TW: Caste-based atrocity, rape

Two weeks ago, four upper-caste men in Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras gang-raped and assaulted of a 19-year-old Dalit girl. She succumbed to her death on September 29, 2020. Amidst claims by the Hathras SP Vikrant Vir that there was no sign of sexual assault of the girl, we woke up to the news of how the UP police rushed to burn her body at 2:30am on September 30. In the tweets below, we find how the UP police forced the parents to cremate the body of the victim.

At one point, a cop is also heard saying “Aur aap log maaniye ki aap log se bhi galti hui hai” (You will also have to accept that you made a mistake too.)

Also read: How Is Rape Culture Related To The Notion Of Women As Carriers Of Family Honour

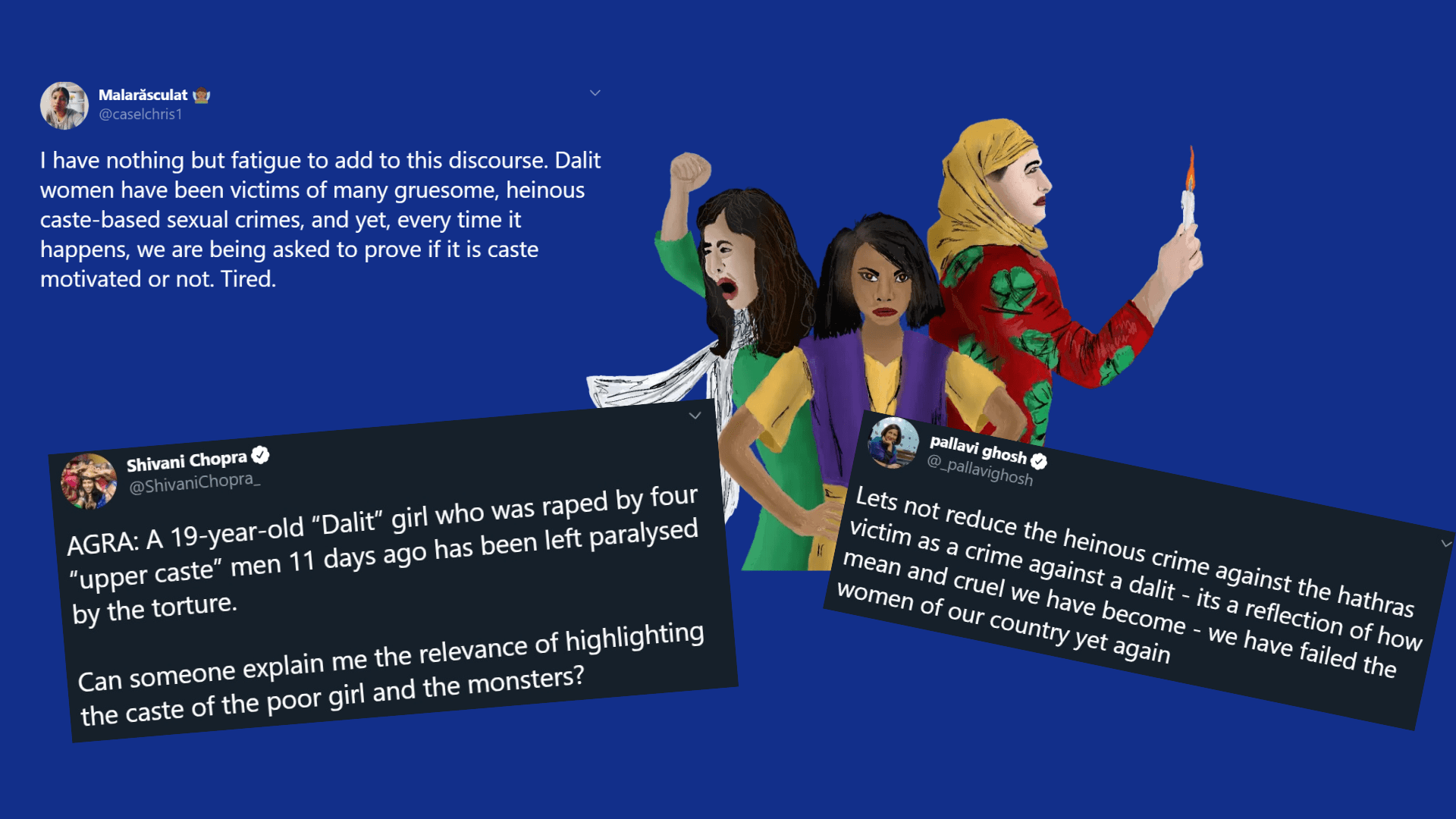

On Twitter, meanwhile, many were of the opinion that the caste of the perpetrators and the victim was irrelevant.

This is only one of the latest incidents underlining why an intersectional approach to feminism is of utmost importance. In a country like India, where several multiple realities coexist because of complex social structures, hierarchies, and systems, to achieve equality of the sexes is a complicated task.

