First you notice how they’re all poor, and then you notice how they’re all men.

Since its inception, American Hip Hop has been a forum for political activism against racial discrimination, poverty, and police brutality among other things. Over the last thirty years, it has transcended from a music genre to a complete global culture influencing lifestyle, economy, and politics. Hip Hop entered the Indian mainstream in the 2010s, coincidentally emerging alongside BJP’s rise to power. Globally, Hip-Hop has outlined the relevance as well as limitations of social identity in a multicultural nation. An arduous exercise of tracing the development of Hip Hop in India in 2000s and 2010s would lead one to G-Funk mimics in underbellies of Mumbai, the cyphers in Delhi’s parking lots, and the 50-people capacity bars in Assam and Shillong.

But in a short span of 5 years, we’ve come a long way from circulating one pen-drive with 50 Cent, and Eminem’s entire discography across the whole city. Now, Spotify and Apple Music have regularly updated playlists and charts dedicated to Indian Hip Hop. Apple Music’s The New India playlist features “MCs from across India.” While it has big names like DIVINE, Prabh Deep, Seedhe Maut, and Naezy, from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, it is interesting to observe an absence of women from these charts.

But before you notice they’re all men, you notice how they’re all poor men. An economically disadvantaged Bronx’s interaction with music is what birthed the genre in the first place, so it is no surprise that a Marxist-style class analysis never escapes any Hip Hop discourse. Understanding Hip Hop is not poetic politics, the genre equips both the audience and the creator with a stage in the public space. And it is this public space that dictates norms, and struggles.

Apple Music’s The New India playlist features “MCs from across India.” While it has big names like DIVINE, Prabh Deep, Seedhe Maut, and Naezy, from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, it is interesting to observe an absence of women from these charts.

Hip Hop : A Vice and a Political Device

In India, Mumbai’s slums have become a popular site for the emergence of Hip Hop, specifically Gully-Rap. DIVINE, one of the most famous rappers in India, opens his 2019 album’s title song ‘Kohinoor’ with “Cement se nikla gulaab, aitihasik kitaab, har hal ka jawaab sach hue mere khwab” (A rose bloomed in concrete, a historical triumph, all my dreams have come true.)

Most likely inspired by 2pac’s lyrics along the same lines, this theme seems to be rooted in a prevalent ideation of political economics that disadvantages the working class and disables them from participating in society. So when a rags to riches story is presented to an audience, it is met with overwhelming exuberance. DIVINE and a dozen other rappers like him are presented as victors against economic decay—a perfect capitalisation of class struggle sold to the masses.

So when a rags to riches story is presented to an audience, it is met with overwhelming exuberance. DIVINE and a dozen other rappers like him are presented as victors against economic decay- a perfect capitalization of class struggle sold to the masses.

But regardless of how irrelevant individual success stories are to the big picture and the structural flaws of the system, an expression of dissent against it only brings these issues to the center stage. A Tribe Called Quest’s We the People is considered the political anthem of the decade, and Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album To Pimp A Butterfly has provided the Black Lives Matter movement with most of its anthems. In India, Ahmer, a Kashmiri rapper, rose to fame recently and was signed to Azadi Records. In his track titled ‘Elaan’, also featuring Azadi Record’s Prabh Deep, Ahmer talks about the struggles of growing up in Kashmir—

Jedde border ni tappe, karan jung da elaan. Aais tabaehi manz batke, yi chu junguk qalaam. (Those sitting comfortably at home are declaring war. We are lost in destruction; this is the word of war.)

In an interview with Caravan Magazine, Ahmer cites MC Kash as one of his inspirations. MC Kash who is credited with origination of Kashmiri rap, rose to prominence in 2010 with his song ‘I protest (Remembrance)’. Over the years MC Kash has been a victim to several acts of police brutality and discrimination, including a studio raid.

Economic and political oppression should never escape a caste analysis. Although Dalit voices in Hip-Hop still need a bigger stage, Casteless Collective is a Chennai-based band who frequently raps about Dalit violence and caste based oppression. In a recent song, they talk about caste and manual scavenging—‘though it is just a quarter of a rupee, it is a government salary. So, I go around the city, cleaning shit with my bare hands.’

‘I Don’t Cook I Don’t Clean but Let Me Tell You How I Got This Ring‘

How to Sell a Woman in Hip Hop

Political or otherwise, rapper’s identities are often constructed around hyper masculinity. Gender and sexuality work together to promote the persona of the male rapper. Women want him and men want to be him. The consumer market for hip-hop is also considered to be very male-centric, meaning that music is being produced for a predominantly male audience. Hyper masculinity is promoted through a hustle culture which, when wedded with capitalism, provides for convenient marketability.

The rapper who rose from economic and political turmoil is portrayed to be now in possession of everything that can be possessed—wealth, and women. America, the birth land of Hip Hop, is also the birth land of Neoliberal Capitalism so it is not surprising to find the oppressed class trying to attain the status of the oppressor class instead of dismantling it. Much academic work has been done to understand American black masculinity and its impact on black women but since global Hip Hop is heavily influenced by America, ideas of masculinity also cross borders.

America, the birth land of Hip Hop, is also the birth land of Neoliberal Capitalism so it is not surprising to find the oppressed class trying to attain the status of the oppressor class instead of dismantling it.

