Caste is conveniently swept under the carpet in spaces that have been monopolised by dominant caste groups. There is little to no discourse surrounding the evils of caste in these spaces and caste-based discrimination is regarded as a non-issue. Simply put, caste tends to escape the savarna imagination, although discriminatory structures of caste are meticulously upheld by the Savarnas. In India, caste is all-pervasive and has shaped lives and livelihoods from time immemorial, whether dominant caste folks choose to acknowledge it or not. It is exceedingly common to hear casteist notions being perpetuated in one’s everyday interactions. This list seeks to highlight a few redundant casteist myths that we need to put to rest, once and for all.

- Caste is a thing of the past.

This is among the most common myths that one is bound to hear at some point in their lives. This argument stems from the fallacious notion that caste has been done away with in post-independent India owing to certain constitutional safeguards.

The fact is that, caste is an institutionalised structure of discrimination. It is greatly entrenched in the social fabric of not just India but even other South Asian countries. It determines the level of access of opportunities to employment, education and ownership of resources of communities. Caste shapes the most important aspect of our lives — where we live, how our relationships play out and how much social mobility we get to have.

Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi communities have borne the brunt of casteist violence in the Indian establishment and still continue to do, as I write this. Members of these communities are rampantly harassed and lynched due to their identities. These cases are barely ever highlighted by the Brahminical forces that occupy media spaces. Caste-based discrimination also takes less aggressive forms, ranging from prejudiced treatment of Dalit-Bahujans in academic spaces to the condescension expressed towards domestic workers. Thus, given the overarching character of caste in the Indian setting, it cannot be invisibilised by dominant caste folks. Caste thrives even today.

Simply put, caste tends to escape the savarna imagination, although discriminatory structures of caste are meticulously upheld by the Savarnas. In India, caste is all-pervasive and has shaped lives and livelihoods from time immemorial, whether dominant caste folks choose to acknowledge it or not. It is exceedingly common to hear casteist notions being perpetuated in one’s everyday interactions.

- Caste only exists in villages.

Dominant caste folks throw around this argument and then proceed to flaunt their markers of caste — sacred threads and marks worn on foreheads — in the same breath. This argument emerges from the misinformed belief that caste-based discrimination only manifests itself in the form of gruesome physical violence. However, caste is as much an urban phenomenon as it is a rural phenomenon.

“In the popular imagination, caste is the key marker of identity only in villages. In contrast, cities are often seen as sites of emancipation, where even the lowest in the caste ladder has better access to public goods, and greater opportunities in life. Much of this is based on anecdotal evidence, and has rarely been backed by empirical research.”, writes Pranav Sidhwani.

Residential segregation on the basis of caste is a prominent feature of urban India. In India’s biggest cities, Dalit communities live in clusters. Their neighbourhoods lack basic amenities such as piped water and toilets. Furthermore, caste-based occupational structures also actively function in cities, wherein Dalit individuals are relegated to ‘menial’ jobs in the informal sector. This sort of segregation has its roots in the practice of untouchability.

Also read: COVID-19: How Casteist Is This Pandemic?

Caste also operates in more covert ways in cities. A distinct feature of several Indian languages is that they are spoken differently by different communities due to social stratification. This compounds to the othering of oppressed caste groups. Caste-based endogamy is also a key instance of how casteism manifests itself in cities.

This video by @sumeetsamos on Instagram succinctly busts this myth.

- Reservation should be granted on the basis of economic status.

Dominant caste folks whine about reservation — in the spheres of employment, education and political representation — all the time. They even tend to go to the lengths of saying that reservation policies devalue ‘merit’ and that they promote reverse casteism. These are dangerous misconceptions.

It is important to understand that reservation policies are a means to provide reparations to marginalised communities that have been systematically denied access to opportunities for millennia. They are not a poverty eradication scheme. Merit in our country is a myth. This is owing to the fact that how ‘meritorious’ an individual is, largely depends on their caste location which further determines their level of access to resources and opportunities.

‘The privilege of being from the “general” category allows its beneficiaries to encash its traditional caste capital and convert it into modern professional identities of choice, while pretending that caste does not influence their lives. However, those from lower castes rendered immobile across socio-economic structures, are forced to intensify their caste identities.’, states an EPW article.

The following comic strip on Instagram adequately explains why reservations are necessary—

- Caste assertion by Dalit-Bahujans is a dangerous form of identity politics.

Identity politics refers to the tendency for people of a particular religion, race, social background, etc., to form exclusive political alliances, moving away from traditional broad-based party politics. This term is often used derogatorily, especially in the caste context, as it presents a threat to Brahminical hegemony. It is perceived as something that is dangerous and divisive. However, when Dalit-Bahujan communities assert their identities, it shakes the Brahminical order.

