Poetry communities in the past had been closed elite circles but spoken word broke that monopoly by putting poetry down the pedestal to where it belonged – to the people. It brought people together, gave a sense of community to so many and made poetry “cool” again.

It is comforting to see faces that looked like us, stories that talked about our lives and poems that felt like they were drawn out of our poetry closets. Simple people with their simple stories broke the Internet and opened the world to a new form of self-expression which is deemed to be somewhere in the middle of writing and performance arts. Spoken word became popular because it started as a movement to stand against oppression by amplifying voices of the ones who had been unheard or talked over for so long. The validation the poets receive from the audience made speaking up rewarding and left the marginalised with a sense of satisfaction of finally being seen.

However, although spoken word poetry started as a form of resistance and dissent, it is now turning into the very thing it stood against. Now that the spoken word industry is being commercialised heavily, more money being invested and more revenues opening up. It is being hijacked by the privileged, making the representation of any minority – be it class, caste, religion, gender, or sexuality, fade into thin air.

Daniel Sukumar, a spoken word poet who has performed A Guide To Personal Killings and When Farmers Can’t Be Terrorists, among others, says thus: “I have always felt uneasy to attend open mics in artsy cafes. I’ve never been to such spaces for the first 25 years of my life. These venues were meant for people from a certain socioeconomic background. This was apparent in the audience, their clothes, their English, their slang and their attitude. In more recent times, I am worried of being a poet in this digital space where everyone wants to be a brand. Success is measured by views, invitations to over-the-top poetry events or, TED talks. Rise of poetry organisations have made these spaces extremely exclusive. They have built themselves on the desperation of young poets by making money off their poems and never paying them. These spaces are filled with influential men who use their influence to sexually abuse women. I have no hope for these poetry groups and don’t want to work under their banner. I wish they focus on taking spoken word poetry to marginalised groups rather than brand building and star-studded events.”

Spoken word performance poets with performative wokeness and an audience performing hero-worship, certainly doesn’t sit well. Their loud revolutions can only be heard when there is the obvious presence of a camera. Poets who talk about “what’s trending” for social media clout might not be necessarily aware of complexities of the topic.

Spoken word performance poets with performative wokeness and an audience performing hero-worship, certainly doesn’t sit well. Their loud revolutions can only be heard when there is the obvious presence of a camera. Poets who talk about “what’s trending” for social media clout might not be necessarily aware of complexities of the topic. Political correctness in creative writing is not hard to get a hold of. The spoken word poet, oblivious to the nuanced realities of its politics, will grab some keywords and jumble them up to make poems out of it.

Men write rape apologies, open rape threats, or poems about rape by appropriating the voices of women and taking up space, letting their saviour complex go unchecked by saying things like, “I am sorry I couldn’t save you” or explaining our trauma or sexualising rape which is triggering and retraumatising for survivors. There are some poems that romanticise, trivialise, stigmatise, or misrepresent mental illness using suicide as a datapoint, invalidating experiences of survivors or dismissing it with toxic positivity. Online and offline audiences applaud and cheer for these poems out of sheer ignorance and the bigotry goes unchecked in the name of poetry.

John Berger’s infamous take on male gaze, that is ‘Women appear’, stands true for spoken word poetry spaces as well. Women in the spoken word poetry spaces are constantly judged by how they look rather than by how well they are at the art of spoken word poetry. They are still “female artists”, meanwhile the powerful, predatory men get to hide behind their craft. People comment on their looks and not their poems in offline and online spaces. Being a woman in Hindi or Urdu spoken word poetry spaces is extremely hard since these spaces are still run by sexist men who have made a career out of their misogyny and continue to exclude or ridicule women.

The prejudice that runs deep in our blood is troubling when it goes unchecked by the organisers that don’t take responsibility. There are some poems existing in online spoken word spaces that garnered a lot of views but in reality are regressive, problematic or even triggering like ‘Mai laat maarta hu feminism ko’ featured on Laughing Colours, ‘Mujhe naa bol kar mujhe balatkaari mat bana’ and ‘Mai hu nanhi pari Asifa’ to name a few.

Speaking of one of the biggest poetry channels in India, UnErase Poetry, which started on a high note with their progressive poems trying to fight stereotypes, also gave in to the fame-game shortly. Their poems like Maa mujhe marne de by Darshan Rajpurohit and The Legal Rapist by Simar Singh, the founder himself, are very well-cherished poems but extremely problematic. The former is an eyesore of a poem where a cis-het man writes about female infanticide and the latter where a man talks about marital rape, in the voice of the girl child and woman respectively. The poem by popular spoken word poet Yahya Bootwala, Jallianwala Bagh, talks about a historic incident from a perspective so oblivious of the suffering of people that it affected.

This is from one of the most influential poetry channels in India, and one can only wonder what is happening in not-so “woke” spoken word spaces.

“I was the first Indian poet to talk about dysmenorrhea through my articles and poems. When I saw Helly Shah’s poem on Spill Poetry that talks about it, I was upset to see so many ideas were taken from my work, which took me me years of experiencing, understanding, and writing. It was traumatic to have someone think I didn’t have the ‘right face’ for a paid project with their client, and go with another poet because of the way I look despite the fact that this was my life’s work. I have stopped going to the more famous open mic venues or any place where I don’t know the host will make sure we all feel safe. I started the group Non-male poets of Mumbai because I wanted to tell these organizers that shrug off any responsibility of representation by saying they don’t know any women/queer/trans/dalit/muslim/disabled/neurodiverse/other minority artists. Male poets are paid more or are given paid opportunities on a platter within their closed circles. These inner circles include male poets and few women poets that are their friends and fall under the traditional standards of beauty that brands apparently look for” says Ishmeet Nagpal, whose spoken word poetry on Revenge Porn and titled Dear Non Depressed Friend are popular, among others.

