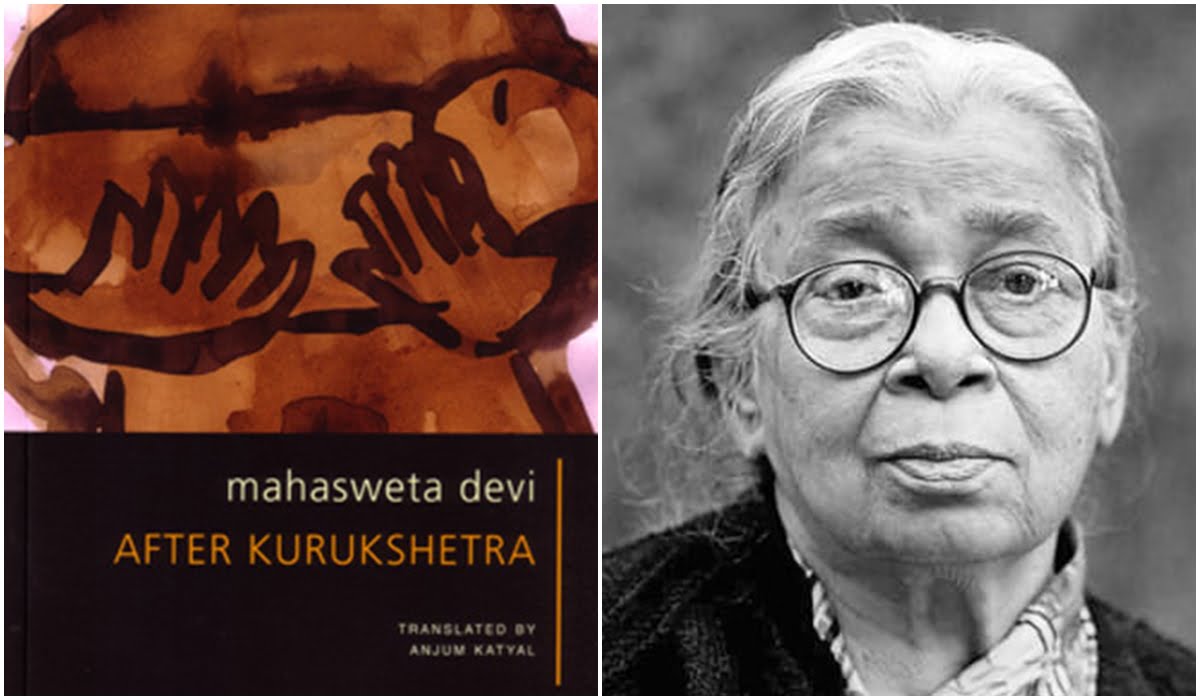

Mahasweta Devi (1926-2016) was one of India’s finest writers who wrote and spoke vociferously for the rights of women, tribal and adivasi people. Her books and short stories were primarily written in Bangla and then translated in several other languages including Hindi and English. This is a review of her book After Kurukshetra consisting of three short stories, published in 2005 and translated from Bengali by Anjum Katyal.

The first story in After Kurukshetra begins right after the ‘great, holy’ war at Kurukshetra has ended. But instead of giving us an account of the heroes of the war, Devi takes us on a journey exploring the lives of those that the war neglected and demolished. While Vyasa’s Mahabharata might be of an intimidating length, Devi’s After Kurukshetra starts and finishes within 53 pages. Yet, Devi successfully manages to produce a clear, loud critique of Mahabharata. She writes, “…This, a holy war?! A righteous war?! Just call it a war of greed!”

Also read: No Country For Women: Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi In A Hindutva Regime

While Vyasa’s Mahabharata might be of an intimidating length, Devi’s After Kurukshetra starts and finishes within 53 pages. Yet, Mahasweta Devi successfully manages to produce a clear, loud critique of Mahabharata. She writes, “…This, a holy war?! A righteous war?! Just call it a war of greed!”

The Five Women (Panchkanya)

Devi’s first story in After Kurukshetra revolves around five widowed women. These women belong to the janavritta (common folk) and their husbands have died fighting at Kurukshetra. Devi captures the death and destruction of this ‘holy war’ in a devastating manner when she writes, “The earth of Kurukshetra was scorched rock hard by the funeral fires.” After Kurukshetra tells the story of the five women who came to watch the war hoping for their husbands’ safe return cannot go back to their village because they cannot cross the land of Kurukshetra where so many funeral pyres have been lit that the ground itself is like “waves of angry heat”.

Godhumi, Gomati, Yamuna, Vitasta and Vipasha – the five women – are convinced to become companions of a pregnant Uttara, whose husband Abhimanyu also died in the battle. Through Devi’s narrative in After Kurukshetra we know that the meaning of widowhood is different for the five women companions and Uttara who belongs to the rajavritta (royal household). While Uttara finds herself in the middle of customary restrictions, the five women sing their sorrow, laugh and chat with each other and also inform Uttara that custom asks them to return to their village and get re-married. At this Uttara, a young woman, wonders of her own days of childish naivete and if those will ever return to her.

