India is striving to empower more women in the field of science and technology. The theme of 2020 National Science Day was “Women in Science”. In this essay, however, I will share my experience as a woman scientist of encountering toxic officials in a research institution. My experiences, I’d like to believe, indicate how such toxic work cultures negate the positive effect of ‘women in science empowerment’ initiatives taken in India. Not only did they make my passionate return to my vocation as a scientist difficult, they did so by also implicating me under false charges, which I managed to prove wrong.

My experiences, I’d like to believe, indicate how such toxic work cultures negate the positive effect of ‘women in science empowerment’ initiatives taken in India. Not only did they make my passionate return to my vocation as a scientist difficult, they did so by also implicating me under false charges, which I managed to prove wrong.

After clearing NET and GATE, I got a PhD from a premier institute in India. Following my postdoctoral position at the University of Oxford, I took a small career break for my children. When I came back to India in 2012, I realised that my scientific record was not enough to obtain my desired job in India. Further, family obligations restricted me to a smaller city. My extending break worried me. But I was persistent and did not want to give up just yet.

Also read: How Indian Higher Education Discourages Women In STEM

That is when I applied for women scientists’ fellowship. I obtained the BioCARe Fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) of the Indian government. Launched in 2011, the fellowship’s objective is as thus: “The purpose is to build capacities for women Scientists employed fulltime in Universities and small research laboratories or unemployed women Scientists after a career break so as to help them undertake independent R&D projects.” It is specifically constituted to bring highly educated Women Scientists to mainstream after a career break.

As an awardee of the fellowship, I would definitely say, it is a great effort by the DBT towards women in STEM.

A significant part of my time as a BioCare fellowship awardee was spent sorting out unjustifiable official obstructions created by the so-called support staff of the administration, finance and the project management team (PTM) at the mentoring institute I was posted at. This exhausted me mentally. I also had to witness instances of nepotism which further demotivated me.

However, the officials at the mentoring university/institute where I was situated created a toxic work culture for me. A significant part of my time was spent sorting out unjustifiable official obstructions created by the so-called support staff of the administration, finance and the project management team (PTM). This exhausted me mentally. I also had to witness instances of nepotism which further demotivated me.

To start with, during the course of my fellowship, my salary payments were routinely delayed. Given below is one instance:

In March 2015, the administration suddenly began to deduct tax from my fellowship without informing me. The official involved was very rigid and refused to accept confirmations forwarded from the DBT. The situation persisted till July and I had to file a written complaint at the administration to resolve the matter.

Another official who made the work culture extremely toxic for me, was the head of PTM. The DBT Order, the Sanction of the President under rule 18 of the Delegation of Financial Power Rules, 1978 clearly mandated me as the Principal Investigator (PI) of the project.

But, PTM refused to accept me as the Project Leader or PI and recorded my mentor as Project Leader or PI in official documents. It was an utter misrepresentation. Further, a scientist’s track record is demonstrated by their portfolios of publications, fellowships and funding awards. So, this move by the PTM would definitely hamper my portfolio and in general, is an injustice towards the goal of empowering women in STEM.

Further, the PTM scientists and staff attempted to belittle me in so many ways, for instance, they refused to directly interact with me, refused to provide me access to my project documents, etc. Considering the negative attitude of the PTM-head, how was I to expect any cooperation from the rest of the team?

A significant part of my time at the institution was spent to overcome toxicity and suppression. Of course, I had a great project, but how would your research ideas get converted into usable technologies, when you are fiercely driven out of track?

The toxic work culture that I was exposed to at the hands of the officials there reflected their condescending attitude towards women scientists. Such determination, if used as a fuel in the right direction, would have helped them fulfil their professional obligations as per government mandate, i.e. genuinely facilitating publicly funded research grants to achieve outputs to ensure our country shines on the global stage.

