Earlier this year, shocking reports out of Madhya Pradesh highlighted the history of forced sterilisation in India. The state government withdrew a circular that had been circulated to officials, directing them to identify staff members in the Health Mission who had failed to get any man sterilised in the previous fiscal year, that ends on March 31st. They were also ordered to persuade more men to get sterilised or would lose their salary and could be forced into retirement.

MP’s Health Minister Tulsi Silawat told the Press Trust of India (PTI) that the order was nullified as its language “wasn’t proper.” People were quick to jump onto the case, stating that such events harked back to the sterilisation drive that took place during the Emergency in the ’70s with Sanjay Gandhi at the helm.

The Sterilisation Emergency

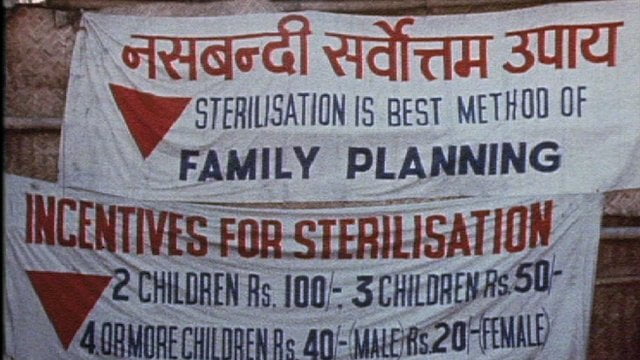

India was the first nation to adopt family planning as official policy—it did so all the way back in 1952. Yet, the funds made available until the mid-1960s weren’t sufficient enough to bring about effective action. Most Indian women in 1965-66 accepted IUDs. After the news about the adverse responses to IUDs spread, its acceptance fell. In 1971, the first vasectomy camp was tried out in Kerala which was a massive success. This spurred the government to carry out similar camps at a larger scale. The vasectomy camp drive was conducted through a mobile-service approach, and incentives were given to those who got sterilised.

The drive to sterilise then gained momentum. The World Bank, the Swedish International Development Authority, The Ford Foundation, and the UN Population Fund had funds available for population control as per The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies and Programs, and India then took on the case of family planning and population control more strictly. The number of male sterilisations increased—in 1970-71, there were 1.3 million, and in 1970-71 the numbers reached 3.1 million. However, in the following year, they fell to 900,000 because of reports of medical problems, due to which the government retreated for a while.

Then, fearing political unrest due to economic and social stagnation, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi launched the Emergency, where all civil liberties were curbed. Her 20-Point Programme on developing the country didn’t mention family planning, yet Sanjay Gandhi’s own Four-Point Programme had this as the one and only priority, and through only one method—sterilisation.

The incentivisation for these sterilisations reached new heights—middlemen like police officials, district authorities, and tax officials along with the doctors themselves feared losing their jobs or facing salary cuts if the target number of people weren’t sterilised.

The incentivisation for these sterilisations reached new heights—middlemen like police officials, district authorities, and tax officials along with the doctors themselves feared losing their jobs or facing salary cuts if the target number of people weren’t sterilised. The family planning programme gained momentum in 1976-77. The number of sterilisations shot up to 81 lakh in just one year. In this year, there was also the decline in IUD cases, along with a drop in using conventional contraceptives (condoms)—from 83.5 percent the previous year to 74.9 percent. This shows how the forced sterilisation programme took over the entire family planning programme, thereby essentially failing as an all-rounded approach during the Emergency.

Women And The Marginalised As Targets

Eventually, the onus of sterilisation on men was reduced and women were more often forced into it—the idea that men’s fertility would be affected and reduced (which still exists), led to women being the ideal candidates for this drive. It may have also been because women were less likely to protest. These coercive sterilisations embodied gendered violence because they occurred even though vasectomies were much easier and safer than tubectomies. However, women saw lesser compensation for the sterilisation themselves, sometimes not receiving any at all. Up to two thousand people died in this drive officially.

