On a video call with my friends recently, I was struck by how much I censor myself while discussing certain subjects, when my parents are around. I noticed how vigilant I become and how consciously I sanitise my language as I speak to my friends about desire, trauma, and politics. In an attempt to create safe spaces, many of us talk with headphones on, in hushed tones or in secluded corners — We’ve become innovative in our everyday resistance. Often, ‘home’ as a space generates a constrained self — a self-surveilling unit that has to perform certain expectations even as it subverts others.

Young people from conservative family systems rely on alternate avenues – recreational, educational, co-curricular, digital etc. to explore and express themselves. The lockdown forced upon them sporadic access to many of these safe spaces which previously provided different outlets to nurture themselves outside their homes. Moreover, the different identities and responsibilities they embodied in different spaces are now cramped together in one physical space. For many, this means bargaining in new ways with the systems that fostered their constrained selves.

The lockdown forced upon young people from underserved families sporadic access to many of these safe spaces which previously provided different outlets to nurture themselves outside their homes. Moreover, the different identities and responsibilities they embodied in different spaces are now cramped together in one physical space.

Also read: Let’s Talk About Alternate Safe Spaces For Queer Women In India

There is a lack of safe spaces that affirm young people’s autonomy and curiosity. Conversations about bodily changes, sexual desires and mental health are often institutionally discouraged, pushing young people to depend on peers, older siblings, or the internet. However, these sources are not consistently reliable and can often perpetuate casteist, patriarchal or ableist notions.

Safe spaces thus become crucial for personal growth and development. They provide a secure and non-judgemental environment for individuals to explore freely and be vulnerable. Additionally, these spaces have the potential for the youth to question oppressive discourses that otherwise stifle expression and inquisitiveness. Depriving young people of these safe spaces can thus have significant consequences for their relationships, decision-making, and agency.

During the lockdown, The YP Foundation‘s Know Your Body Know Your Rights (KYBKYR) Programme, envisioned the possibility of creating virtual safe spaces for adolescents (14-18 years) from underserved migrant camps in Sikanderpur and Sheikh Sarai in Delhi-NCR.

For context, the KYBKYR imparts Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) to adolescents in Delhi-NCR, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. CSE is a rights and gender-focused approach to sexuality education that equips young people with the information they need to protect their dignity, health and wellbeing. Further, the advancement of intersectional feminist values is central to the curriculum. With this spirit, CSE gives young people information about body anatomy, puberty and the physical, emotional and social changes that come with it. Further, it also discusses topics such as attraction, consent, relationships, identities, power, violence, safe sexual practices, contraception, and abortion.

The news of the lockdown brought uncertainty for the KYBKYR team, considering how several participants were children of migrant workers, who were left vulnerable by financial instability and state neglect in the pandemic. Thus, the KYBKYR team had to be cognizant of the needs of the adolescents and the barriers that might impede their participation and affect their access to safe spaces.

Reimagining Virtual Safe Spaces

So we come back to the dilemma we started with — How can young people talk about attraction and safe sex practices while being confined to spaces that penalize these conversations? How can adolescents get answers to questions around menstruation and nightfall — answers that are rooted in evidence and not cultural stigmas? The contexts of the adolescents from Sikanderpur and Sheikh Sarai posed many barriers.

First, many participants from the two migrant camps had to struggle to get access to smartphones and a stable internet connection. Quite a few young people from marginalised caste and class locations could ultimately not afford the necessary devices and couldn’t attend the sessions. Those who could now had to attend CSE sessions on their phone screens — in their sometimes patriarchal homes — often surrounded by family members in a small space. Due to the spatial distancing protocols, young people from underserved communities might have lost a large part of their liberties and privacy due to the restrictions on their mobility.

Earlier, the act of assembling together in a physical space allowed participants to leave their homes and enter what were sexuality-affirming, participatory safe spaces. These spaces acted as an antithesis of the dominant cultures that surrounded them. With the safety and comfort of the physical safe spaces, adolescents could express themselves freely without fearing punitive shaming practices. Thus, transitioning to the online modality had to mean ensuring these qualities to some extent. The team relentlessly brainstormed novel ways of infusing this spirit in the virtual sessions and incorporated the following measures:

- The students were asked to find a space in their environment where they could speak and listen freely and where, ideally, no adult would be watching over their screens. This — instead of being a directive — was a suggestion that reinforced the fact that young people are the experts of their contexts and can suitably find appropriate areas in their surroundings whilst maintaining social distancing and other safety measures.

- The participants were encouraged to use headphones to ensure clarity. But more importantly, to make sure no one around them could listen to the sessions. Further, using audio and video features was made optional. It was left to the discretion of the students and whatever they were comfortable with was respected. The participants who couldn’t use the audio function were encouraged to use the chatbox and ask questions there. While having audios and videos switched on would be much more useful for facilitators, the privacy and comfort levels of the students were incredibly crucial for the TYPF team to safeguard.

- The facilitators also made sure to give trigger warnings before sensitive content on topics like violence, to allow the students to take breaks or leave the session if they needed.