After my tenure completion, I had to write a project report, clean the lab etc. and in January 2020, I started my No Objection Certificate (NOC) formalities. I had expected for a fast and smooth process as I was leaving. But what happened was just the contrary. I was oblivious to how a specially formed “Five Men Committee of Toxic Officials” was geared up to enforce their agenda against me, by implicating me in a financial misconduct of the BioCARe project.

I still find it difficult to understand their motive.

I am a struggling, independent woman scientist, whose whole career is dependent on funding from agencies such as DBT, DST and BIRAC. A financial allegation could have ruined me entirely, including my career, my finance and my life forward. Maybe that is exactly what they were hoping for, as per their vile ways for women in STEM or should I say ‘Women in Science Oppression’?

Also read: 8 Women In STEM Who Made Their Mark In 2019

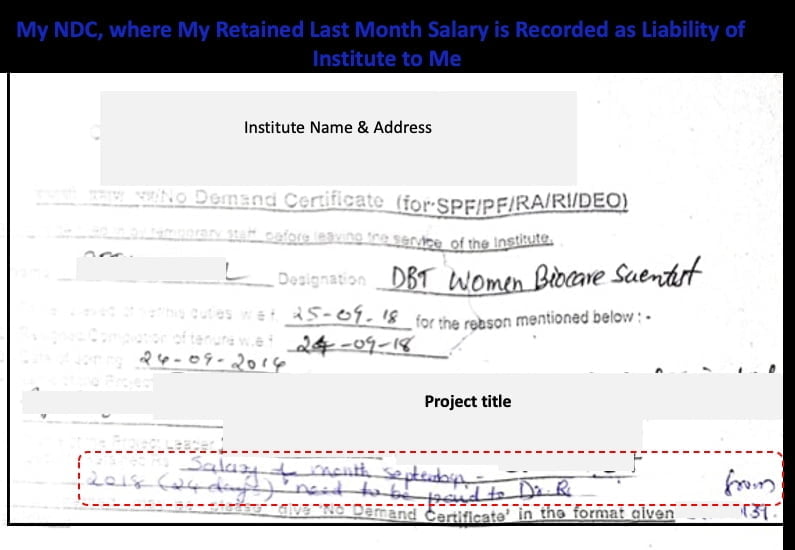

The conspiracy against me was set in motion by the FAO, who falsely recorded outstanding financial liabilities of BioCARe project as pending against my name in my No Demand Certificate (NDC), followed by the rejection of my NOC by the COA and PTM-head.

I met the FAO, but he refused to elaborate the liabilities. I resubmitted the NDC with a comment to refute the allegation, hoping things will be solved without further aggression.

But the situation started escalating. The Security Officer, suddenly became hostile and denied me entry by stating financial misconduct. Further, he also encouraged the security staff to misbehave with me.

