Editor’s Note: This month, that is August 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Campus Experiences, where we invite various articles to highlight the diverse range of encounters we often confront when we are a part of any educational institution or space for learning be it schools, universities, colleges, tuitions and home. If you’d like to share your article, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

For a university situated in the capital of a nation that sells itself to globalization with the tagline ‘unity in diversity’—cultural, economic, and social diversity is always a good self-promotional point. However, if you have been in DU for even a semester, the rose-tinted lenses wear off soon enough. We may have students from all over the country and beyond, but our academic and cultural spaces have not learnt the rhetoric of respecting the history that comes with different family and socio-economic backgrounds.

A couple years in this space have made me question my personal notions—what kind of diversity do we have? And is the presence of diversity the same as accepting it, those who bring it to the University of Delhi (DU), with open arms?

An average day in an English literature classroom in a college considered prestigious and ‘intellectual’ like Lady Shri Ram College involves professors coming to class, throwing names of critics (mostly foreigners, usually white), and expecting students to have read them.

An academic space is meant to challenge you and to inform you of things you were formerly ignorant of, but the sighs of disappointment, ‘How do you call yourself educated’, and steely eyes filled with judgement when one is unaware of what the professor is speaking of—are all methods of shaming that do more damage than harbour a motivation to learn.

An academic space is meant to challenge you and to inform you of things you were formerly ignorant of, but the sighs of disappointment, ‘How do you call yourself educated’, and steely eyes filled with judgement when one is unaware of what the professor is speaking of—are all methods of shaming that do more damage than harbour a motivation to learn. The worst part, however, is not the fact that our academic spaces shame us when we do not know Judith Butler’s gender performativity ideas, or Marx’s socialism, or Nietzsche’s understanding of a ‘dead God’, but it is the sadness in realising that it is the role of our universities and teachers to make us learn of all this, and much more.

