“Between the ages of 3 to 7, I made some beautiful connections with many things and beings,” says Lipika Singh Darai.

“I had a deep bonding with a bird, I was very attached to a huge rose flower creeper climbing on to the terrace. I used to be so worried when it rained, because all the collected rain water from the terrace would fall on the rose creeper…

“… These and many more connections are extraordinary for me. Because these happened at a time when I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t know what my ‘self’ was; my gender, my identity…nothing… So I keep on visiting these connections to be able to negotiate with the outer world with a sense of compassion and they have, I think, formed my inner self,” she says.

Lipika Singh Darai is a filmmaker from Odisha and have made several independent films in Odia. She studied Sound Recording and Design at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune. She has won four National Awards–three for film direction and one for sound recording and mixing–which she received while she was still at the film school for her second-year project.

Lipika Singh Darai’s first non-fiction film Eka Gachha Eka Manisa Eka Samudra (A Tree, A Man, A Sea), made just after she completed film school, won the National Award in 2013 for Best Debutante Director in Non Feature section. She specially notes her brief association with the late filmmaker Mani Kaul as decisive in her taking the final step to make the film.

This article seeks to loiter through the universe Lipika Singh Darai has created in her films and interweaves her with her own reflections and observations on her personal journey, memories, aesthetic and politics.

Also read: Feminism and Film-making: An Insight Into Indian Filmmakers

This article seeks to loiter through the universe Lipika Singh Darai has created in her films and interweaves her with her own reflections and observations on her personal journey, memories, aesthetic and politics.

Eka Gachha Eka Manisa Eka Samudra (A Tree, A Man, A Sea)

Eka Gachha Eka Manisa Eka Samudra (A Tree, A Man, A Sea) explores Lipika Singh Darai’s relationship with her music teacher/guru P K Das in Odisha, searching for him in people, memories, objects, roads and a land . “As I learnt sound recording, I thought at least I could record his voice and keep it with me. Because he had almost no recordings of his voice. He was very old. When I was six, he was sixty. There wasn’t any plan for a film. The process of looking for him became a film.” she says.

The film clearly signals a personal aesthetic that Lipika explores and extends in her films that followed this. There is an intimacy to her films that comes not just with images and sounds, that constantly evoke an inside and an outside, but also through her poetic voiceovers. The voiceovers in all her films are always to be plugged into the political, while still remaining personal.

The film exudes a deep pain that comes only with grief of a loved one. That irreconcilable loss which we make up with the feelings of presence that the loved one offers even after their passing. The presence is invoked in as much as his only trace–the guru’s singing recorded in an old cassette, as much as his wife listening to it and his grand-daughter with such maturity and compassion trying to console her grandmother, with an explanation for his absence.

That brings me to another girl in the film. A small girl in the old music class where Lipika Singh Darai had learnt music too, with her guru, being chided by her music teacher for not practising, looks into the camera, into us, with hurt, a piercing glance, that will not leave us for long. As much as the film reminds us of a man who lived on a land which was once a sea and his passion for music, the film is also about the people around him, especially his wife and these girls.

Dragonfly And Snake

Dragonfly and Snake is a visual essay written, directed, edited and recorded and sound designed by Lipika Singh Darai. It takes the shape of a personal exchange between Lipika and her Aai (her grandfather’s sister). The film, mostly, runs through a split screen with two different images running on each half of the screen, accompanied by the reflections of the filmmaker and conversations between her and her Aai.

The split screen seems to simultaneously invoke the inside and the outside aurally and visually. A moving train, vessels on racks in a kitchen, electric transmitters, construction work and workers in Mumbai, the filmmaker’s hands, making art on paper with splattered paint to eventually emerge as a colourful butterfly on paper.

This invocation of artistic expression and creation is also foregrounded with the filmmaker’s sound recordist role, where images are often accompanied by commands which are said by the recordist before a sound is recorded on set. The split screen in the film often shows images of the inside and the outside, but is also simultaneously searching for some symmetry, be it in shape, colour or texture. It is a split screen that invokes belongingness and alienation at the same time for the filmmaker. As is in Lipika Singh Darai’s other films what draws us so intimately into these everyday images and sounds, mostly in the city, is the filmmaker’s poetic narrative.

