In this article, we analyse our heterosexual and monogamous relationship within the permeable isolation provided by a campus and the effects of a spatial transition and a global pandemic on the same relationship. We speak of a seemingly personal experience that we presume to be relevant to a wider spectrum of individuals at this time.

As mainstream cinema and pop culture (transcending linguistic and cultural borders) has romanticised “campus life” so much so that digging for cause and effect has become futile, let us begin by acknowledging that “college” is one of the earliest and most profound of changes we go through as we mature into independent adults. Living in a culture that unfailingly fantasises over romance and campus life interchangeably, yet is collectively uncomfortable in pursuing/realising these romantic relationships (cue Lajjo and Simran in Dil Wale Dulhania Le Jayenge), individual aspirations and sexuality for the young adults are often manifested through a “dual life”—a performance of character—one that is socially accepted (by immediate family and friends) and the other driven by individual needs and aspirations.

This ‘dual performance’ or in other cases, the shunning of one prerequisite performance is often marked by one’s pseudo-independent life in college. Being on campus and away from home enables an optional segregation of these dual lives.

The most common factors that affect relationships inside and outside of the physical bounds of hostel/campus are often hostel curfews (or the lack thereof), campus gate timings, visitor restrictions both on campus and hostels, tenant rules that prohibit certain activities and most importantly, academic-professional-social commitments.

The most common factors that affect relationships inside and outside of the physical bounds of hostel/campus are often hostel curfews (or the lack thereof), campus gate timings, visitor restrictions both on campus and hostels, tenant rules that prohibit certain activities and most importantly, academic-professional-social commitments.

Whether being in a physically proximal relationship or in a long distance relationship while on campus, since there are preordained schedules to adhere to, we schedule meet-ups and calls for when we are “free”. But beyond the free-will of students, are explicitly sexist and orthodox hostel timings for most if not all colleges, on-campus student accommodation and even private housing in India. As a result, students often resort to sneaking around and faking parental permission for night-outs in order to travel and stay outside.

The pandemic led to a closure of all these institutions urging and often forcing students to move out of these shared spaces and into their parents’ homes. But in case of older and monetarily independent students (which is rarely the case with most undergraduate students and many postgraduate students in India), most of them chose to stay in their private housings.

Being at home and in close proximity with immediate family members resulted in most romantic relationships turning into ‘Long Distance Relationships’ by default. Long distance relationships as such are not so new a concept and a quick google search would lead one to a plethora of content that ranges from cheesy gifting advice to empathetic forums that predate the pandemic—intending mostly partners of military persons and people in ‘online’ relationships.

Like in most long distance relationships, today too when physical distancing is all the more crucial, tactile communication has been bridged (quite unfulfilling) by technology. As privacy in physical spaces at home are meagre, more and more communication and sexual activities occur online and virtually, performed in bedrooms and bathrooms. But what is peculiar to the Indian context is the discomfort and oftentimes secrecy when it comes to sharing details of one’s romance/sexuality with family members.

Like in most long distance relationships, today too when physical distancing is all the more crucial, tactile communication has been bridged (quite unfulfilling) by technology. As privacy in physical spaces at home are meagre, more and more communication and sexual activities occur online and virtually, performed in bedrooms and bathrooms. But what is peculiar to the Indian context is the discomfort and oftentimes secrecy when it comes to sharing details of one’s romance/sexuality with family members.

