At sixteen, when ‘divorce’ was still a word spoken by elders in grim whispers, during a summer break, Ammu’s story in Arundhuti Roy’s The God of Small Things had led me to painful and frightening moments of comprehension about the word. Thirteen years later, when my divorce story began to unfold, mere days after the wedding, I was still scared of the D-word. I would whisper the words ‘divorce’ or ‘divorcee’ to myself repeatedly, to somehow get past the strangeness of these words. As I gradually began to feel safe and unburdened, I wondered why I had sacrificed so much to save a marriage, which had left me with the last vestiges of self esteem.

I would whisper the words ‘divorce’ or ‘divorcee’ to myself repeatedly, to somehow get past the strangeness of these words. As I gradually began to feel safe and unburdened, I wondered why I had sacrificed so much to save a marriage, which had left me with the last vestiges of self esteem.

I found the answer, not in my story alone but together with the stories of numerous other women. Among them, there is a dear friend, acquaintances in professional spaces, strangers whose experiences were narrated by mutual friends and family.

Our stories unravel in similar patterns and within the last five-six years. Maitreyee, 30, after six years of marriage, realised that her husband had failed to keep any job for over a few months, was indifferent to her health and displeased with her housekeeping abilities and her professional success. Her financial resources were largely controlled by her husband who was unapologetic about his constant lies to her.

Also read: The Story Of Rani Salmani Who Survived Marital Violence To Become A Real Life Queen

Shobha, 26, after a no expenses-spared wedding, astonished by the indifference towards a new bride, realised that the husband, who was in a relationship outside marriage, had married only under parental pressure.

Shreya was 31 when her parents discovered that she was in an abusive marriage from the burn marks on her arms. By then, she had suffered the marriage for about two years.

Rajashree, in her early thirties, transformed herself according to the dictates of her conservative husband until his demands constituted a direct threat to her life.

The monetary and other demands of the in-laws and the husband continued to escalate for Sharanya, 28, until her life was considered at risk.

I have to restrict myself to a select few stories that represent so many more. The names of these individuals have been changed to protect their identities. I have, however, mentioned their actual ages to point to the fact that each of them were of age when it should be possible to make informed decisions about one’s own life.

While tales of violence and death are always closely associated with marriages in India, it is also difficult to ignore an unfamiliar equation between abuse and privilege that emerges from these stories. These women, born with normative body images in affluent upper-caste Hindu families, have escaped the discriminatory structures of the casteist, ableist society. They have ‘liberal-minded’ parents who encouraged them to seek prestigious degrees in business or academics from premier institutes of India and abroad. These women have continued to acquire professional successes in their respective fields. Only some of them are the ‘only child’ to their parents. In other instances, there are very supportive siblings involved. Some of them chose their life partners. Others, like me, entered into arranged matrimonial alliances with grooms who seemed to have similar profiles in terms of family, social and educational background.

From their loving homes, as they walked unsuspectingly into their terribly unloving marriages, their initial reaction was one of surprise. Soon, this surprise was replaced by self-deprecation and the desire to mold themselves to fit into their marital homes. Maitreyee recounts arranging and paying for expensive vacations for the husband. Rajashree’s mother silently puzzled over the loss of her daughter’s cheerful disposition, replaced with conservative dresses and behaviour as per the demands of the husband in contradiction to her non-traditional upbringing and lifestyle as an NRI. Shobha remembers the dark days of trying to play a happy newly-wed bride as per the customs, while increasingly growing aware of the husband’s infidelities. Shreya hid evidences of physical torture on her from her parents because she felt guilty, having chosen her own life partner who turned out to be abusive. Sharanya did not protest when she realised that the husband has been stealing her money to pay for his alcoholism.

Strangely enough, all these women believed that the onus was solely on them to ‘become better’ or ‘try harder’ to attain the love that they lacked in their marriages. In quite a few instances, these ‘socially-empowered’ women were also inclined to blame themselves for the conjugal inabilities of their respective spouses.

On a personal note, I am baffled now by my own almost self-destructive efforts to save the marriage. I began to feel a sense of grave disapproval, soon after the wedding, from the husband and his parents, about everything, from my wedding trousseau to my ability to do household chores. My contributions to household expenses were also considered dissatisfactory. I was quite aware of the increasing unfairness of their demands and yet persevered to live up to the expectations of that family. When my parents expressed concern over my severely failing health, I remember telling them that I was determined to make the ‘marriage’ work, as determined as I had been in my academic endeavours.