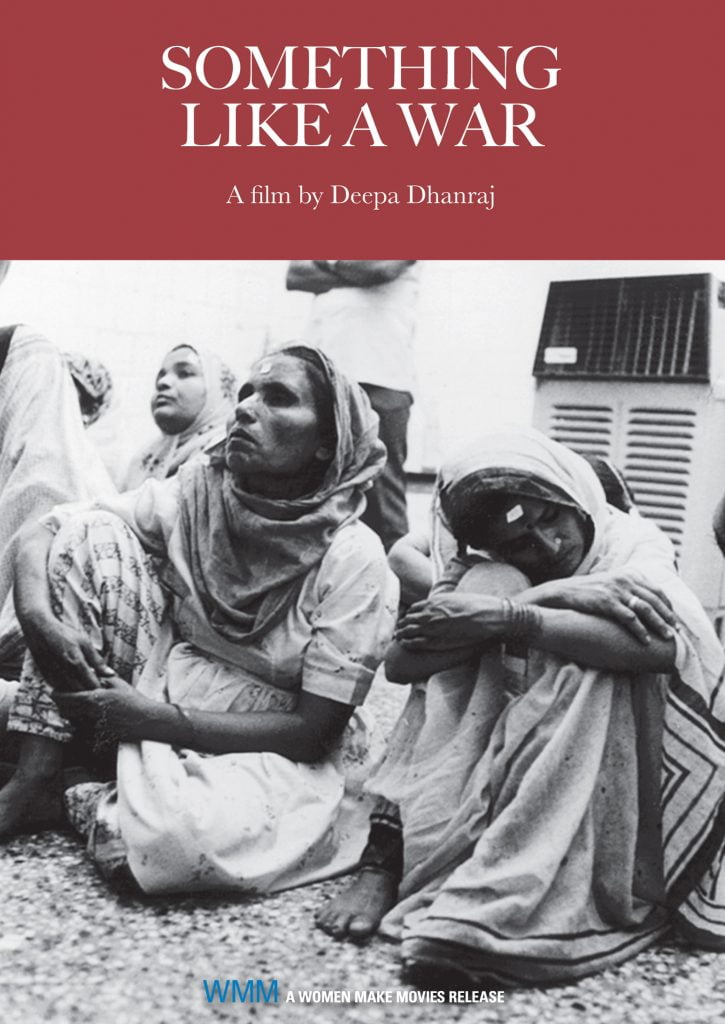

Deepa Dhanraj, a renowned filmmaker, highlights the plight of women who underwent this process in her documentary, while also including the larger social commentary around the sterilisation drive, in Something Like a War.

In an interview with The Conversation, she says,

“With Something Like a War, we wanted to stop the government of India’s coercive targeting of poor women to achieve state sterilisation targets. But we also wanted to address the structural consensual belief that the poor were responsible for their poverty because of excessive bleeding. So in the film we also talked about why poor women made the reproductive choices that they did – they were not foolish, but various social factors influenced their decisions. So we not only had to address the state agenda but also this political consensus that made it acceptable to have a eugenics notion about the poor.”

Cases that were the most “successful” were in Haryana, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh, which highlights both the influence of the Center in New Delhi over the programme and the higher targeting of those who were rural and migrant workers. The targeting of the poor and underprivileged, like the Muslims, Adivasis, and Dalits, showed the inherent bias in this structure, stating higher populations to be the cause of their poverty; also implying that they were more likely to have more children than others would.

Policies that were discriminatory to those with more children were enacted. The Population Research Institute highlights these examples—people with more than three children in Rajasthan were banned from holding any government job unless they had been sterilised. In Bihar, food under public rations was denied to families with more than two children.

This scheme of family planning, which initially was about raising awareness about contraception, providing access to the same, and educating people on the benefits of having fewer children, which was started off as a vasectomy drive, was now focused on getting as many people, men and women, sterilised.

The violence of population control has always been intense in India. The underprivileged and helpless are taken for granted, with the narrative of the poor being poor because of having too many children to feed, while the rich could afford to save themselves from forced sterilisations.

Also read: Women With Disabilities And Forced Sterilization In India

The Present Situation

The violence of population control has always been intense in India. The underprivileged and helpless are taken for granted, with the narrative of the poor being poor because of having too many children to feed, while the rich could afford to save themselves from forced sterilisations. India is projected to overtake China as the world’s most populous country by roughly 2027 according to a United Nations report released last month.

The Indian government is said to have dropped the target and incentive system after the 1994 Cairo Conference on population. Yet as per a research paper published through Birkbeck, it has simply been replaced with ‘Expected Levels of Achievement’ at the state level. The Indian government’s Programme Implementation Plan (PIP) of 2014-2015 shows 1,50,000 tubectomies and 8,000 vasectomies ‘level’ for Chhattisgarh and an increase in this number in the following years.

India has carried out up to 4 million sterilisations during 2013-2014, and less than 1,00,000 of these surgeries have been done on men. Between 2009 and 2012 up to 700 deaths were reported due to botched surgeries. Although technology has improved, and safety measures have been updated for conducting safe sterilisations, the haste to meet the mandated quotas remains.

A 2014 case in Chhattisgarh highlighted the still-dire conditions of sterilisation clinics. Eleven women died after undergoing tubectomies at a government-run health camp. Correspondents state that 83 women were operated on by a doctor and his assistant in just under six hours and that they were all from poor families. Compensation worth $20 was provided to the women. The survivors then received treatment from three different hospitals.

It still stands that men aren’t as involved as they should be in the family planning programmes. The male to female ratio for sterilisation in 2016-17 stood at 1:52 as per data with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. In an interview with LiveMint, Poonam Muttreja, Executive Director of Population Foundation of India, stated that,

“As per National Family Health Survey 4, three in eight men believe that contraception is women’s business and that men should not have to worry about it. The emphasis has been largely on methods for women historically, and there has been little effort to involve men. The low levels of men’s involvement are reflected, to an extent, in the very low use of male contraceptives.”

Also read: How Did COVID-19 Impact Reproductive Health Services In India?

It is more pertinent than ever to change the narrative around family planning as a whole, along with the stereotypes that turn into defining narratives. The poor aren’t poor due to having too many children, it’s due to the lack of a basic income, dependence on agriculture when agriculture fails due to a failing climate, and the lack of a failsafe mechanism when this happens. There also needs to be more of an effort made to get men into these programs as well, be it as the patient or as the educator.

Featured Image Source: Pinterest

About the author(s)

Zoon (she/they) enjoys writing about all things under the sun, but right now sticks to feminism, Islam, and food. She is also fond of the outdoors, art, and reading up on folk cultures.