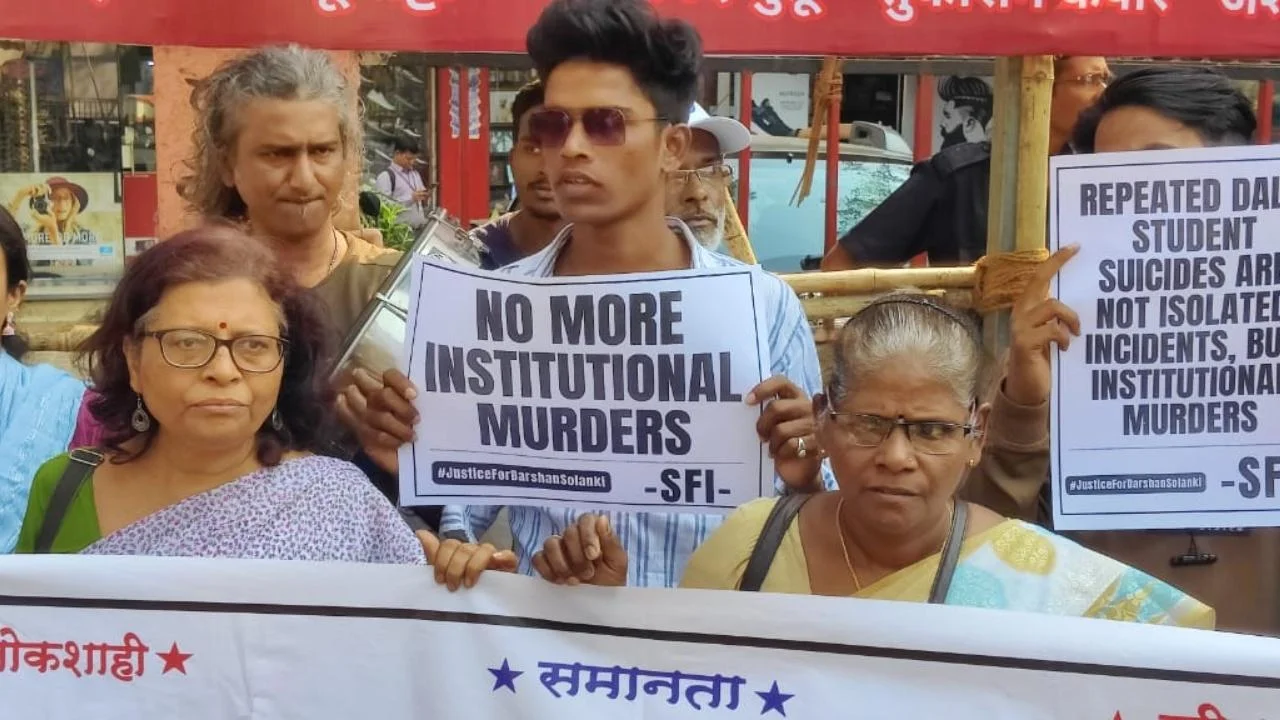

And it is this omnipresent stigma surrounding premarital sex, homophobia and persecution for so called “dishonour” of the family’s blatantly castesit hypergamous ( Hypergamy : marriage into an equal or higher caste or social group) “values” that breed reluctance to be open about love and sexuality with one’s immediate family/parents while home that in turn leads to a sense of secrecy—double life that we discussed in brief, earlier. And in our cases, these dual realities today transcend time and space with one being physical and the other digital.

Also read: Exploring My Sexuality And Experiencing Love: Memories From My Beloved Campus

As our relationships with most people these days in general are long distance in nature, facial expressions, accents and colloquial expressions have been replaced by emojis, acronyms, and memes. Auto correct and dictionaries constantly modify our written language, in turn our perceived identity. As we shift from a real-time relationship that is sustained in co-inhabited physical spaces, do our identities change too as technology bridges the jarring gap?

While we can check social media in the middle of a conversation unbothered of judgement in the privacy behind the screen, have our attention span dwindled? What does undivided attention mean anymore? How do we readjust ourselves when we go back to a life where ignoring a chat or muting a lecture is not possible? Do we tend to be more evasive in our long distance relationships now that it is easy to?

Without pheromones doing their magic in stimulating sexual activities, we find ourselves relying more on routines and excuses to perform them. The act of ‘foreplay’ is now the act of initiation through ‘sexting’ and the exchange of private pictures. The colloquial usage of “dick/pussy appointments” now bear a meaning quite different from the initial definition with stress on the ‘appointment’ part of it. And as almost all of this communication is online, we now encounter the dilemma of digital privacy.

As a sexually repressed society, people have relied on pornography for sexual release since forever. Now that people have more private time and are coping with fears and anxieties of isolation and death, statistics show that consumption of pornography has undergone a pandemic surge. Not only are some aspects of this problematic but also cautionary in nature as alarming amounts of content arises from non-consensual and illegal recording/sharing/manipulation.

Also read: Banality Of Patriarchy And How It Thrives In Our Campuses

Maneuvering through the lack of security in private digital content transmission and the blatant ignorance of the same results in an additional layer of apprehension to already strained relationships. Wanting a safer medium for exchanging private messages and content without fearing an unexpected breach of privacy has become more universal a need than before. Discourses on consumption of ethical porn and cyber safety are more ubiquitous than preceding times.

As humanity is grappling with psychological and sexual repercussions of the pandemic while technology is the only means for intimate connection, it perhaps reminds us of our mortality and in turn reminds us to reach out to those relationships that matter most to us. Without “campus” boundaries to curate the people that surround us, as we confine ourselves in a bubble different from the “academic” one, we begin to look inwards and dwell on our identity and sexuality while rethinking our relationships with ourselves and others.

Geethika is an undergrad student at the National institute of Design, Ahmedabad, specialising in Exhibition Design. When she is not speculating a feminist neutopia or fuming about gender issues, she paints, dances and obsessively stuffs fallen flowers into her hair. You can find her on Instagram and LinkedIn.

Vivek is pursuing his masters in Product Design at the National institute of Design, Ahmedabad. He is a designer/digital artist/engineer who is also a passionate storyteller and a motorbike junkie. You can find him on Instagram.

Featured Image Source: New York Times