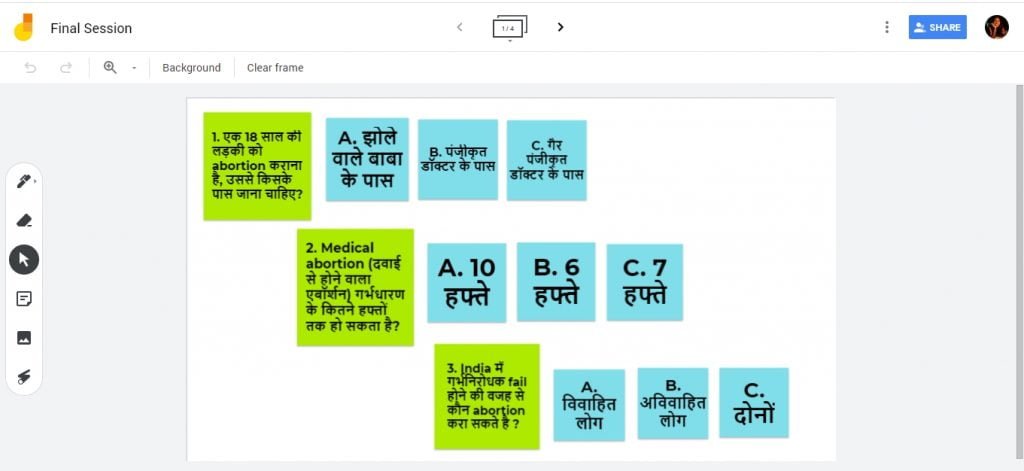

- On observing that students were displaying hesitation and discomfort around saying words like sex or condom or abortion, the facilitators labelled the options of an MCQ question as A, B, C. During revision, the facilitators openly discussed all the concepts. However, when expecting participants to respond, they asked them if the correct answer was A, B or C instead of asking them to say sex, condom or abortion. This was necessary because while in the field saying the taboo words out loud becomes a part of the de-stigmatisation process, here the learning space involved the possible presence of social actors who could reprimand them for having these conversations. This change was a sensitive and attentive response to session observations.

The trade-offs that TYPF made are emblematic of their participant-centric approach to the online transition where the contexts and needs of learners came first.

Possibilities

“समाज के बारे में, अपने शरीर के अधिकारों के बारे में बताया, वह बहुत अच्छा लगा।”

“मेरे शरीर में क्या होता है, यह सब मुझे पता नहीं था। उस बारे में मुझे समझ कर बहुत मज़ा आया।“

I had a chance to ask the participants what motivated them to join the virtual sessions each week. Everyone said that these sessions held an important place in their lives, helping them learn about their bodies and rights. Many emphasised that learning about different bodies and diverse experiences gave them new perspectives.

“समाज से जो हमे सोच मिली है, वो हमे change करने का मौका मिला है।“

Some mentioned that they reflected on the language they used to address oppressed groups like the trans community and vowed to be more sensitive. The conversations around the role of society and its policing of all that it considers unacceptable were also extremely moving and relevant for some. It provided a critical bent of mind and allowed them to see how society boxes and suppresses people. One participant said that these discussions inspired him to be less judgmental and encouraged him to talk to other people about problematic societal perceptions.

“इस से पहले हमे यह पता भी नहीं था के ऐसे sessions भी होते हैं जहाँ ऐसी बातें भी हो सकती हैं। तो हम खुद ही में उलझे रहते थे की क्या सही है और क्या गलत है। आपने हमारे doubts clear करे, सब बताया, छोटी से छोटी बात, वो बहुत अच्छी लगी हमे। नये लोगो से मिल के भी बहुत अच्छा लगा। नये दोस्त बनाने का मौका भी मिला। इतने तरह के लोग हैं और इतनी तरह की सोच होती है सबकी। आप सब लोगों को मैं बहुत miss करुँगी।”

These sessions went beyond just serving an educational purpose. The digital sessions, during the two hours, became socio-emotional safe spaces of personal and political discovery through an interactive and supportive community experience.

These sessions went beyond just serving an educational purpose. The digital sessions, during the two hours, became socio-emotional safe spaces of personal and political discovery through an interactive and supportive community experience.

When asked about difficulties, the students talked about the struggles of having to persuade parents to buy or lend them a phone. Additionally, battery and internet connectivity issues were also barriers to a smooth learning experience. Many had to travel back to their villages due to which they were occupied with different demands. Some students simply had preferences against digital modes. Despite these, students found innovative ways to join classes. For instance, some joined through phone calls instead of Zoom. Some, who lived close by, met and attended the sessions together using one device. In Sheikh Sarai, the participants also proactively did reflective homework. All this speaks to the fact that they find some value in coming to the sessions and are motivated to find their way to them every week.

Some participants were not fazed by the shift from offline to online sessions. However, many agreed that it wasn’t quite the same. Some asserted that the online medium made it easier to attend classes from home; others insisted that the offline sessions had a sense of socialising that virtual CSE didn’t. The class sizes decreased significantly, which also changed the experience of attending the sessions.

And understandably so — the online medium is an imperfect substitute for brick-and-mortar learning. The ‘whole’ of a classroom learning experience cannot be replicated by the sum of its parts.

Also read: Safe And Consensual Sexting During Lockdown: An Alternative For Sex?

Nonetheless, for two months in the lockdown, these online sessions were virtual safe spaces for learning, interaction, enjoyment, and growth in an increasingly uncertain and unnerving world. It encouraged me to think about the essentiality of these sessions for young people and the possibilities that social programmes usher.

Interestingly enough, as I monitored the sessions and spoke to the adolescents and facilitators about their journeys, I too negotiated and resisted the norms of my house in new ways — speaking a little loudly about reproductive rights, and queer experiences; making a little more room for my politics and voice at home.

Finally, without a massive resource investment, the sustainability and inclusivity of this medium raises concerns. Structural failures in addressing the worsening socio-economic inequities have made young people exponentially more vulnerable to financial, educational, familial, psycho-social, and political stressors. Amongst other things, safe spaces, community support and people’s movements are becoming increasingly important as we’re witnessing an assault on dissent and the needs of the most marginalised in our country.

Sharin (she/her) is currently pursuing her Masters in Psychology from the University of Delhi. Her research and work have centered around gender, mental health, sexuality and education. During the pandemic, she’s been thinking about conditions of worth that develop within family systems, personal and political negotiations at home, people’s relationship with hope and the spirit of protest movements. You can find her on Instagram.