graduate with an interest in art and music. An enthusiastic reader especially concerning gender dynamics in mythological stories. A cat mom and an occasional photographer often found cafe hopping in Delhi.