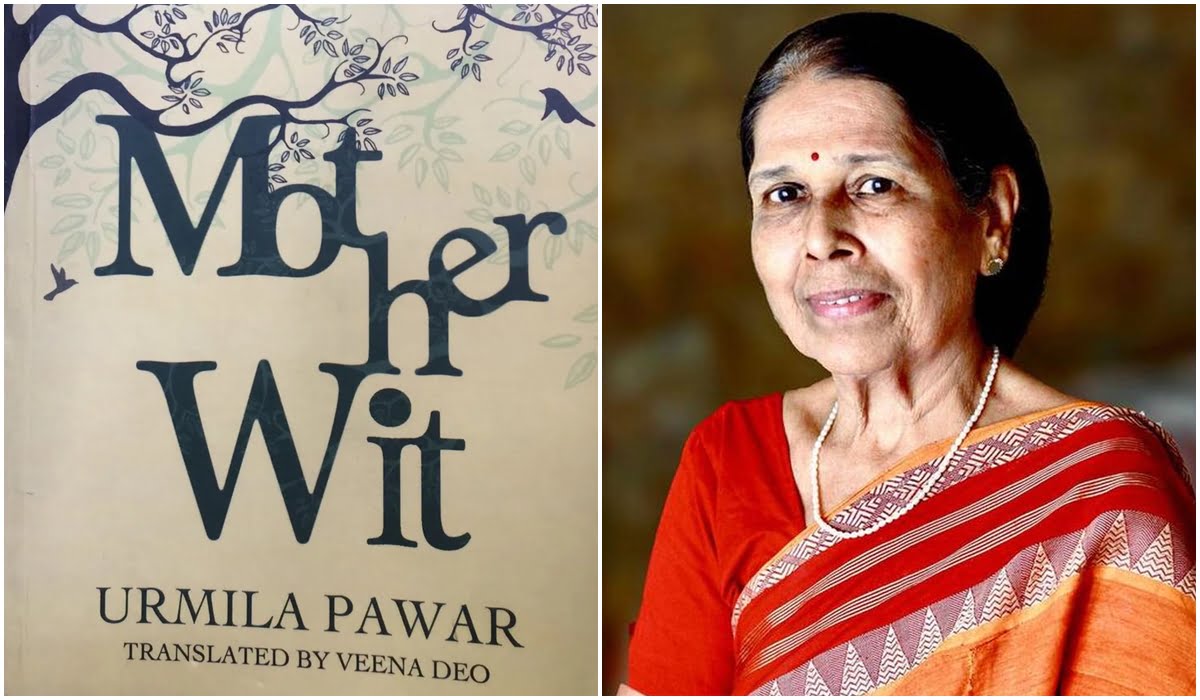

India, in its early days of independence, was even more caste rigid than it is today. It refused to accept and identify the social hierarchy that existed in favour of the Brahminical hegemony. Urmila Pawar, born two years prior to 1947, has been a witness to the said society from the early days of India’s conception as a free nation. She identifies herself as a Dalit, Buddhist feminist and voices her lived experience as one through literature. While Weave of my life: A Dalit Woman’s Memoir is a direct transcription of her life in the form of an autobiography, MotherWit is an anthology of short stories where she concocts fictitious and real elements together to portray the complexities and hardships of the Dalit community.

MotherWit is an anthology of short stories where Urmila Pawar concocts fictitious and real elements together to portray the complexities and hardships of the Dalit community.

The characters of MotherWit, mostly women, are individuals living in a caste-rigid, patriarchal society. They recognise their plight as someone doubly marginalised owing to their gender and the community to which they belong. Her narrative is hardly ever fraught with angst or is polemical, it is firmly assertive at best and revolutionary within itself. The women in the short stories in MotherWit acquire their agency and autonomy through their own actions. This assumption is simply a part of Pawar’s creative process and in no way is this reductive of women who have it harder and are still not empowered yet.

Also read: Towards A Dalit Feminist Standpoint – The Emancipatory Project For All Womxn

Exploring The Complexities Of Womanhood

Even though the caste identity is operative at several levels, Urmila Pawar doesn’t restrict her narrative of MotherWit to just that. She transgresses to voice her hardships as a woman, an Indian woman, stuck within the webs of patriarchy.