Eventually, my parents had a first-hand experience of my painfully unhappy existence in the ‘marital home’ and convinced me that I needed to extricate myself from the situation as soon as possible. In fact, in most of the afore-mentioned instances, a concerned parent or an older sibling or cousin was crucial to the decision of leaving a hurtful marriage. For most of us, divorce was a fearful thing, used as a threat to make us comply with the restrictions of our marital home. This realisation that the weapon of divorce, wielded against us had to be reclaimed, and be wielded by us against the perpetrators is the first moment of liberation.

However, procuring a divorce in India is not viewed ‘favorably’ by the existing judicial system, in the words of my divorce advocate. He usually asks his clients to give their marriages a chance but he made no such suggestions to me. He could see that as a family we had been traumatised and hoped to extricate me from this disastrous marriage as soon as possible. A mutual divorce, itself, would require me to observe a ‘cooling period’ for a year before the legal notice can be served. This was rather ironic considering the ‘waiting-period’ for a valid court-marriage in India is thirty days. These pro-marriage tendencies permeate all our systems. For instance, ‘being in separation from spouse’ is not a valid declaration of marital status and as an employee of a state or state-aided agency, salary components like HRA remain withheld or unsanctioned without spousal signature or till the court-declaration of the divorce. While spouses are encouraged to co-sign loans, little or no safeguard is in place to protect the interest of the individual, who having paid the loan, seeks to leave the marriage.

These systematic modes of propagating marriage is further strengthened by our cultural systems, where weddings are the only form of ‘happily-ever-afters’. My job often requires me to teach Nineteenth-century British novels to a group of twenty-year-olds. Brought up on a diet of Bollywood (and Hollywood) romances, they think Pride and Prejudice or Jane Eyre are love stories.

In a moment of rude shock, they realize that Elizabeth, after her marriage, will be under compulsion to bear a male heir for their beloved hero and lead an extremely decorous life in Pemberley at the cost of her free-spirited self or that Jane, for her happy ending, marries the hero who almost deceived her into a bigamous marriage. I look at their faces, a silent prayer for their future escaping me.

The distressing fact is that we grow up surrounded by a consumerist culture that nourishes and then feeds on a woman’s aspirations to be a ‘good’ married woman. The advertisement industry ensure that all our needs of good skin care, exquisite jewellery and all the wedding paraphernalia are aimed at our ‘Big day’ which is always the ‘wedding day’, not those rare occasions we are recognised for our professional success.

Our need for cutting-edge domestic appliances and nutritious food are tied up in our very essential abilities to be good caregivers in our marital homes. Our responsibilities as daughters, sisters or friends and our needs of self-care disappear from the dominant social narratives. Despite all our socio-economic capital acquired by birth and professional success, our emotional capital remain solely tied up in fulfilling the demands of being good wives, and by extension, good mothers and daughters-in-law.

Remarkably, women, with ‘divorce stories’, end up losing their emotional capital. To overcome the damages caused, they look for other means of self-preservation. In the process, they regain their emotional capital, this time in the form of self-love. From Aristotle to Ayn Rand, self love has been described as various forms of loving what is best about one’s self which becomes the foundation of developing relationships based on love, not only of the romantic kind. This decreases the possibility of gaining self-assurance by fulfilling the material demands of an individual, family or the society at large.

The women, whose trauma helped me survive my own and led me to write this, in remarkably similar terms, have expressed sincere joy at this second chance of life. Our divorces have made us stronger and kinder, wiser and happier than we have ever been in our lives. In the process of recovering from the personal crisis and its aftermath, we have grown accustomed to tending to our emotional and physical well-being.

Our divorces have made us stronger and kinder, wiser and happier than we have ever been in our lives. In the process of recovering from the personal crisis and its aftermath, we have grown accustomed to tending to our emotional and physical well-being.

Also read: Sumangali Prarthanai: Where Patriarchy Meets Tradition

Some of us have also become more aware of our socio-economic privileges, which unlike numerous other ‘daughters’ of India, enabled us to come home safe. Some of us had to learn forgiveness as an art and to gain expertise in the art with practice. Mundane pleasures like a hot cup of coffee with friends, family dinners or a quiet evening spent alone with a movie or a book, or finding time for a workout session or a hobby have become precious. Most of us have found our professional successes to be very satisfying. For some, it has been more difficult to get rid of the ‘dark’ memories. The rest have found the courage and the peace to begin new relationships. Now that we know how easy it is to lose all of it, we have began to take the responsibility of cherishing ourselves. Our divorce stories, quite like our wedding stories, have come to mark new beginnings.