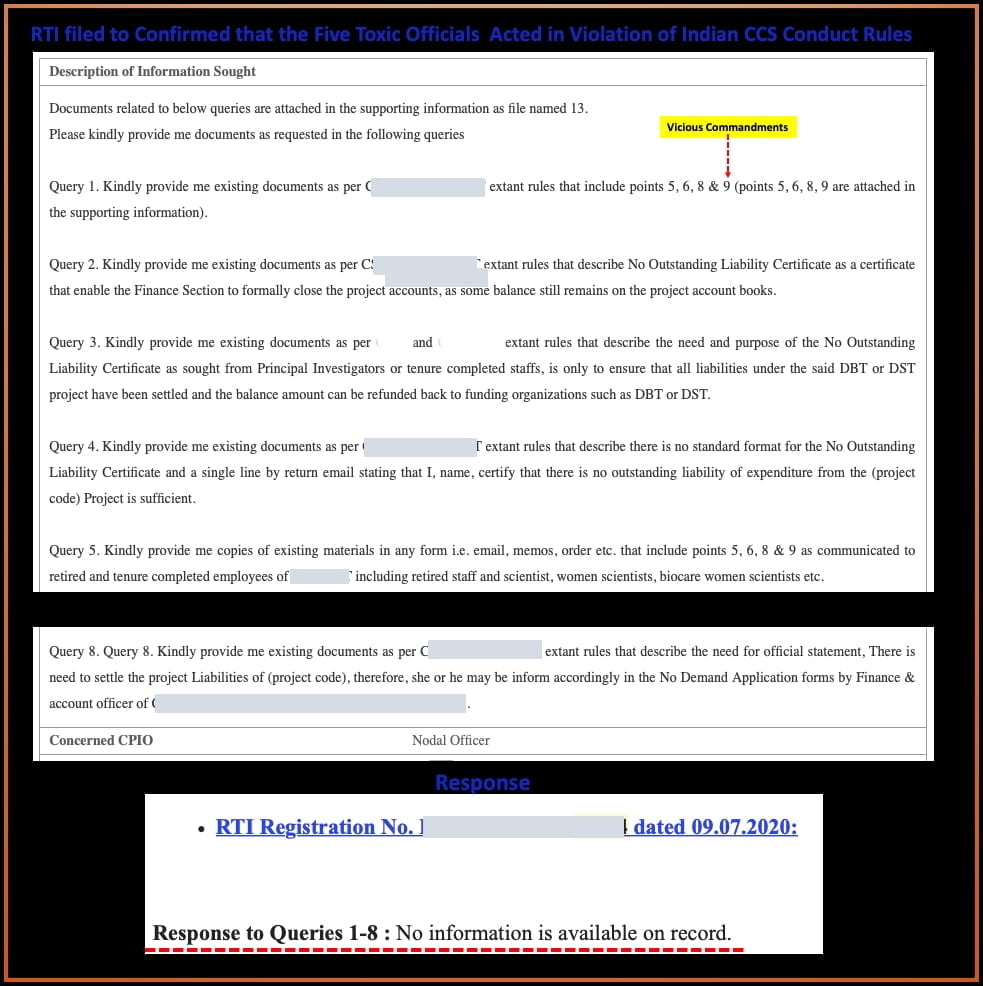

Playing his part in this elaborate scheme well, the COA delivered the “Eleven Vicious Commandments” to me via email on March 2, 2020.

Commandment-5 demanded a non-existent “No Outstanding Liability Certificate” from me in violation of the conduct rules and also declared my NDC as incomplete.

Commandment-9 introduced a well rhymed ridiculing language in their conduct rules that can be very useful in the future to target women scientists. I rarely met any of these officials and there was no need for such indecent tactics.

There was complete failure to uphold my right for equality as per Article 14 and also, a gross violation of CCS conduct rules. Of course, I filed complaints. My complaints were not even acknowledged, but my concerns instigated the commandment-11.

A Section Officer in Administration also started demanding the non-existent certificate in June 2020 again.

In a determined quest to prove my innocence, I filed RTIs in July 2020.

Responses to RTIs explicitly proved that there was no financial liability or misconduct on my project. My NOC application submitted in February 2020 was complete, as per protocol. Turns out, there was no need to submit any non-existent No Outstanding Liability Certificate.

Further in response to the RTI appeal, despite the enormous evidence, the Finance and Administration division indirectly blaming Administration for all the violation of procedures.

My RTIs forced these toxic officials to perform their duties. I received my retained wage. My NOC was given to me recently in September.

But they refused to provide a copy of my office memorandum (OM). I filed an RTI appeal and it forced them to release a copy as the response. My NOC was given to me recently in September.

A similar sentence is also added as response to RTI appeal. My pending salary is the liability of the Institute and is already recorded in my NDC as per NOC procedures.

Now with my last month’s salary finally credited to me, what I close is a chapter of harassment and emotional torture that I faced on the professional front. Though women in STEM has come to be a matter of interest from the purview of gender parity, it is also important to ensure institutional mechanisms do not belittle women in science the way I was.

Featured Image Source: The New Yorker