“My maternal village was 50km away from where we live and that is where I spent most of my summer vacations. In my film Dragonfly and Snake, I mentioned about my grand aunt. I spent a lot of time in the village watching my aunt and farmers farming very closely. I learnt how paddy cultivation was so difficult yet connected to our lives just as the bloodstream in our bodies. How everyone was so close to nature, they understood seasons the way we would never be able to ..They spoke to trees, spoke to birds, animals. The way I see things, the connection or the disconnection of it, forms the exterior of my expression. And the memory, the feeling of it, the senses I keep close to my self form the interior. The constant communication between the two could be seen in my films maybe,” says Lipika Singh Darai, reflecting on her unique aesthetic.

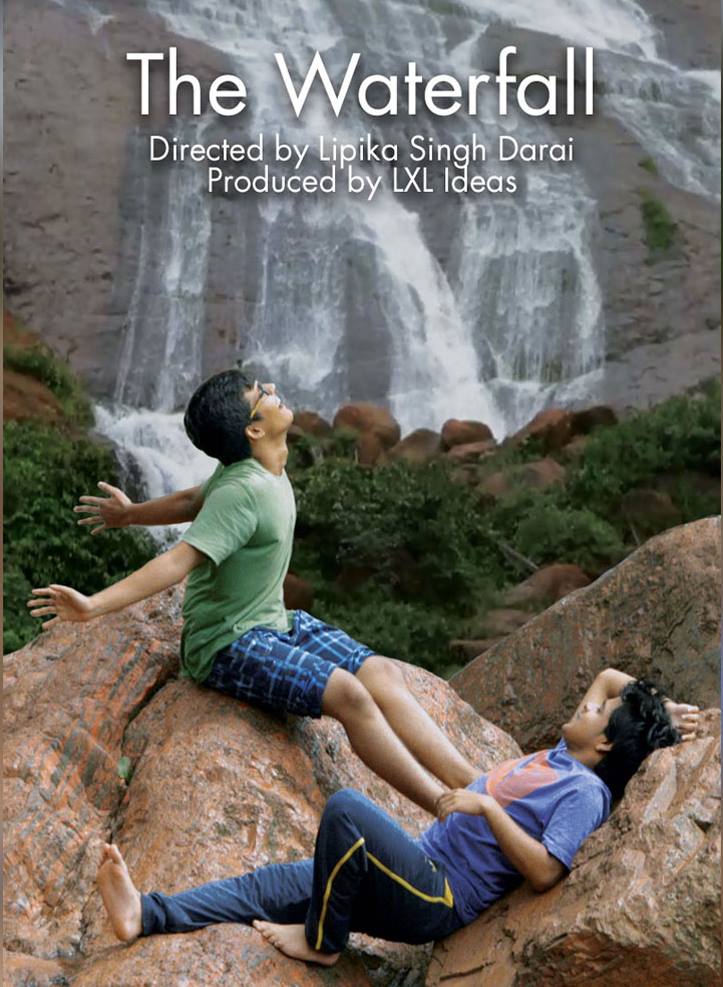

The Waterfall

The Waterfall is a short fiction film written, directed and edited by Lipika and produced by LXL Ideas under School Cinema project, intended for children. She won a National Award in the Best Educational Film category for The Waterfall in 2017. Again, The Waterfall draws us in with it’s melancholic and sensitive voiceover, this time it is of Karun, a teenager boy from Mumbai visiting his loved ones in a town in Odisha.

The film starts with Karun’s dream of a river taking over his city as he narrates it to his friend Nilu on their way to the waterfall in the forest, near to Nilu’s town. They spend time near the waterfall, allowing the viewers to take it in too, the serenity and silence nature quite often offers, and perhaps is offering the teenage boys that for the first time in their lives. The waterfall and the journey through the forest is dreamy when it cuts to the realities of the town by night, giving a jolt to our senses.

The film progresses like a stream, free flowing, like the thoughts of Karun. He feels deeply for the adivasi communities of the forest who are struggling to retain their land against a MNC that is slowly killing the waterfall. The forest invokes empathy in him and Karun is affected by a sense of loss by what is happening around the waterfall. He also feels for Nilu’s sister who is going to be married off. The internet tells him what the adults hold back about the company and its consequences.

There are familiar logics to the company’s exploitative tactics: ‘development’; ‘these people are too lazy, possessive’ etc. as opposed to the dreaminess of the waterfall and its healing nature. The film ends with Karun back in the city, with a shot of the water bottle he carried in his adventures to see the waterfall in the forest with Nilu. It ends with his voiceover–Karun has returned more aware and mindful. The final sentence and its poignance leaves an ache in the heart: The bottle now carries 500 ml of Mahanadi (the river).