Dr. Oindri Roy is an Assistant Professor in Gokhale Memorial Girls’ College, Kolkata. While her day-job is the chief driving force in her life, she finds solace and courage in the healing powers of the pen and the printed word. She has co-edited a book titled Approaching the Childhood: Issues and Concerns in Creative Representations. Her chief publications are in the field of post-feminism, critical race studies and the phenomenon of story-telling. You can reach her at oindriroy.20@gmail.com and find her on Facebook.

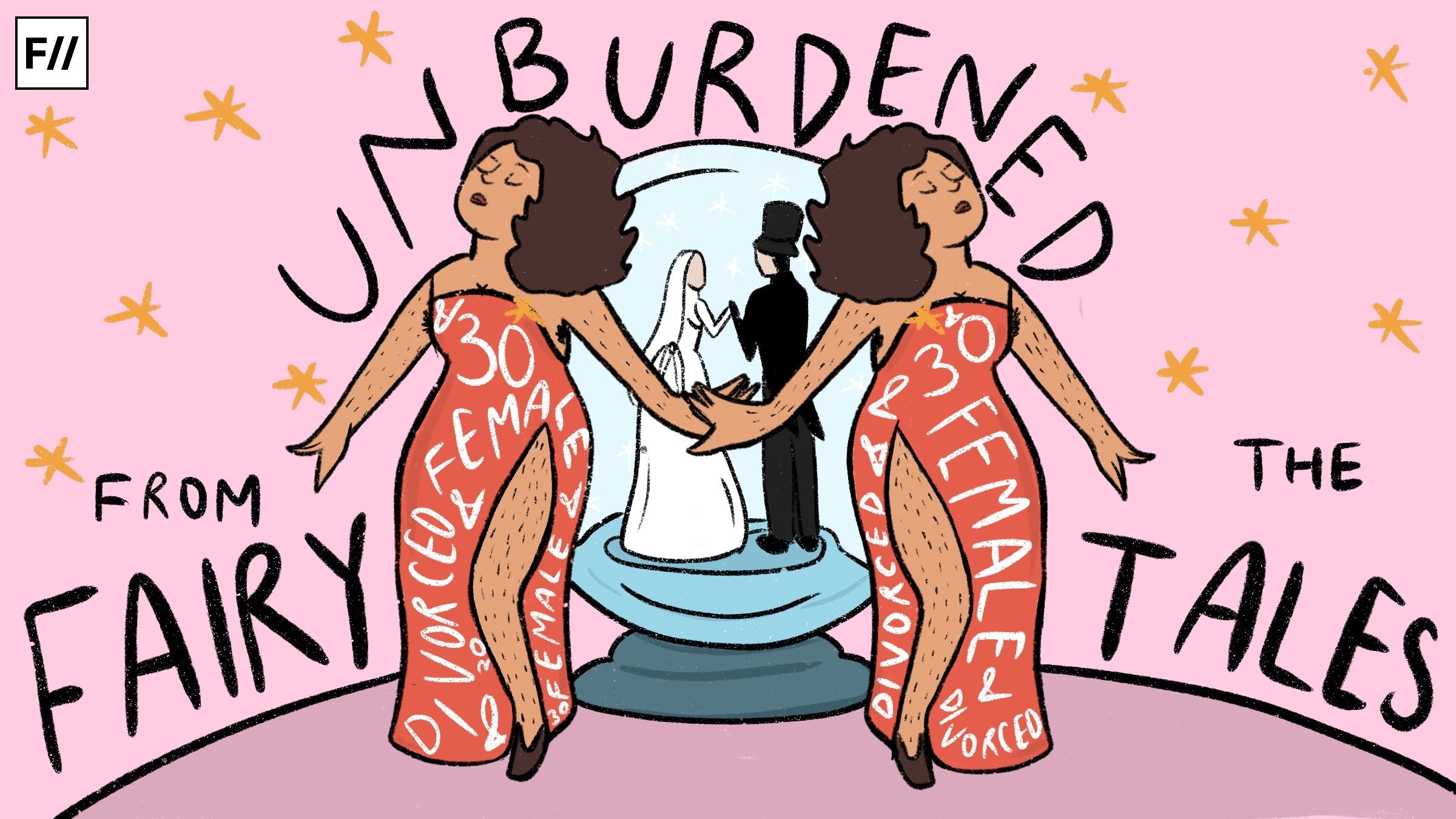

Featured Image Source: Shreya Tingal/Feminism In India

Sometimes it’s better for mutual divorce than killing the personal liberties of each other. Most of the educated couples take mutual decisions to be separate by filing mutual divorce by accepting the pros and cons of marriages.