As much as our country fears conversations around the word and the act of sex, especially outside the institution of marriage and/or for pleasure, the liberal and feminist circles which do widely dicusss sex, sexuality and the common anxieties around them, often tend to overlook one of the most prominent and anxiety-inducing notions—‘unsafe’ sex. In 2013, it was revealed that unsafe sex was the “second riskiest behaviour for boys and the greatest single risk to the health of girls,” in the worldwide risk table.

Although this particular study projected its findings solely on adolescents, unsafe and unprotected sex impacts other age groups too. Institutions of marriage, education and family, entwine with each other whereby factors like child marriage, lack of sex and sexuality education in schools and misogynistic structures engender diverse sexual and sexually violent episodes, especially for women and marginalised groups.

Before we begin to elaborate and complicate the idea of what counts as ‘safe’ or ‘unsafe’, and the varied and multidimensional power relations that work behind the decision-making of having a certain kind of sex, we need to discuss what constitutes ‘sex’.

Sex And Sexual Violence

Contrary to the conventional claims of our society, sex is not merely peno-vaginal penetration. This hetero-patriarchal idea limits the prospects around the varying ways of having sex and expressing sexualities and therefore, in essence, they are anti-queer and anti-trans hypotheses. They reiterate the age-old perception of sex solely encompassing the act of inserting the ‘male genetalia’ or the penis into the ‘female genetalia’ or vagina. Theorists like Simone de Beauvoir, Judith Butler have challenged these biomedical projects of conveniently putting genitalia into neat boxes of ‘femininity/masculinity’, which consequently have socialised people into defining what constitutes ‘deviance’. Predictably, being queer or transgender is conventionally understood as an ‘anomaly’. The colonial sodomy law, for example, which criminalised anal sex, citing that such acts are ‘unnatural’, was legislated as a part of the Section 377 until very recently (September 6, 2018).

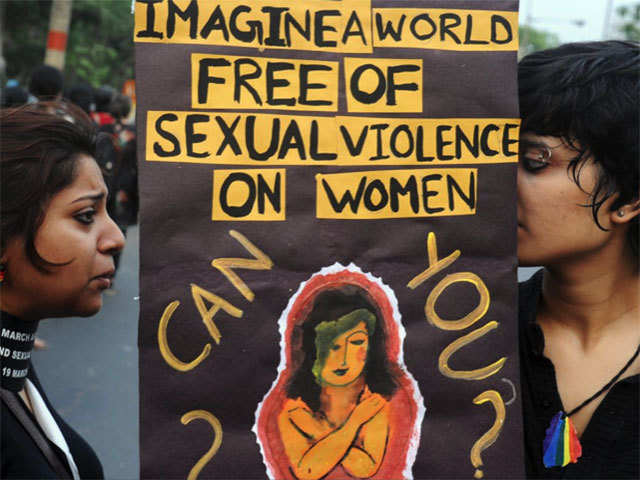

Although historically, sex and sexual violence were both understood through such narrow, patriarchal definitions, feminists and activists have attempted at challenging them. Following the recent public outrage against the rape cases which were amplified by the Indian media,—such as the December 16, 2012 case in New Delhi—these parochial definitions have been somewhat reviewed and revisited. However, despite such outcry, sex and sexual violence in common parlance, is still deemed with its traditional meanings. The denial to acknowledge marital rape and the refusal to institutionsalise a law against the same, is a prime example in India.

It is important to locate the varying experiences around unprotected sex in the purview of sexual violence because often these two categories overlap, giving rise to complex situations where lines of consent are breached coercively through emotional manipulation within a misogynistic social order. For example, stealthing, which is the violent act of removing the condom without the consent of the sexual partner(s) is an oft-heard narrative, especially from women. This increases the risk of STDs and could lead to the possibility of a (often unwanted) pregnancy.

The lack of health resources paired with the shortfalls of awareness programmes around sex, sexuality and the use of contraception—all act as catalysts to the increasing health risks around unsafe sex. It is here, that we need to emphasise the intersectional dimensions of health risks related to unsafe sex. Gender minorities, sex workers and people from other minority groups inevitably find themselves in high risk groups, as other aspects such as livelihood, proper education and resources are denied to them by the unequal power structures in society.