“I grew up in a few villages and small towns in various parts of Orissa. I forced my parents to send me to the school when I was three. We were in a small town in Sundergarh district. The waterfall, Khandadhar, in my film is in that district, and I remember people talking about it .Of course I didn’t know that I would one day make a film on it. My primary standard one was in a remote village in Mayurbhanj district…”

“… From that place I remember a few huge trees: tamarind–people thought it had ghosts; mango–around which we used to play and put swings; pipal tree–was just in front of our house which could bend and touch the ground during storms; bamboo bushes–the sound of it; the only doctor; a Kali goddess murti–people thought she was alive; how my sister was born in our own house; storms were scary as our house wasn’t concrete; and a few friends who taught me how to catch a snake. No memory of teachers. The primary school was in a bad shape. My father got transferred to Baripada, a bigger town which was one of the cultural hubs in Odisha. I did my schooling for eight years there.”

Some Stories Around Witches

Some Stories Around Witches (2015) is a hard-hitting, sensitive non-fiction film by Lipika Singh Darai on the issue of witch-hunts persisting in many parts of Odisha. Some Stories About Witches has a structure that offers ingeniously placed surprises at many a places and is edited by Lipika Singh Darai herself.

There is a section in the film where the filmmaker is going to meet one of the protagonists in the film: Niru. When it is time for the filmmaker to meet Niru who has been imprisoned for beheading her sister’s mother-in-law (thinking that the woman is a witch) and is now out of jail, we still do not get to see Niru.

Instead Lipika hands over the camera to Niru and what we see on screen is photographs and footage which Niru shoots. After Lipika teaches Niru to use the camera, we see Lipika on screen, through Niru’s eyes. That whole sequence is a hard-hitting lesson on self-reflexivity and sensitivity. We see Niru in the beginning of the film as a blurred figure at the beach. Later we see Niru through the images she has made and in her interaction with Lipika, a friendship they have forged through the film. And it is only later, we hear Niru’s story, not seeing her face, but her hands speaking.

In the film’s introduction, a man tells the filmmaker about how he has seen witches coming together in the night. Lipika’s father is hospitalised and there are anxieties in her family about a possible curse. A sequence which shows scan reports and photographs from the hospital. Lipika’s melancholic voiceover is honest, sensitive and reflective. At the same time, her voice intervenes with the narrative. It at once places her as part of the world inside the film as well as sensitively outside wondering about Moumita’s education or clearly stating at the start of the film: I am looking for humanism in these stories.This is what Some Stories About Witches achieves as well.

Without exoticising the cruelty of the circumstances, with its melancholic voiceover and texture, it beckons towards the sadness that follows these situations, created by oppressive and unequal structures.

Some Stories About Witches carefully dissects the insensitivity of the mainstream media reportage of the issue. File photos and footage point to the cruelty to which the coverage subjects lower-caste bodies and minds to. This film in that sense in an antithesis to media coverage of the issue until then.

Another surprise awaits us in Chapter 3 of the film. Chapter 3 is titled Chicken Curry and talks about a family ostracised by a whole village for having cooked a chicken curry on New Year’s eve, supposedly breaking a belief surrounding a ritual in the village. The filmmaker intervenes with this issue, trying to negotiate with the villagers to accept the ostracised family.

There is a sequence where the camera and Lipika Singh Darai are mediators in this discussion between the villagers and the family. That is when her voiceover informs us of her personal investment in the need for a resolution: Her mother’s family was similarly ostracised several years ago until they paid up a large sum, following the demand of the villagers.

“With Some Stories Around Witches, the involvement was deep and difficult. I was making a film on a very complex devastating social issue, and there were people involved for whom I felt the most responsible as a filmmaker, and also as an individual, who was engaging with them and their lives. As I am from Odisha, I speak Odia; I can also understand Ho and Santhal languages a bit; I understand other dialects too; I have lived in the villages; I have a reasonable idea about the culture, so I could connect to them as my people. When I was with them, I had to be one of them, listening and trusting them them. For me, my involvement is the actual film. The film that I make, is just an extension of it. May be that is how I was an insider to the film. But the truth was, I was also an outsider.”