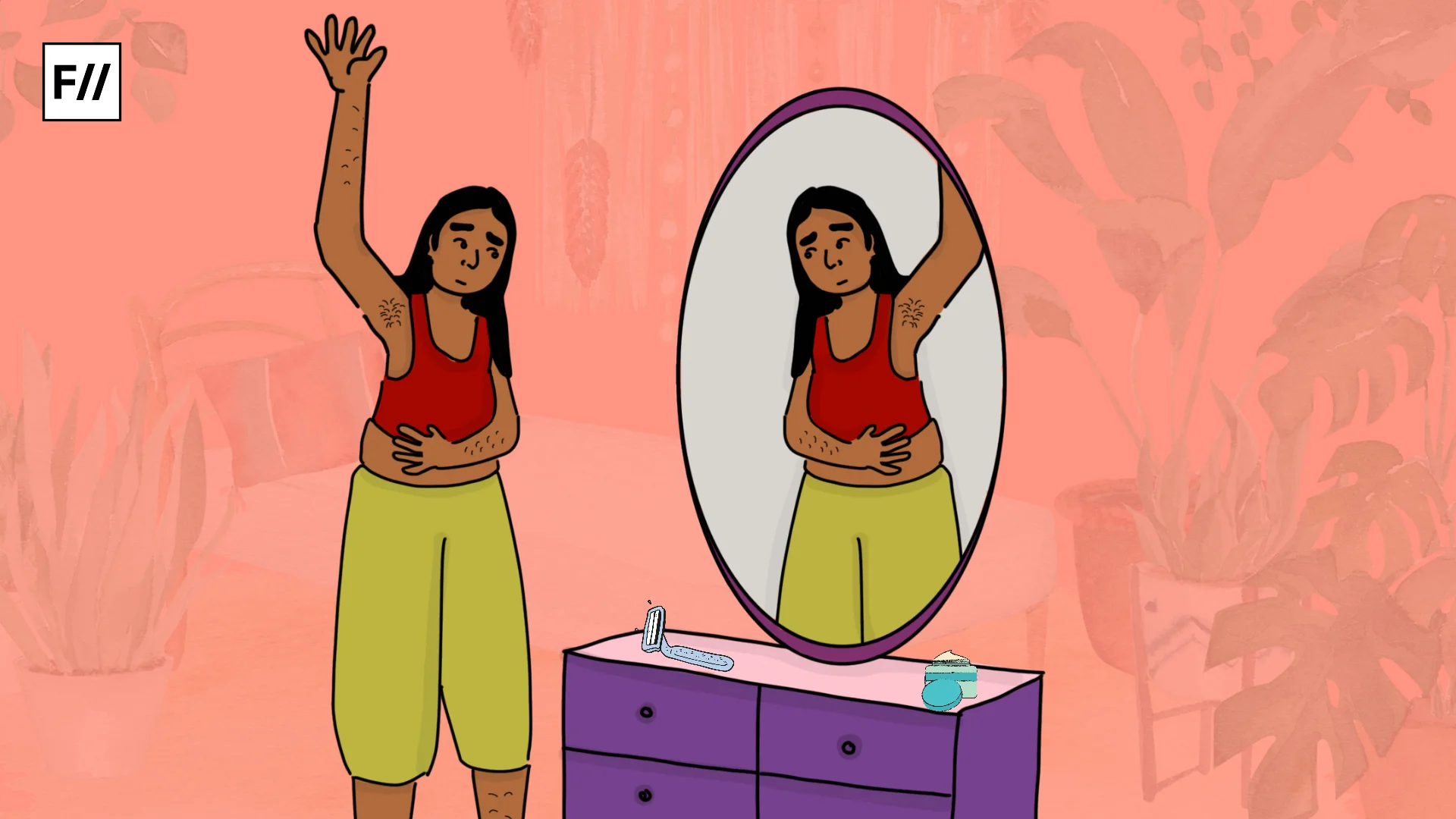

It is, if nothing, unfairly oblivious to only speak of professors and classrooms as the harbingers of this attitude, since our own friend circles and spaces play a horribly significant role in this process. We, as young adults stepping outside the comfort of our homes, seek a sense of self-worth and validation among our friends. When belittled for listening to a certain kind of music, or not having watched a comic’s Netflix special, or for not reading a book considered ‘high art’, it is inevitable to lose faith in our intellectual capabilities. To be told that you need to have done specific, mostly privileged and expensive, things in order to fit in is not only elitist but also a form of childish bullying that all of us can call a culprit to.

Also read: Dalit Women Learn Differently: Experiences In Educational Institutions

Most of us have not grown up with our fathers playing Vinyl records of Bob Dylan or The Beatles to us as kids. The tag of a Grammar Nazi (wrong on historical and cultural appropriation terms as well) that people—even I, at one point of time—wear as a badge of honour will never encourage somebody to learn better English, but will be a reminder of the inefficiencies in their background. It says something about their history, over which they did not have active control, but it defines you as a person—an elitist who does not wish to be kinder and more empathetic.

To recognise that there are conditionings different than your own is a significant aspect of mental maturity that DU colleges fail to instill in us. Challenging us academically or giving us a plethora of resources to learn from, is the thing one seeks, but DU’s rather popular culture of shaming us into learning is psychologically flawed and ethically problematic at a time when we are learning and unlearning the caste, class, and cultural privileges and meritocracy.

We, as young adults stepping outside the comfort of our homes, seek a sense of self-worth and validation among our friends. When belittled for listening to a certain kind of music, or not having watched a comic’s Netflix special, or for not reading a book considered ‘high art’, it is inevitable to lose faith in our intellectual capabilities. To be told that you need to have done specific, mostly privileged and expensive, things in order to fit in is not only elitist but also a form of childish bullying that all of us can call a culprit to.

It is true that DU is not the only place where the culture of shaming is prominent and propagated, but it is one of the prominent epicentres of education and politics in the country. Especially when the world is struggling with a global pandemic like COVID-19, the unilateral dictation of the decision to conduct online exams too falls in line with this structurally inept method of teaching-learning, wherein students are made to believe that vomiting answers on a sheet while the clock runs out is the only way of testing merit.

Image Source: DU Beat

This meritocratic ideal excludes the psychological, economic, social (caste and class), and perhaps the most important one in an era of diseases, physical limitations of young students. This move, in tandem with the culture of shaming, prevalent in DU circles, assumes accessibility for all and shapes a narrative of lack, deeply affecting the anxiety and self-esteem issues of students who are already struggling with the worst economic crisis and job market in over a 100 years since the War. It is not conducive of learning and assimilating knowledge, but pushes students to the brink of harrowing exhaustion.

Also read: Disability And The Need For An Inclusive Sex And Sexuality Education

To have diversity comes with the need to accept it, and I know our classrooms can change for the better. Arundhati Roy said, “To love. To be loved… To try and understand… And never, never to forget.” (If you have not read her, it’s okay. Take this as my recommendation, if you were looking for one?) I hope DU does not forget its role and duty to diversity—intellectual and of all kinds—and understands that we are all learning, and we can do with a little kindness.

Anushree is a literature student at Lady Shri Ram College, teller of stories, learner of feminism and a supporter of petting dogs. You can find her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Featured Image Source: The Print

This is an interesting read on privilege in India, and the many ways it manifests. Do you think that the ‘shaming’ is deliberate, or an unconscious gesture on the professors’ side, to make themselves seem better and more “well-read”?