Appropriating the stories and lived experiences of people from the margins by sprinkling ill-researched buzzwords and making money out of their misery has been a tried and tested trope in the spoken word poetry business now. Capitalising on their suffering and stripping them off the one thing that they had, their voice. Revolutionary poetry is a trend. Performative woke poets hijack the movements by becoming the face of it and hog unnecessary space while getting credit for doing the bare minimum. This increases the gap of representation that is already extremely low in most spaces including spoken word.

Also read: Five Hard-Hitting Spoken Word Poems About Being A Woman In India

Parth Rahateka, another spoken word poet, says, “I think poets, especially the younger ones are looking out for each other and there are people like Nandini, Shantanu, KC Vlaine and so many more who are willing to put in the work to educate and create responsible voices. I think some onus rests on us to constantly look for representation from the margins and amplify those voices.

Aspiring spoken word poets must take note that it is important that they do not forge poetry to be viral or write on something just because it is trending. It is important that one does not take up space under the disguise of “empathy”. If a spoken word poet wants to speak or write about an issue that doesn’t directly affect them, then they should not write in first person POV.

Aspiring spoken word poets must take note that it is important that they do not forge poetry to be viral or write on something just because it is trending. It is important that one does not take up space under the disguise of “empathy”. If a spoken word poet wants to speak or write about an issue that doesn’t directly affect them, then they should not write in first person POV. If you want to write a revolutionary poem, do it by looking within your community and reflecting on your own standpoint.

Remember that someone’s trauma is not your aesthetic.

Poetry is political and it cannot be separated from the realities of the socio-economic, religious or gender politics. It is a weapon of dissent as much as it’s for romance and beauty. Together, we can make what spoken word poetry really is, a radical call for social change and make our spaces safer, more accessible, and inclusive.

Our country has belonged to cis-het upper caste men, the spaces of spoken word poetry that we nurtured do not have to.

Ghazal Khanna is a confessional poet, writer, and educator. She started writing at the tender age of 10 and first got published at the age of 12 in a local magazine. Her work has been featured by platforms like She The People, Zoom, Times Now, Haldiram Nagpur, Buddybits, Poems India, Kommune amongst others. Her poems have been nominated for Orange Flower Award – Poetry by Women’s Web. She extensively talks about her lived experiences as a queer brown woman through prose and poetry. She can be found on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and here.

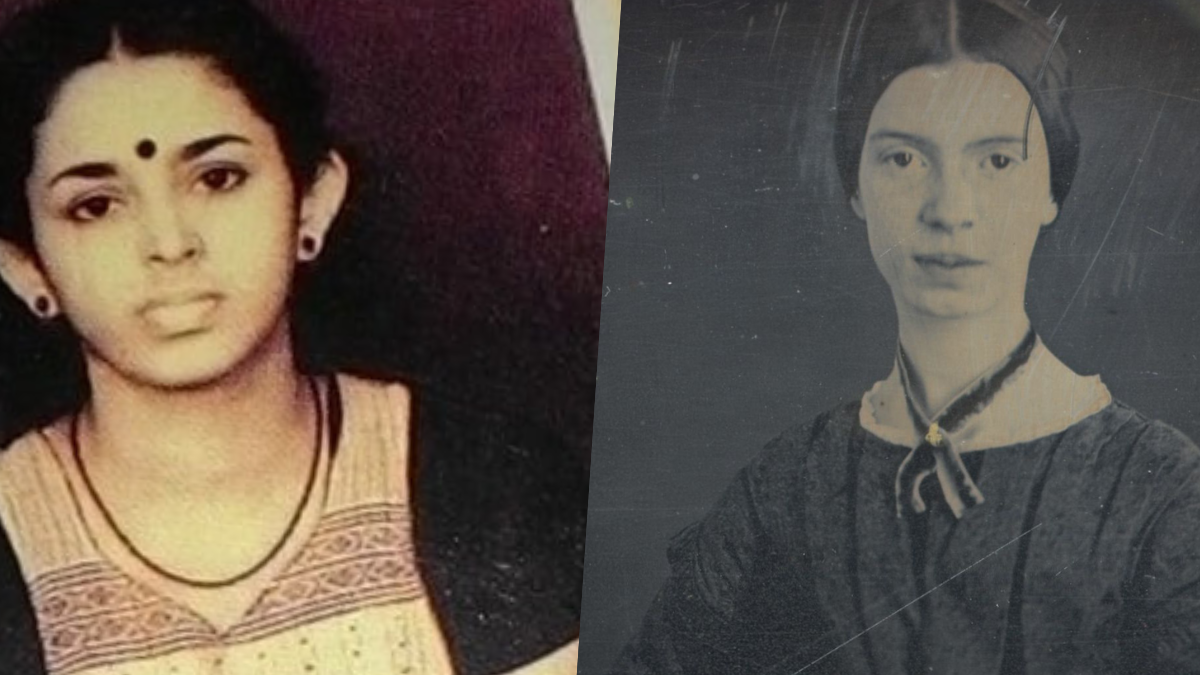

Featured Image Source: Scroll.in

Absolutely brilliant article

This article touched me from the perspective of an American who cannot imagine our spoken word spaces dominated by the same ole heteropatriarchy. Our men comfortable performing this type of poetry are few. This is the way of all art: spaces that allow men soon become spaces FOR men. Unfortunately the only solution I can think of is what has worked here, somewhat. Spaces wishing to focus on somebody other than straight men need to explicitly let that be known, along with the notion that these nights and spaces exist as places where it’s encouraged for straight dudes and their flunkies to let some of their thoughts go unexpressed. Which is a rarity worldwide.