“I remember when we met the woman who was tied to the electric pole, I didn’t ask her any questions. She was apprehensive of us initially. But through us, she came to know that she was innocent. She thought the police case was on her and her husband because people thought they were witches. Slowly she opened up and talked about herself which we see in the film…When we returned she walked a bit to see us off. And clumsily and gradually lovingly, she hugged me. She didn’t say anything.

Her smell was just like my aunt’s. The smell of a village, the wood fire, the people and their lives. It remained with me as a strength as well as a deep pain.

“… To be able to portray her and many people like her responsibly in a film, when they become a part of your “personal space” needs a hell lot of emotional strength. Editing the film hence was a tough task…”

“… How much can a filmmaker intervene in a character’s life while filming was the main thing, which bothered me throughout as an insider, and I kept on asking to stop shooting. As an insider I saw things, as an outsider I could reflect on what I experienced and make a film”, says Lipika reflecting on the process of making this rather difficult film.

Like in the other films, Lipika Sigh Darai’s friend and long-term collaborator Indraneel Lahiri is the cinematographer. In fact, Indraneel and Lipika were the only crew members of this film, as they wanted the shot to be intimate and without any external intervention.

She specifically remembers his support in both of them were shifting to Odisha from Mumbai when no one approved of it. She remembers the wait before they finally found work upon returning.

Living In A Divided World

Talking about her Adivasi identity, Lipika Singh Darai says: “As a child I was very aware of the fact that I was an Adivasi (from the Ho tribe). I could even speak my mother tongue “Ho” a bit . But before you get a chance to understand and appreciate your community, the society tells you in many spoken and unspoken ways that ‘this is the identity you need to hide. Being from a Scheduled Tribe is nothing to be proud of.’ I didn’t understand it thoroughly as I child, but I have seen how we were encouraged to learn Odia. In fact Odia became my first language, and I became so good in Odia that I make films in Odia. We didn’t speak Ho at home.”

“I have faced discrimination and it remained with me, for a long time. But eventually I tried my best to not give any chance to anyone to demean me as a woman or as an Adivasi woman.

Lipika Singh Darai recounts several instances where people discussed about her and her cultural virtues that were desirable, only to note in the end that “she was a tribal”. When she moved to the city, she faced a different form of discrimination, where sometimes, liberals exoticised her looks and identity of being an Adivasi.

But Lipika says the worst insult she faced was people attributing her winning National Awards to her adivasi identity! It is as if any amount of merit for a person with an Adivasi or any marginal identity is just not enough merit for the Brahmanical society that obsesses over merit.

Also read: Women And The Challenging Art of Documentary Filmmaking

“Yes , the world I am talking about does exist. We all know that. And I live in this divided world.”

“When I generally introduce myself, I say that , ‘I am Lipika’. I don’t say , ‘I am Lipika. I am a woman.’ “

“I say that, ‘I am Lipika, I am a filmmaker’. I don’t say ‘I am Lipika. I am a woman filmmaker’.”

But in places when I mention that I am a woman filmmaker, I try to underline the something important, in the same way as when I say “I am Ho, or I am from Ho tribe”, she says. Now that Lipika has a space where there are thousands of people listening to her, she chooses to identify publicly as a member of the Adivasi community. She explains that we are all formed of multiple identities.

“Filmmaking helped me to create this space for me and made me a person who is ready to question, introspect and change…An Adivasi is not the only identity I have. We all should be able to live with all our identities we have in terms of caste, gender, sexuality, religion, etc. without any discrimination,” she says.

Lipika Singh Darai’s films are important in not just articulating her own perspectives and politics, but also as perhaps the only female voice that reaches us from Odisha through cinema, until now.

It is very difficult to be an independent filmmaker in India. There are few opportunities to find the resources to make films, especially non-fiction documentaries. It is inspiring to see Lipika Singh Darai make films, despite the struggle to do so.

Her films are important in not just articulating her own perspectives and politics, but also as perhaps the only female voice that reaches us from Odisha through cinema, until now.

Some Stories About Witches can be watched on the PSBT Youtube channel.

Sudha is an independent researcher and filmmaker and currently lives in Kochi, Kerala. She can be found on Facebook and Instagram.

All pictures as provided by the author.

It takes time, energy and imagination to travel with another person’s work. Lipika is one with strong authorial voice. The mutuality is so palpable in Sudha’s writing. It’s beautiful.

Sensitive, lyrical writing…Kudos to the filmmakerr who inspires such a writing that is at once poetic and political…makes me want to watch all of Lipika’s films.Thank you Lipika and Sudha..