With the subsequent waves of the feminist movement, the axes of caste, class, sexuality, physical and mental disability, ethnicity and the overlapping systems of discrimination are being better understood, but the ground reality is evidently such that we are miles away from where we need to be

Intersectionality, defined by Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the complex, cumulative manner in which the effects of different forms of discrimination combine, overlap, or intersect” is but the backbone of feminism. In order to cater to the multi-layered aspects of gender-based discrimination and understand how patriarchy permeates through these layers, feminism must be inclusive of all lived experiences and cognizant of all standpoints within the feminist movement.

Intersecting discrimination needs to be comprehensively examined to understand the flaws in our vision of gender inequality. When one thinks of gender-based violence, the experience of Dalit women is invisibilised and even normalised, owing to their status of being at the bottom of caste and class ranking.

Intersecting discrimination needs to be comprehensively examined to understand the flaws in our vision of gender inequality. When one thinks of gender-based violence, the experience of Dalit women is invisibilised and even normalised, owing to their status of being at the bottom of caste and class ranking.

While there is an uproar in the online world with women reclaiming agency and autonomy over their bodies, a grim parallel reality exists in several pockets of our country where Dalit women and their bodies are seen and used by upper caste men as a tool to exert power and maintain hierarchies, furthering oppression.

The lived experiences of Dalit women cannot simply be attributed to their social standing as determined by their economic status or gender. It is the complex web or intersection of these modalities that makes their suffering unique, demanding concerted efforts and affirmative action to uplift them.

The #MeToo movement, albeit a much-needed campaign, was led by upper-class and upper-caste Savarna women even though it was Raya Sarkar, a Bahujan law student, who initiated the movement in India by compiling a list of alleged sexual predators in Indian academia. Her contribution was recognised by the feminist movement, but was soon forgotten. It ended up being a savarna women-led movement, with the voices of Dalit women silenced and underrepresented, making it an incomplete movement at that.

The inconsistencies in the lived realities of different women, especially those from the marginalised communities led to a split in the feminist movement in India. Dalit feminism was initiated when Dalit women recognised that their struggle emerged from the nexus of caste, class and gender, termed as the ‘Triple Alienation’.

The oppression faced by Dalit women is multifaceted; they are oppressed by men not only from upper castes but also from the Dalit community. The caste system is such that there are hierarchies within lower castes as well, with certain castes being higher up than others.

Untouchability is rampant in India, so much so that our domestic help who cleans the toilet doesn’t and cannot cook in the kitchen. The caste they are born in assigns them a particular line of work, which they must stick to. And even though many woke individuals argue that “caste doesn’t exist”, caste remains an integral marker of the social fabric of our nation.

The way Dalit history and the voices of Dalit women have been erased from the mainstream media, books and Indian literature, speaks volumes about the neglect faced by the community at large, especially within the women’s movement.

The way Dalit history and the voices of Dalit women have been erased from the mainstream media, books and Indian literature, speaks volumes about the neglect faced by the community at large, especially within the women’s movement. Even as news channels and anchors put together panels to discuss and condemn the Hathras gangrape, Dalit women’s voices were largely amiss.

Christina Thomas Dhanraj, writer and the co-founder of Dalit History Month Collective, also commented on the graphic narrations of the rape of the Dalit girl.

Can we then imagine using the same set of actions and policies to benefit women having such stark differences in their realities; can we assimilate the differences in discrimination experienced by women from the myriad subgroups within the larger population?

Violence is also invisible when it comes to transgender or sexual minorities, since conversations around gender have majorly been ‘women-specific’. Even though these groups are constantly harassed, mistreated, victimised, misunderstood, and their identities denied, especially for those who belong to lower class and castes, the treatment of gender-based violence against women of these vulnerable communities remains inept, exposing cracks in our policies, legislation and social structures.

The stigma and intolerance that sexual minorities face just for asserting their presence and claiming their identities is appalling.

Also read: Why Do Women’s Bodies Become Sites Of War, And Caste And Communal Conflicts

The instances of gender-based discrimination, if deconstructed, reveal a unique set of factors that make the experience one of its kind. This is what standpoint theory, a feminist theoretical perspective arguing that knowledge stems from social position, aims to accomplish. In other words, it asserts that an individual’s own perspectives are shaped by his or her unique social and political experiences.

The lived realities of a Muslim trans woman, a savarna Hindu woman, a Dalit girl who dwells in a small village, a queer woman with disability, are all very different from each other. There will be a common denominator – discrimination, but the nature of that discrimination varies, so do the modalities. This is the ultimate goal of feminism – to deconstruct, decode and examine the experiences shaped and influenced by one’s gender, and fill the cracks that exist to create a society that is accepting, safe and healthy for all individuals.

About the author(s)

Priyanka is an unfulfilled engineer and an MBA graduate from IIM Indore. She is a writer, interested in carving the world through her biased lens, painting pictures with heavy imagery and highlighting the mundane, often ignored, but essential aspects of life. Her latest project is The Mental Indian, an attempt to de-stigmatize mental health in India, through stories, perspectives and conversations.

This same sentiment is not limited to just movies and Bollywood music, in fact – Marital rape is STILL legal in India. It is 2020 and a spouse is allowed to repeatedly rape their partner without getting into any trouble for it. The government has come up with a variety of excuses the most perverse of which blames the illiteracy rates in India and insinuates the elimination of the Act to be detrimental.