Posted by Ishani Dutta

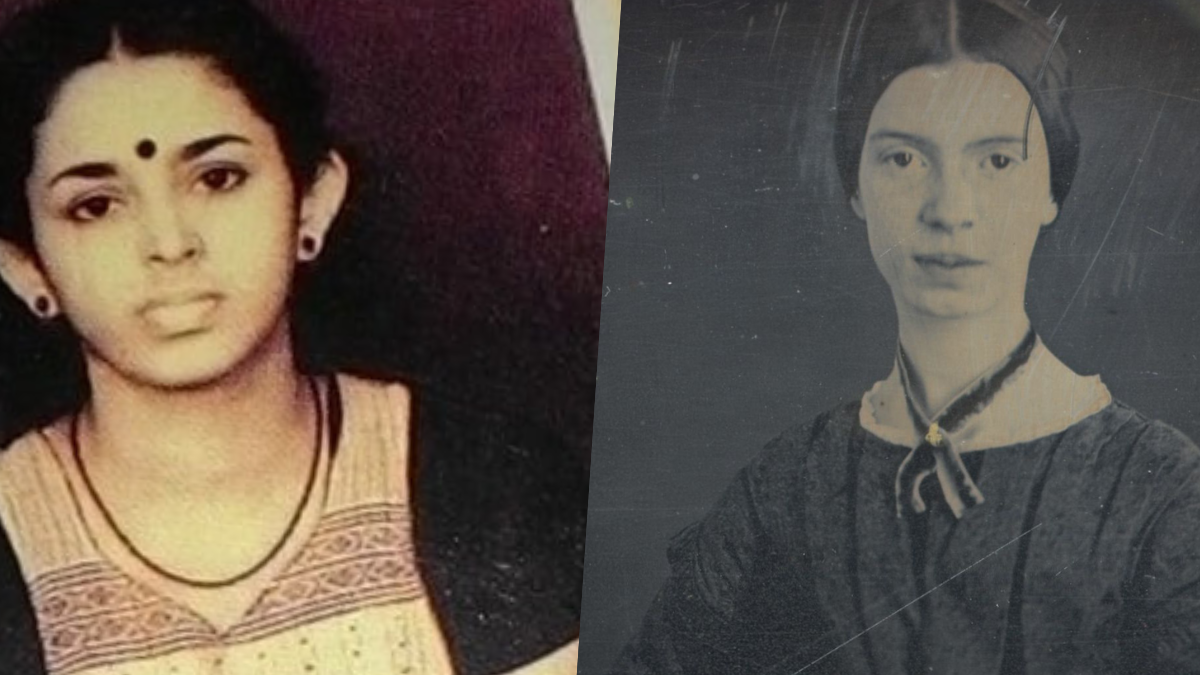

A public administrator by day and Indian-Nepali poet by night, Pavitra Lama is attempting to write a new chapter in India’s rich tradition of performative arts with avisangi kavita. Overcoming the challenges posed by being in a rather remote corner of the country, Pavitra Lama has been steadily—and quite successfully—charting a new path in Indian-Nepali literature, taking it from the confines of the pages on to the stage.

तपाईँ जतिसुकै निम्छरो भविष्य दिनुहोस् हामीलाई

हामी पिलाउनेछौं तपाईँलाई विशुद्ध चिया ।…

दुई शताब्दीपछि पनि हामी कमानेका कानहरू

कतिसम्म औपनिवेशिक हो कुन्नि

हामीले साइरन र जिन्दगी एउटै बुझ्यौं…

No matter how silenced a future you give us

We will serve you pristine tea…

Even after two centuries

How colonised can our ears be?

We believed siren and life are the same…

(Translation by author)

Strains of a soft, evocative music fills the space, setting the tone for Pavitra Lama’s performance. Usually clad in a sari, a shawl draped on her right (its colour playing a symbolic role), she begins reciting her poetry. The collective universal experiences and the overlapping voices of women and the marginalised people from different backgrounds have found voice and expression in Pavitra Lama’s rendering as an avisangi. In a 7 to 10 minute performance—combining ‘abhi’naya (acting) and ‘sangee’t (music)—Pavitra Lama, also the West Bengal deputy collector, captures the audiences’ attention with her voice modulations and effective gestures, drawing out laughter, anger and despair; but, most importantly, leaving her thoughts with them long after her performance has ended.

“My poems tend to link the issues in one part of the country to those in another…At the core, the struggle is always between the centre and the periphery, and the marginalised and the mainstream,” says Pavitra Lama.