One of the stories in MotherWit, Woman as a Caste (Baichi Jaat), deals with the experience of a woman who refuses to conform to a society that enables men to practise polygamy. The protagonist in the story realises the practice not only puts the wedded wives in a vulnerable position but also pits women against women to secure a higher position, both at a domestic and societal level. By divorcing her husband, she rejects patriarchy and its dictates to reach her emancipation as a woman.

Yet another one of the stories in MotherWit recognises women falling prey to internalised misogyny after having lived all her life in a patriarchal society. In the story, Pain (Shalya), Jyoti resorts to a foul play where she exchanges her baby girl for a baby boy from an unwed mother in the hospital she goes into labour. Despite the heinous act, her maternal instincts don’t leave her and Urmila Pawar keeps her reader sympathetic to the woman.

Caste And Gender Identity

She fondly talks of her mother in Mother (Aaye) in MotherWit, narrates how after the death of her father, she refuses to give up the land and resort to living under her in-law’s authority. It is harshly reflective of the harassment a woman without a man is subjected to in a man’s world. The location of the story at the start of the anthology of MotherWit is telling of how the first feminist experience she was a part of, is through her own mother, so symbolically making the story a parent to her feminist consciousness.

In The Odd One (Vegli) in MotherWit, there’s a strong sense of alienation and detachment central to the protagonist. Nalini feels isolated as a Dalit person in her professional space while feeling neglected as a daughter-in-law among her spiteful in-laws. She has to bear witness to ignorant discussions on the reservation system among her upper-caste colleagues. The climactic scene where she walks away from her husband’s house to move into her new flat is symbolic of how she walks away from everything that oppresses her to claim her own agency and autonomy.

Caste Consciousness And Mental Illness

The caste system deeply embedded in our social fabric runs seamlessly even through the NRIs residing in the West. Circle (Vartool) in MotherWit talks exactly about that. Netra, a young Indian artist, plans to escape from the dowry-mongering, caste-icky marriage culture by relocating to Mauritius. She seeks help from the narrator of the story to find her a good Mauritian match, only for the latter to find that the caste consciousness among the Indians travels a full circle around the world.

In another one of her deeply moving stories in MotherWit, My People (Maajhi Manse) Urmila Pawar talks about mental illness and coparcenary rights. A woman in a rural Indian household is shown to be emotionally and economically exploited that pathologically manifests into a mental illness. The title of the short story in MotherWit is ironically suggestive of a woman’s chronic loneliness in the society where she has been constantly alienated because of her identity as a woman, and later as a madwoman.

Urmila Pawar’s Buddhist Identity As A Reactionary

Freedom (Mukti) in MotherWit records her identity as a Buddhist and her knowledge on the Buddhist literary texts. Her conversion to Buddhism dates back to 1956 in the event of mass conversion of Dalit people into Buddhism by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. The act was a symbolic rejection of the strict Brahmical codes in Hinduism that has systematically oppressed and ostracised Dalits. Urmila Pawar allegorises the story of women spiritual leaders in Buddhism. It is a modern retelling of Kundalkesha, an emancipated woman idealised by the Buddhist religion.

One, as a reader of MotherWit, can read into the narrative and voluntarily draw parallels of Kundalkesha with the docile and submissive women idealised in Hindu religious texts and come to conclusions of their own.

Veena Dao’s translation of MotherWit is lucid and while it is a little difficult to record some dialectical variations in English language, she retains the nativity of the storytelling.

Also read: Revisiting Deccan Development Society: A Tale Of Dalit & Marginalised Women Saving The Environment

Confessional And Personal Narrative

Despite having some fictional elements, Urmila Pawar mostly draws from her personal experiences to create her stories and her characters in MotherWit and other books. MotherWit is a highly personal narrative and as Veena Deo correctly points out: “Women have responsibilities outside domestic sphere; and time and energy are short.”

Veena Deo’s translation of MotherWit is lucid and while it is a little difficult to record some dialectical variations in English language, she retains the nativity of the storytelling. Her introduction to MotherWit responsibly recognises her experience of translating the work despite not having any lived experience as a Dalit woman. So any essence lost in translation of MotherWit is only linguistic and not an appropriated version of Urmila Pawar’s narrative.

About the author(s)

Sonia spends most of her time reading feminist novels, or watching The Office episodes. As much of a cliche as she would have liked it to be, she doesn’t own a black cat.