What Is Unsafe Sex?

The inquiry into the notion of ‘unsafe sex’ would necessarily demand a preliminary definition of ‘safe sex’. A 1998 publication defines ‘safe sex’ as,

“Consensual sexual contact with a partner who is not infected with any sexually transmitted pathogens and involving the use of appropriate contraceptives to prevent pregnancy unless the couple is intentionally attempting to have a child.”

Such definitions are exhaustive and often fail to grasp the entire ambit of sexual experiences. As pointed out by other critics, the above definition is not in tandem with sexual encounters where the proper use of contraception (say, a condom) with an infected partner would not necessarily pose a risk of infection.

Common narratives around sex would mostly put ‘unsafe’ and ‘safe’ sex as antithetical to one another, whereby certain sexual acts would unquestionably be boxed into these two categories. Yet, considering how in real life, the boundaries between both are far more intricate and blurred, it is pertinent that we understand that sexual intercourse in itself does not necessarily place someone at risk of contracting an STD/STI, unless the person’s sexual partner(s) themselves are carrying an infection that can be transmitted. Hence, ‘unsafe’ sex is defined by the context in which it has taken place.

Furthermore, socio-cultural contexts also play a very significant role in determining and defining ‘unsafe’ sex. In India, for example, sex outside marriage is often discouraged as it poses the risk of unwanted pregnancies, especially due to the fact that pre-marital sex as an act is highly frowned upon in our country. However, once a person, especially a woman, is already in a marriage, their ‘safety’ no longer continues to become a topic of apprehension.

Here in this context, ‘safety’ almost always signifies the patriarchal honour that is believed to rest within the body of women, reiterating misogynistic concepts of ‘virginity’ and ‘chastity’. I highly doubt whether married women have a say in decision-making when it comes to using contraception during sex with their husbands. Even if it is, the responsibility of using contraception often falls on the shoulders of women—birth control pills being one of the leading ones. What this also reinforces is the idea that contraception post marriage must only be relegated to pregnancy and child-birth related concerns.

So then, can married people not have ‘unsafe’ sex?

What happens if we ideally wanted to avert an unwanted pregnancy and are successful in doing so, but in the process we end up with an STD/STI? Is that ‘unsafe’ sex?

Is there no way to have a strict definition for ‘unsafe’ sex?

Answers to these questions can be many and they will definitely differ from person to person and context to context; however, we still need to identify ways of defining these categories of ‘safe sex’ and ‘unsafe sex’ with respect to its ‘risk factors’. What this means is that, although we cannot have a priori or homogenous idea of what all can constitute as ‘unsafe sex’, we still can delineate factors which result in situations that lead to life-threatening diseases, bodily infections, social stigma and violence. In a world where HIV/AIDS have claimed so many lives—almost 20 million in 20 years—and an estimated 340 million curable sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) causing ill health for many, occur every year—unsafe sex is inadvertently one of the leading top ten risk factors to health worldwide.

Hence, there is a dire need to understand and educate ourselves about what high-risk sexual behaviours are, and what consequences can they produce that might jeopardise not only our lives but also that of the people around us.

Also read: Contraception Beyond Condoms: The Many Kinds Of Birth Control

What Factors Influence Our Decision-Making Around Contraception?

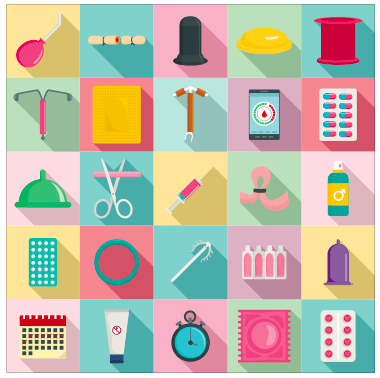

The use of contraception comes with various factors that influence the decision-making process of using them. For example, STD tests before engaging with a new sexual partner(s), or a proper awareness of your partners’ past history of sexual encounters and the knowledge of multiple sexual partners—all of these play pivotal roles while deciding on whether to opt for contraceptives or not.

