Much has been said about Zomato’s new policy allowing people who menstruate to take one day off per menstruation cycle. With many weighing in on the implications of ‘period leaves,’ it’s important to remember that the debate takes place in the context of a ‘workplace.’ And obviously, there are two preconditions for the discourse on period leaves—a workplace and pay. But, women (who are a subset of all persons who menstruate) are overwhelmingly represented in the informal sector where they are guaranteed neither good working conditions or fair pay; how do we make room for all persons who menstruate to bleed without precarity?

This article attempts to tackle these questions with a focus on domestic workers. According to conservative unofficial estimates, there are 20-50 million domestic workers in India, of which 75% are women and young girls. Although there is dearth of data on transgender workers, it’s no secret that lower-caste, Adivasi people form the majority of domestic labour in India. If the conversation on menstruation leave exists in the workplace, what do we do if there are no social, political or economic incentives to ensure equity in the workplace? How do we even expand workplace equity to spaces that amplify inequities on a daily basis?

With many weighing in on the implications of ‘period leaves,’ it’s important to remember that the debate takes place in the context of a ‘workplace.’ And obviously, there are two preconditions for the discourse on period leaves—a workplace and pay. But, women (who are a subset of all persons who menstruate) are overwhelmingly represented in the informal sector where they are guaranteed neither good working conditions or fair pay; how do we make room for all persons who menstruate to bleed without precarity?

Working In The Domestic

The domestic ‘workplace’ is a unique space. For paid domestic workers (most women also perform domestic work without remuneration or recognition of labour), the workplace is located in an employer’s private household. In addition, domestic work is often part-time (sometimes live-in) and is organized by class, caste, gender, race, immigration status and ability.

Moreover, capitalist-patriarchal systems that define what qualifies as ‘productive work‘ render domestic work as no work, resulting in no remuneration for domestic work in one’s own household and little remuneration for those employed part-time. Globally, paid domestic labour has been performed by marginalised people—racialised and immigrant women, lower class and caste women. Ideas of paid domestic work as ‘dirty,’ ‘unskilled’ layer the precarity in which many domestic workers operate within. Arguably, working without breaks dovetails into these notions that invisiblise domestic labour.

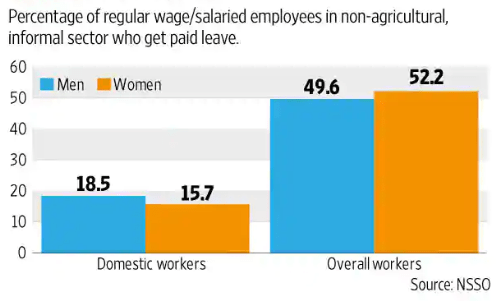

Chart source: Livemint

In India, domestic workers follow a protocol justified by caste, in the upper-class employer’s home—removing footwear, using separate utensils, cleaning but not using bathrooms, and many times allowing policing via verification and time-entries at residential society gates. Conclusively, the workplace is a site of discrimination and violence (sexual or otherwise). Further, this discrimination maintains the existence of domestic labour in the status quo, and hence there are little to no incentives to change outside ensuring better conditions for workers.

No Blood In The Kitchen

For domestic workers, the workplace is hence, a daily experience of discrimination. Worse, it is increasingly hostile when they menstruate. Stigmas not limited to bodies, caste and gender simultaneously force them out of the workspace (without pay) and compel them to continue working (without the option of leave). Most importantly, the absence of incentives for accommodation premise both these pressures.

For instance, there is little to no access to bathrooms to change pads in an employer’s home, unless you are a live-in domestic worker in which case they might have a separate bathroom. Public bathrooms for women are in near unusable conditions. Employers cite veiled (and explicit) casteist reasons for denying toilet access to domestic workers. Reasonably, toilet inequity discourages women to show up to work on their periods.

That menstruation signals “impurity” and renders those menstruating as “untouchable” restricts access to the private “pure” household, particularly kitchens where most domestic work is located. Caste reinforces these notions of purity and ‘hygienist’ arguments that vilify the poor and disenfranchised as ‘dirty,’ ‘unclean’ and ‘uncivilised.’ More recently, media demonisations of the poor, and especially domestic workers has amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic with many marginalised communities without the access to safe healthcare and information labelled as carriers of the coronavirus.