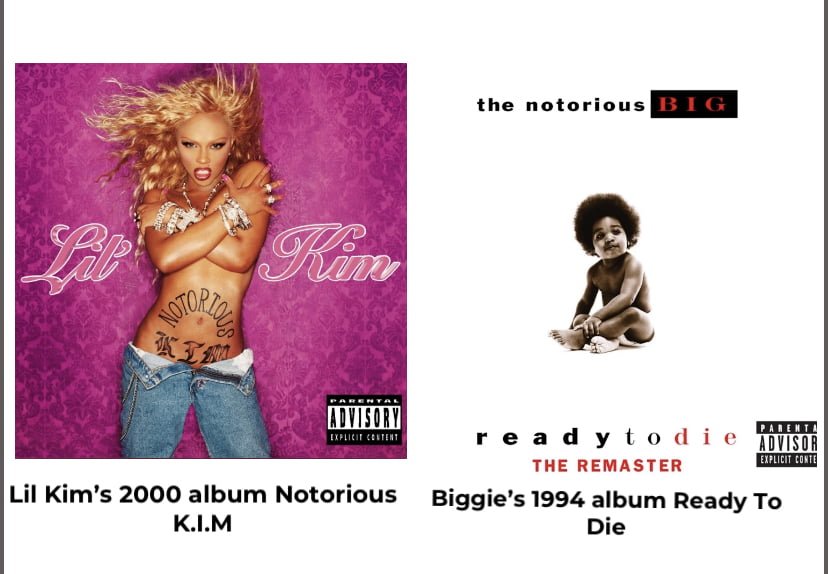

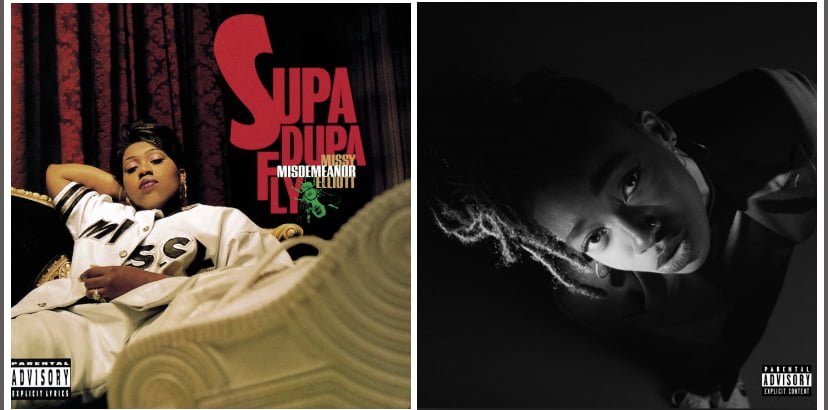

It is fairly easy to market masculinity to a male audience than femininity. However, women have always participated in Hip Hop, including the infamous Missy Elliot, Queen Latifa, Lauren Hill, and Lil Kim. Sexualisation of women through music videos as well as lyrics aid to a song’s appeal but to market women in hip hop, and as can be assessed from the recent popularity of Cardi B’s WAP, women are put in charge of their own sexualisation. Media visuals help heavily with the popularity of a song.

Thus, when we credit these songs with sexual liberation, it is important to understand that the content of the hypermasculine music has not changed, but the agents have. For a woman to be a successful rapper, being a talented musician is secondary to having immense sex appeal. Women need to cater to the male gaze, while their male counterparts are not held to the same degree of scrutiny.

In India, apart from a handful of rap artists like RajaKumari and SIRI, there are almost no mainstream female rappers. In addition to the general oppression males go through, a layer of sex-based discrimination is added to the female experience of oppression. It is thus surprising that hip hop hasn’t found a space to voice these experiences. During my research for this article, I interacted with a few industry insiders and Hip Hop enthusiasts and was disappointed to learn that almost none of them had a female artist, Indian or otherwise, in their personal hall of fame. But patriarchy is not unique to India.

Also read: In Conversation With Anti-Caste Artiste Arivu: Rapping For Equality

Women do not lack political rage or skills, they lack resources to encapsulate it and they lack a stage. When a 17-year-old from an impoverished neighbourhood in West Delhi is in a rap battle with someone in Hauz Khas’s cypher area, his sister is at home aiding his mother with household work. While this is a global phenomenon, Indian hip hop can certainly learn some lessons from the UK and America about female inclusivity.

In a Pitchfork article titled ‘Rico Nasty and The Importance of Black Women’s Anger in Rap’, the writer talks about navigating a sexist and racist music landscape and how the anger it causes is often demonised as a stereotype for black women. Rico Nasty, with her punk infused rap style, embraces this stereotype and as a result, reclaims it. In the UK, rapper Little Simz talks about her experience as a woman in the industry in a track titled Venom, “It’s a woman’s world so to speak, pussy, you sour. Never giving credit where it’s due ‘cause you don’t like pussy in power.” Little Simz and Missy Elliot serve as examples of rebelling against the male gaze, presenting themselves in a non hyper-sexualised avatar while still being a success with their male audience.

While Hip Hop in India is still in its infancy, it is emerging at a very crucial political junction. Dissent expressed via music has the power to mobilize masses. Thus, understanding how Indian Hip Hop can accommodate for political voices better and depart from capitalist glorification, sexism or other flaws that are usually associated with American Hip Hop is of extreme urgency. Because in words of Gil Scott-Heron, the revolution will not be televised, but it will be sung. It will slip into the corners of Mumbai, it’ll crawl into the bends of Assam, and its sound will reverberate in Delhi’s 200 AQI air.

Also read: Ladai Seekh Le! Ambedkarite Sumeet Samos Is Transforming Indian Hip-Hop

The revolution will be sung.

About the author(s)

Halima is a History graduate from Lady Shri Ram College for Women. She has worked with grassroots political parties as well as international organisations. Her research interests are feminist theory, foreign policy, and area studies. She is currently doing a Master's in International Relations. In her free time, she passionately advocates for Phineas and Ferb songs for Grammy's.