At one level in After Kurukshetra, Devi focuses on displaying the apparent freedom of the janavritta. While the rajavritta women are entangled in the image they need to produce and re-produce of ‘ideal widows’, the janavritta women enjoy more mobility and agency. When Uttara asks the women to stay with her longer they refuse. “These are chambers of silence,” they tell her. Everything happens outside of the women’s chambers here.

At the same time, Devi comments on how war makes victims of women in a patriarchal society in After Kurukshetra. The five women lament the loss of their husbands as the loss of workers, as the loss of the farmers of their lands. For though they seemingly experience more mobility, the janavritta women also experience economic exploitation and dependence, which is a contrast that Devi attempts to show in After Kurukshetra. With their husbands gone the only thing that will bring them back economic security will be another man, another marriage.

Kunti And The Nishadin (Kunti o Nishadi)

The second story of After Kurukshetra is about Kunti. After the war, Kunti pledges to spend the rest of her life with Dhritarashtra and Gandhari in the forest. Kunti spends her time taking care of the old couple and wondering about her own mistakes leading upto the war. She finds herself often sitting in the forest and apologising for the things that she kept hidden and her selfish demand from Karna. She often sees a Nishadin (woman belonging to the Nishad tribe who spend time hunting and foraging in the forest and are deemed ‘uncivilised’) listening to her as she apologises aloud. Kunti dismisses the Nishadin’s presence for she knows the Nishadin can’t understand her language.

But one day when Kunti is done with all her apologies, the Nishadin speaks to her and asks – When will Kunti confess her greatest sin? She reminds Kunti of the family of six she sacrificed to save herself and her sons in the house of lac that she burnt. She took in a family of a travelling Nishadin and her five sons, served them wine so they’d sleep in the house and then fled and burnt the house. Their bodies were found charred and it was believed that the Pandavas and Kunti were dead. The Nishadin confronts Kunti and asks her – How many times have you invited a Nishadin to a feast? And how many times did you serve them wine? Just that one time?

This in After Kurukshetra is a story of retribution and revenge originating from a selfish act of injustice. For Kunti, the bodies of the Nishadins were so killable that they did not even find mention in her guilt. For the Nishadin, however, this was another act in the systemic marginalisation of her people by the rajavritta who in their own game of brother vs brother, put thousands of lives up as collateral damage. After Kurukshetra manages to bring this out strikingly well in the conversation between Kunti and the Nishadin.

Devi’s sharp words on caste and class divisions stand true even today. It’s as if she is saying war is for the privileged and by the privileged.

Souvali

Devi seems to have focused more on stories from the Mahabharata that can be found in between the lines in After Kurukshetra. She hardly speaks of the Kauravas or Pandavas or any of the heroes of the war. When she does speak of them, there is a palpable resentment. Souvali is one such story. Souvali was a vaishya (courtesan) who bore a son by Dhritarashtra. The son was named Yuyutsu. After Dhritarashtra dies, Yuyutsu – his only offspring alive – is called upon to perform the last rites. After the last rites, he returns to Souvali’s hut. The mother and son discuss their grief at being discriminated against and being excluded by the Kauravas. Dhritarashtra refused to bestow any kindness on Yuyutsu but took him away from his mother for combat training.

After Kurukshetra show how their separations caused them pain and grief and Souvali spent her life waiting for her son’s return. They speak about Dhritarashtra being insufferable and Gandhari always ill-treating Souvali. Souvali refuses to observe the last rites for Dhritarashtra as per custom. She says, “I’ll let my own Dharma tell me what’s right.” But as her son Yuyutsu praises the Pandavas for their kindness, After Kurukshetra shows Souvali wondering when will he realise that even they will not accept him as their own?

Also read: Mahasweta Devi: An Eminent Personality In Bengali Literature | #IndianWomenInHistory

After Kurukshetra delivers us into the nooks and crannies of Mahabharata. To be able to wonder what happened to the Nishadin and her sons who died just so the Pandavas could save themselves, to be able to ask who were they is an act of defiance by Devi.

After Kurukshetra delivers us into the nooks and crannies of Mahabharata. To be able to wonder what happened to the Nishadin and her sons who died just so the Pandavas could save themselves, to be able to ask who were they is an act of defiance by Devi. Her characters, however, are far from being victims. They steer the narrative in After Kurukshetra. If there are any victims for Devi, they are the rajavritta. Victims of their own greed, power and arrogance. The reasons, as Devi says, for their own downfall.

About the author(s)

Isheeta is a features writer, a student of History and a prospective student of Gender Studies. She enjoys reading historical fiction, philosophy, gender theory and sipping coffee in quiet corners.