The scope for unsafe sex, as discussed earlier, extends to STIs and STDs and therefore, the feeling of ‘un-safety’ during sexual intercourse must expand itself to actively include infections as an equally important factor for using contraceptives, as are unwanted pregnancies. While most of us are aware about the popular forms of contraception, such as the condom or the birth control or oral contraceptive pills, barrier methods, the intrauterine device (IUD) or sterilisation, the world of contraception has way more diverse range of options which could be used to prevent sexually transmitted infections or avert present or future pregnancies.

However, contraceptives are still most popularly used with the intention to avoid unwanted pregnancies, which otherwise may lead to unsafe abortions, especially in developing countries. An unwanted pregnancy not only causes mental stress for the pregnant person, but it could also cause mistimed births, maternal and perinatal complications and even violence by their immediate surroundings thereby posing risk to the life of the pregnant person. Given the stigma around abortions, especially for unmarried women, the pregnant person is likely to have an unsafe abortion despite having laws in India that promise to protect them. Hence, contraception, whose motto may be read as ‘prevention is better than cure’, where the ‘cure’ could even be life-threatening, makes them a fundamental part of pregnancy-related concerns.

Although we cannot have a priori or homogenous idea of what all can constitute as ‘unsafe sex’, we still can delineate the ways which result in situations that lead to life-threatening diseases, bodily infections, social stigma and violence. In a world where HIV/AIDS have claimed so many lives—almost 20 million in 20 years—and an estimated 340 million curable sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) which cause ill health for many occur every year—unsafe sex is inadvertently one of the leading top ten risk factors to health worldwide.

Conclusion

While sex and sexual encounters are popularly imagined as matters of private and intimate concern, it is important for us to realise that the degree of ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe-ness’ is highly dependent on the collective or the population of a region or a nation. This becomes more apparent when demographic health surveys conducted by world organisations like WHO reveal that most of the health risks or infections are mapped in developing countries. A study also reveals that most people who are infected with STDs such as HIV, often fail to diagnose themselves and hence, the presence of an infection remains undetected. This, then propounds even more complex challenges to prevent and control the infection within a given population.

The lack of health resources paired with the shortfalls of awareness programmes around sex, sexuality and the use of contraception—all act as catalysts to the increasing health risks around unsafe sex. It is here, that we also need to emphasise the intersectional dimensions of health risks related to unsafe sex. Gender minorities, sex workers and people from other minority groups inevitably find themselves in high risk groups, as other aspects such as livelihood, proper education and resources are denied to them by the unequal power structures in society.

Also read: A Western Feminist History Of Oral Contraception

Hence, the dilemmas around contraception and the project of alleviating health risks, calls for a more holistic understanding of the target population and the societal norms within which we live. The sensitisation process around contraception demands to have more in-depth conversations around the social and cultural factors that govern ideas of ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’. It also insists us to see who is targeted as primary subjects of contraception, who is involved in its economy, how they are advertised and marketed and who has access to these resources.

Unless researchers, policy makers and decision makers delve into these areas, health risks from unsafe sex will continue to thrive and affect the bodies of the marginalised, both in the larger picture at structural levels as well as in intimate partner relationships.

This article is published as a part of the #MyBodyMyMethod awareness campaign on contraception. Feminism in India and Find My Method will be talking about the various forms of contraception, busting contraception myths and taboo and much more throughout the month of September, 2020. Find My Method works to provide accurate contraceptive information for a global audience. You can find localised information that is easy to understand, and is globally representative on Find My Method’s website and forum. You can follow them on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Featured Image Source: Thrillist

About the author(s)

Pragya is a Master's Graduate in Sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She works as the content editor at Feminism In India. She is also a ramen enthusiast, a hummus mother, a postcard hoarder and a wannabe cat lady. She still prefers writing on her notebooks, rather than on her laptop, but her job demands her to do just the opposite. Her favourite season is spring, and her alter ego is that of Mrs. Dalloway who said, "She would buy the flowers herself", in case no man ever buys her any!