India’s handloom sector has been in a state of crisis for many years but in the past few months, the industry has been facing an unprecedented sea of economic and social challenges. The global economic slowdown that countries are currently reeling under has severely impacted the livelihood of millions of artisans across India. Globally, the retail industry is experiencing a sharp decline in business as consumers are either refusing to spend or are unable to spend. This change in consumer behaviour in the wake of the COVID 19 pandemic is partially a result of rising unemployment and steps taken by employers to cut down on wages.

Several retail companies are actively considering either liquifying their businesses or declaring bankruptcy. The financial state in which retail businesses globally find themselves in today has direct consequences for Indian artisans who supply them their products. An alarming number of artisans and weavers are reporting that they are unable to sustain themselves and their production process due to lack of income.

According to some commentators, the present situation has egregiously worsened with the government’s decision to abolish both the All India Handlooms Board (AIHB) and All India Handicraft Board. The AIHB was established to facilitate the Central Government in formulating policies and schemes that would promote the development of the handloom sector. It was also supposed to aid the government in creating new employment opportunities within the sector and devise welfare schemes for artisans.

The financial state in which retail businesses globally find themselves in today has direct consequences for Indian artisans who supply them their products. An alarming number of artisans and weavers are reporting that they are unable to sustain themselves and their production process due to lack of income. According to some commentators, the present situation has egregiously worsened with the government’s decision to abolish both the All India Handlooms Board (AIHB) and All India Handicraft Board.

The Board earlier comprised of several key stakeholders including weavers and artisans, who considered the platform a forum where workers could raise their problems. On July 27th, however, the Indian government abolished the Board in order to promote what government officials call “a leaner government”. This decision has been widely criticised for not including artisans in the decision-making process and for destroying the last platform where handloom sector workers could assert their rights and seek accountability.

According to government sources, the decision was taken to help achieve “minimum government and maximum governance.” The move was criticised by individuals like Laila Taybji, founder of Dastakar, for dismantling the last forum where workers could raise their concerns. Others embraced the decision by observing that the AIHB was a toothless tiger that achieved little on the ground in terms of ensuring workers’ welfare.

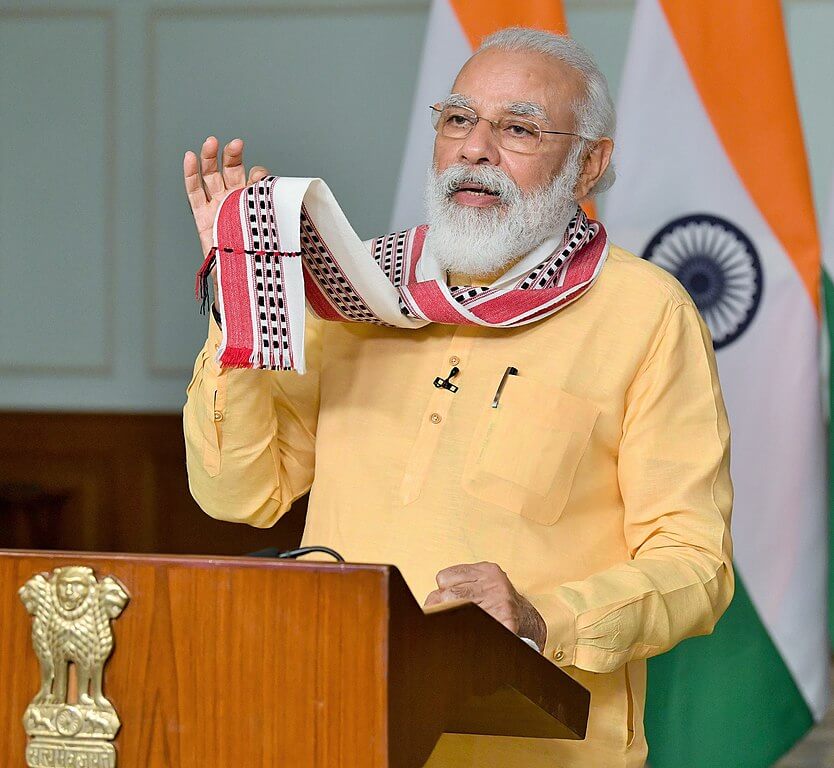

Interestingly, the move to abolish AIHB was taken days after the Prime Minister’s Independence day speech in which he encouraged citizens to become “vocal for local” by buying products made in India. This, according to the Prime Minister, would help India become “atmanirbhar” or self-reliant. In order to adequately anticipate the possible consequence of such a drastic step on poor handloom workers, we must look briefly at the existing economic conditions in which handloom workers currently find themselves in.

The Ongoing Crisis

Before AIHB was abolished, demonetisation devastated the sector, rendering much of the existing cash in the hands of workers useless. Lack of cash meant workers could not buy raw materials which slowed down the production process, eventually forcing owners to shut down their mills. A few months later, as the industry was on the verge of a gradual recovery, the government introduced the Goods and Services Tax (GST). As per law, GST is applicable in case of all enterprises that have an annual turnover of Rs 20,00,000 lakh. According to a report published by Newslaundry, wholesalers, in order to reduce their expenditure, have started deducting 5% of mandatory GST payment from workers’ wages. To make matters worse, taxes on brocade, silk and dye have further increased the production cost.