Also read: COVID-19 Lockdown: Domestic Workers And A Class-Caste Divide

Moreover, domestic work is often physically demanding. Though the work setting mimics an upper-class household, work takes place without fans and ventilation. Many a times, cleaning work involves constant bending over and stretching. As physically arduous periods can be for all kinds of bodies, working in a setting where breaks are forbidden further results in young domestic workers making the choice to stay home during menstruation. However, the opportunity cost of absence is high. No regularised pay means that domestic workers are paid only for the days they work. Taking an additional (assuming the least of one day period leaves) leave seems like a luxury.

Perhaps, the most significant aspect of this discussion is the massive period poverty plaguing India. Two hundred rupees per day (around ₹6,000 per month) is an inflated wage for Indian domestic workers. Compare this to the price of a cheap 12-pack of sanitary napkins—at least ₹100. It’s true that cheaper and reusable alternatives are prevalent, but their percolation is localised. More than 70% of women and girls in India still have no access to safe menstrual products. Period poverty is aggravated by COVID-19 as many workers lost access to sanitary products through their daughters going to government schools or factory shortages.

It is worthwhile to emphasise that menstruating domestic workers’ experiences are particularised by the constant segregation during periods outside of the workplace, and the week(s) of bleeding.

For instance, there is little to no access to bathrooms to change pads in an employer’s home, unless you are a live-in domestic worker in which case they might have a separate bathroom. Public bathrooms for women are in near unusable conditions. Employers cite veiled (and explicit) casteist reasons for denying toilet access to domestic workers. Reasonably, toilet inequitydiscourages women to show up to work on their periods.

How Do We Imagine Period Leaves For Domestic Workers?

Many domestic workers prefer not to incur the costs of something as luxurious as a leave. And that too, every month. Menstruation products are expensive enough to delay purchase or sell off for essential items from food to school fees. Period poverty implies two things, if period leaves do not exist. First, that leave without pay becomes inevitable and the second, that no leave is taken at the cost of using hazardous methods for menstruation management.

Period poverty complicates the question of period leave. What good is period leave in itself (sans other measures) when unsafe menstruation practices persist even without it? Beyond recognising this complication, the call for period leave is parallel to calls for barrier-free access to menstrual information and products.

Besides period poverty, casteist segregation and regressive taboos surrounding menstruation limit domestic workers’ access to the workplace in the first place. The perpetuation of these ideas results in pushes to bite the harm of not working on periods, and hence, not being paid. Formalisation of the sector, centered around caste justice and labour dignity allow for constructive policy

So, imagining period leaves fro domestic workers requires a comprehensive framework to create baseline workplace equity. Regularising pay represents a one such possible solution besides provision of menstrual products. Other such solutions include increased wages, social security in the form of governmental support, protection and redress from sexual violence and harassment at the hands of employers, .

There have been long-standing governmental efforts to include domestic workers in the ambit of regulated sectors, however, no national policy exists. Seven states have minimum wage policies and two have welfare schemes for domestic workers although many seep through its purview. Much work is to be done at interpersonal levels too. It is important to emphasise that domestic workers individually and collectively (through bodies like informal and formal unions) have voiced their demands for better pay and protections. Undeniably, this advocacy reveals the need for holistic transformations to the domestic workers’ conditions. Only when those base working conditions are promised, can we meaningfully talk about paid menstrual leaves for domestic workers.

Also Read: Let’s Talk About Period Leave for Tribal And Dalit Women

Conclusion: Room to Bleed?

Periods are not fun. They are worse when they occur in a workplace that invisiblises, degrades and profits off one’s labour—enough for absence or rest to be too costly while denying the tools for safe menstrual experiences. While generally, period leaves foster equity within the workplace, they are incomplete without efforts to destigmatise menstruation and rest, and value domestic work as legitimate work. On that note, period leave for domestic workers involves much more than negotiating or regularising pay. It constitutes systemic assurances that battle period poverty, lack of social security benefits, casteism within homes and toilet inequality.

Only when we can meaningfully mitigate the unique inequities in the informal sector, can we envision room for domestic workers to bleed without discomfort, alienation and precarity.

Featured Image Source: The Delhi Walla

About the author(s)

Sajneet is a History nerd who loves to bicycle.

This is a serious issue which has been ignored by Government as well as the Civil society,

Why all wrong tactics are tested on women’s bodies, family planning should be now a must for men and not women.