Also read: The Search For Caste Solidarity: Dalit Women In India And Nepal

Reinvent to Revive

The Indian-Nepali community, also known as the Gorkhas, primarily resides in and around the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal. The community is still struggling to come out of an identity that has been forced upon them: that of being soldiers or tea-garden workers. On the language front, Nepali was recognised as one of the 22 languages by the Eighth Schedule to the Indian Constitution in 1992, but it had been an official language of the state of West Bengal since 1961. In a bid to strengthen their identity, Indian-Nepalis are trying to redefine their cultural and literary productions in such a way that they would define the community. One such endeavour—that of avisangi kavita—is being spearheaded by Pavitra Lama.

Born in Dooars in 1976, Pavitra Lama has been writing poetry since she was four. Over the years, “I, along with many of my contemporaries, had come to realise that people both within and outside the Indian Nepali community had been losing their connection with poetry. Additionally, they did not have the same relationship with printed literature as they once had,” she explains. In 2015, Pavitra Lama gave her first performance at a dhamari (a competition akin to slam poetry competitions) conducted by the Nepali Sahitya Sansthan in Siliguri.

She won!

Emboldened, since then Pavitra Lama has not only been performing across the state but also published two poetry books, Sabhyataka Pendulamharu (2016) and Ma Deh Raato Ranginchu (2019). A handful of others have also started taking up the style and begun ‘performing’ their poems in a bid to garner more interest. Avisangi realises the fact that the future of Indian-Nepali poetry is with acting and music, says Pavitra Lama, the daughter of a musician.

What constitutes an Avisangi performance?

One can’t deny the similarities between avisangi and the Western style of slam poetry, an element that traditionalists have held against this new genre. However, Pavitra Lama maintains that avisangi kavita is far from being just performance poetry. It is envisaged as a complete theatrical performance, akin to a mono-act, with either live or pre-recorded music.

The narrator pf avisangi kavita takes on multiple characters and roles, depending on the content, a distinction Pavitra Lama often makes by changing the colour of her shawl to set apart one poem from another. Black (for protest) and red (representing the domestic ties of women) are her preferred colours.

The narrator takes on multiple characters and roles, depending on the content, a distinction Pavitra Lama often makes by changing the colour of her shawl to set apart one poem from another. Black (for protest) and red (representing the domestic ties of women) are her preferred colours.

The term avisangi kavita was coined in 2015–16 by the Indian-Nepali critic and poet Jai ‘Cactus’ Gurung after closely watching and analysing the features of her performances, which he realised were different from slam poetry or Western performance poetry. Currently, Gurung and Kabir Basnet (Pavitra Lama’s husband and a professor of Nepali literature) are helping her in the theorisation of the genre through the canonical text of the Natyashastra, while taking into consideration the reaction of the audience during and after the performances.

An avisangi often begins with one instrument, the other musicians chime in between stanzas or poems during the course of the performance. Each musician gets his/her own time to play their instrument––mostly flute, violin, guitar and synthesiser. The music is composed according to the poem, and plays an equally important role while communicating the poem’s essence to the audience. In fact, Pavitra Lama often sings portions from poems instead of just reciting them for added effect. Keeping a helping parchment with the poem is an absolute no. It has to be memorised for full impact. During the seven to ten-minute performance, the communication between the poet and the audience is sacrosanct.

Also read: Axone: The Problematic Representation Of The Nepali Community In The Film

Challenges in Pushing Boundaries

Along with form, Pavitra Lama is also stretching the boundaries of content by including voices of refugees, women and transgender persons, along with the extant social issues and nature. The key feature of the genre is its desire to reach out to every section of the society, irrespective of age, class, caste, gender, religion, etc. The primary motivator behind avisangi kavita is the belief that poetry mixed with performance will not only be successful in bringing poetry back into the mainstream but in the process, will also draw people’s attention towards issues that are often overlooked both within and outside the Indian-Nepali community.

The language used is simple so that it is widely understood, but universal in intent. Most of Pavitra Lama’s poems centre around patriarchy and the marginalised. Lama’s attempts, though, are not without challenges and criticisms.

Traditionalists believe the performance aspect of Pavitra Lama’s poetry overshadows the literary aspect of the poem. In addition, the volatile socio-political scenario in the Darjeeling hills often hampers literary innovations. Furthermore, genres like avisangi kavita are very region and language-specific, and even though they are universal in their approach, they cannot help but be limited in their reach, until a new generation of poets, performers and researchers decide to take the legacy forward—which is exactly what Pavitra Lama is hoping for.

This Saha Sutra article is part of the module on ‘Performing Avisangi: Indian Nepali Performance Poetry in the Darjeeling Hills’ on www.sahapedia.org, an open online resource for the Indian arts, culture and heritage.

Ishani Dutta is currently pursuing a PhD from the Centre for Comparative Literature, Bhasha Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University, Bolpur, West Bengal. Her areas of interest are literature and other arts, and translation-in-practice.

All pictures as provided by Sahapedia.org.

About the author(s)

Sahapedia.org is an open online resource on the arts, cultures and heritage of India.