Dalit-Bahujan political assertions have been disregarded ever since the founding of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) by Kanshi Ram. Accusations of “identity politics” are mindlessly hurled in debates surrounding caste-based reservations.

As Asghar Ali Engineer wrote, ‘The issue is never simply the assertion of a caste, religious or regional identity by itself, but how identity functions as “an instrument” to access material gains in a power set-up.’ In a society that is extensively polarised by caste, caste-based mobilisations allow marginalised sections that have been betrayed by the system to demand what is rightfully theirs. Such mobilisations offer community support to deprived groups and can prove to be emancipatory. They are also integral to the functioning of a democracy.

In a society that is extensively polarised by caste, caste-based mobilisations allow marginalised sections that have been betrayed by the system to demand what is rightfully theirs. Such mobilisations offer community support to deprived groups and can prove to be emancipatory. They are also integral to the functioning of a democracy.

- Everyday language is free of casteist slurs.

Nothing can be further from the truth than this argument (barring more absurd casteist notions, maybe) Indian languages are riddled with casteist slurs. Their users are either oblivious to the dehumanising connotations of these slurs or are desensitised to them. Our language reflects and perpetuates casteism, and slurs are a powerful tool in the hands of the oppressor class to help retain the status quo.

Certain casteist slurs that are casually peppered in everyday interactions in Hindi include — Bhangi, Chamar, Junglee, Dhobi, Kameeni, Mahar, et cetera. These words represent the names of certain ‘lower’ caste communities that inhabit various parts of India. To use them to describe an ‘uncivilised’ or a ‘misbehaved’ person is very problematic. Some of these casteist slurs have even been outlawed by the Supreme Court, but this barely has an effect on our ground realities.

In 2018, Time Magazine featured the Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein with a caption that read, “Producer. Predator. Pariah.” Pariah is, in fact, a casteist slur which derives from the name of the Paraiyar community of Tamil Nadu. Time Magazine later received backlash for the implicit casteism reflected in its caption.

The far-reaching consequences of the usage of these terms often tend to evade the upper-caste sentimentality. However, it is pertinent for those with privilege to reflect on their speech and eliminate casteist slurs from their vocabulary.

Also read: Honour Killing: India’s Own Pandemic Of Casteist Patriarchy

Conclusion

These myths barely scratch the surface of the deep-rooted casteism in Indian society. Therefore, it is important to listen to and read the works of anti-caste activists. Caste must be included in mainstream discourses, for it will not go away if we do not talk about it.

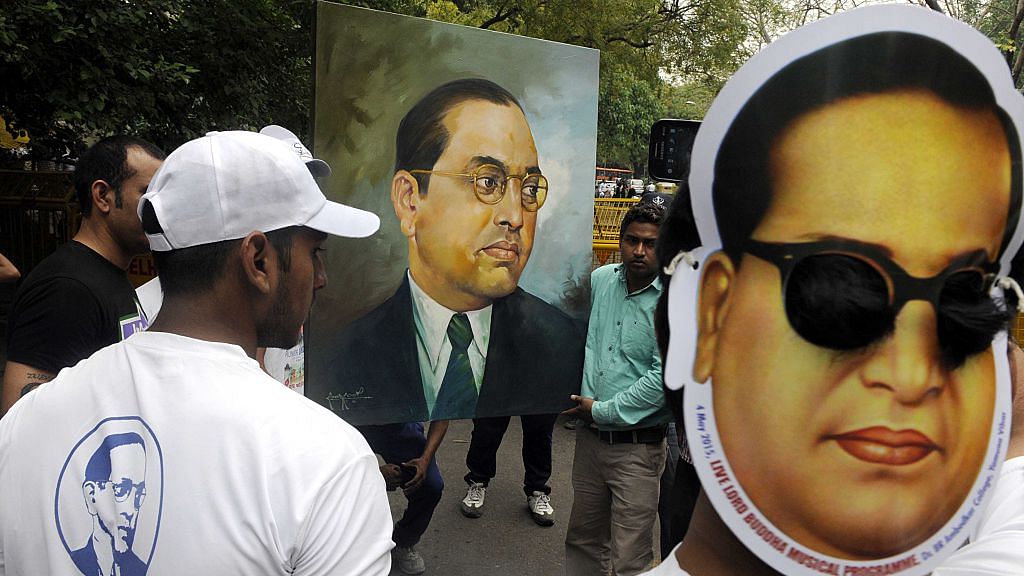

Featured Image Source: National Herald

About the author(s)

Kavin is an economics major. She can usually be found seeking contentment from her bookshelf and the occasional biriyani. Among other things, she has a soft spot for Chennai and misses the city whenever she's elsewhere.

Humari galti hai hum brahmin parivar me paida hue

I think this article is one sided. You could have neutral assessment. You want to show pain of only one side.