The pan India lockdown, which was announced in the month of March, further exacerbated the woes of handloom workers. Millions of craftspeople in India are sitting on stocks of clothing that they cannot sell. Some of these workers anticipate that even with the best of their efforts, it would take two years for this stock to be sold. Despite the government’s emphasis on encouraging local handloom production, the budget allocation for the year 2020 stipulated a mere Rs 485 crore the entire sector.

Activist Laila Tyabji, in an interview with Leaders for Social Change, observed that the paradox plaguing the Indian Textile sector is how despite the sector’s huge contribution to the country’s GDP, government investment in the field has progressively declined since the first five-year plan. The textile sector also remains the second-largest source of employment for Indians after agriculture. According to official records, 4.3 million people are part of the handloom sector. This too is a conservative estimate as most government documents only record handloom owners in their list of workers, overlooking several children and women who support them with allied services. Several women who perform the actual act of weaving also are often left out of this list as they do not own handlooms.

The pan India lockdown, which was announced in the month of March, further exacerbated the woes of handloom workers. Millions of craftspeople in India are sitting on stocks of clothing that they cannot sell. Some of these workers anticipate that even with the best of their efforts, it would take two years for this stock to be sold. Despite the government’s emphasis on encouraging local handloom production, the budget allocation for the year 2020 stipulated a mere Rs 485 crore the entire sector.

Women Handloom Workers

The handloom industry has historically been a household-based enterprise which has persistently faced the threat of unfair competition from modern industries. This long-standing challenge has exerted considerable stress on the handloom sector for decades. Having said that, women within the sector have been severely impacted by the handloom sector’s gradual ruination. According to the Third Handloom Census (2009-10), out of the total number of workers within the sector, 57.6% workers are women. In the North East of India women comprise 99% of all handloom workers in the region. Even after women’s immense contribution to the field, their work and participation continue to not be adequately acknowledged.

For a long time, it was assumed that women only engage in allied activities surrounding the main weaving process. This argument was used to justify women’s exclusion from the list of workers in the census. Policy expert Narsimha Reddy argues that women perform close to 25 pre-weaving activities before the weaving process can start. By not recognising women as formal workers, the government deprives them of competitive remuneration for their work and access to employment-related social security benefits. However, over the years, many men have left the industry due to lack of income which has allowed women to take over the production process as primary weavers. Several cooperative societies have since then helped women generate regular income and facilitated the process of skill development.

Also read: How Difficult Is Menstrual Hygiene Management For Women Workers In Indian…

But the supply chain commandeering the production process leads to a situation wherein even if the consumer is paying adequate money for the products, very little money percolates down to women workers. Reddy further points out that a woman spinner earns Rs 10 per boggle which means if she spins 5 boggles a day, she earns Rs 50 in wage, which is much less than the minimum wage. As a result, many families have started to move away from cotton weaving and have started producing silk cloth. But over the years silk, too, has lost its capacity to generate income as fake textile has started to flood the market. The government till-date has been ineffective in regulating the market suchin a way that prices of textile products remain competitive and ensure dignity for Indian textile workers.

It is women working in the handloom sector who have managed to keep families afloat in times of economic crisis through performing multiple odd jobs. But often such inferences are falsely attributed to women’s inherent entrepreneurial nature rather than opening a dialogue about women’s status in society. Women in India, who function within the patriarchal institutions of marriage and family, are unable to escape performing unpaid labor within the family and poorly paid labor outside.

Having said that, studies conducted in the field of women’s work indicate that the ability to earn a regular wage enhances women’s social status, including that within the family. Some studies also argue that working women are less likely to tolerate domestic abuse and violence. Through such data one can easily estimate the importance of work in women’s lives. Therefore, it is a matter of grave concern what would be the result of the ongoing crisis on women workers within the handloom sector.

It is women working in the handloom sector who have managed to keep families afloat in times of economic crisis through performing multiple odd jobs. But often such inferences are falsely attributed to women’s inherent entrepreneurial nature rather than opening a dialogue about women’s status in society. Women in India, who function within the patriarchal institutions of marriage and family, are unable to escape performing unpaid labor within the family and poorly paid labor outside.

We are living in an age where fast fashion brands are able to sell T-shirts worth $5. The price tag, however, masks the many social and environmental costs of production that goes into bringing that T-shirt from the factory to the consumer. Since clothes produced in the traditional handloom sector are labour intensive, they are unable to sell their products at the same competitive prices as multinational companies. Such unfair trade practices are wreaking havoc on the handloom sector, wherein sustainable practices are used to generate cloth.

The Possible Impact of the Abolition of AIHB

The decision to abolish AIHB will result in the systematic dismantling of the only bridge between handloom workers and the government. From the data available, one can say with some certainty that the government was adequately spending / investing / etc neither on AIHB nor on the handloom sector, at large. It is therefore concerning why a seventy-five-year-old Board was hastily abolished in the absence of any new reforms or welfare schemes for handloom workers.

Also read: The Impact Of Covid-19 On Assam’s Women Weavers

There are some commentators who argue that the board was closed down as a cost-cutting measure while others are of the opinion that it is a strategy to give private players a greater role in the handloom sector. Whatever may have been the case, it is clear that Indian textile workers have lost the last platform of asserting their rights as informal sector workers and the symbolic presence of a democratic institution built to aid workers’ welfare. More specifically a decision of this magnitude will impact women weavers more dramatically than their male counterparts.

About the author(s)

Pritha has recently finished her Master's in Women's Studies from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Academically, she is keenly interested in issues of reproductive justice, crip theory, and contemporary feminist activism. In her free time, she loves to paint with watercolours and watch art tutorials.