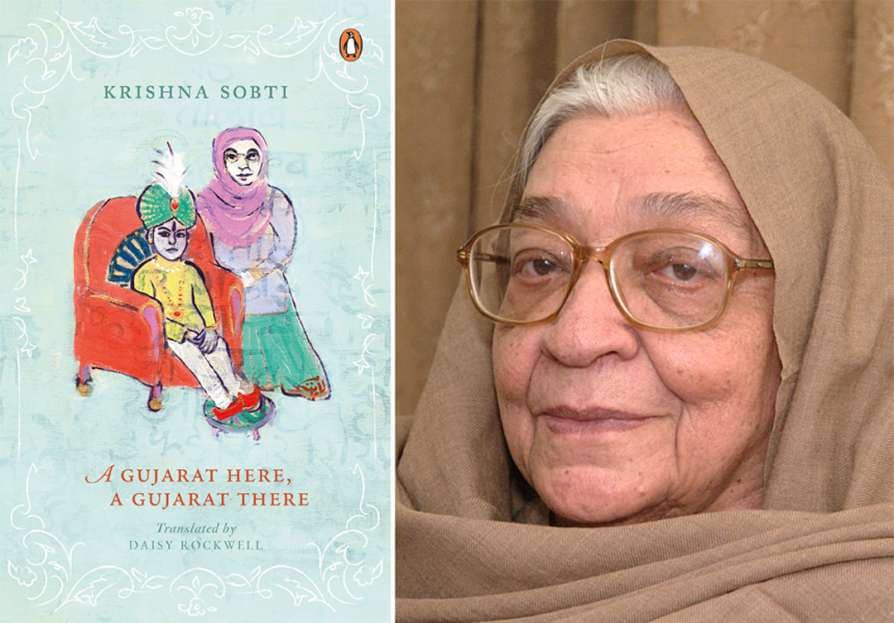

Reading Krishna Sobti’s ‘A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There’ is like a garland of mixed flowers, a pricey necklace that you like to admire but not wear. In Daisy Rockwell’s apt and timely translation of Krishna Sobti’s work the texture and flavour of Sobti’s writing is reinvigorated. She imbues the original work with a warm, tender insight into the lives of the ruling class, and peeks into the lives of the women and children in the royal family. She is like an aunt, in all our families who doesn’t mince any of her words.

A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There

Author: Krishna Sobti

Translator: Daisy Rockwell

Publisher: Penguin Random House India

Genre: Historical Fiction

What is best about her book, is that her writing reflects the fluidity of the time, a passage here interweaving memories from a past, of a life in Gujarat, Pakistan to a passage here describing her efforts and encounters as she starts a new life in Sirohi in Gujarat, India.

What is best about her book, is that her writing reflects the fluidity of the time, a passage here interweaving memories from a past, of a life in Gujarat, Pakistan to a passage here describing her efforts and encounters as she starts a new life in Sirohi in Gujarat, India. As a refugee, she encounters and scoffs at several situations and people in this princely state. For instance, when she is asked to declare her refugee status in a government form to have access to free blankets and food.

You are shaken by the jump cut style of her writing because she isn’t trying to molly coddle you. The transitions in her writing are symbolic of the jump starts of her life after leaving home, moving to a refugee camp and later getting a job as a governess in the royal family in Gujarat. These transitions mirror her own mixed feelings, joys and novelty of this new life and sadness of never being able to relive the life she left behind in Pakistan.

She often reins in her mind, saying, “Go over there, dreams, scram! What’s the point of peeking over there, now that you’ve changed your disguise to fit in here? I no longer owe anyone anything“

Also read: Book Review: The Last Queen By Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Her writing shows her constant yearning for the past, and desire to create a new life are at constant loggerheads, when she writes, “Ancient teachings for ancient times. Do our pathways change when we ourselves change? I could never have imagined that one day I would look with my own eyes on this landscape of bygone days. The country is moving forward after -Independence – and these princely states are trying their hardest to carry on with the old ways. Ancient schemes. Ancient customs.“

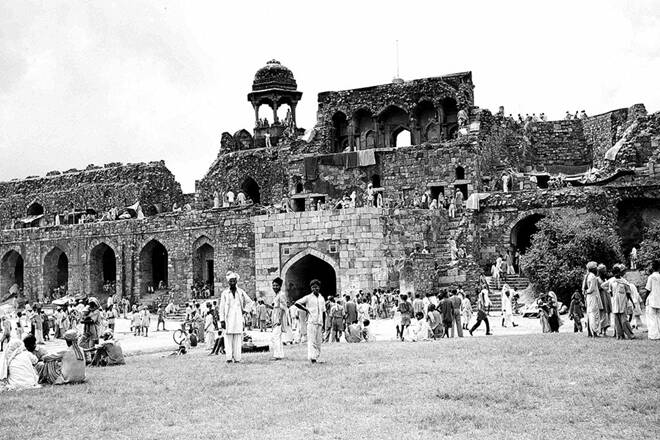

She writes about long train journeys, and the turmoils in Gujarat-Rajasthan over the statehood of Abu in Sirohi. This township hosts the Amba temple, deeply revered by Gujarati community, which ended up being part of Rajasthan.

“When you uproot a tribe, it scatters with the destructive power of an earthquake. Everything goes topsy-turvy. Up is down, and down is up,” she writes.

She contrasts her journeys in erstwhile Pakistan and now in India: while travelling by Frontier Mail one could walk into the pantry to get tea, while the train in Gujarat had a vendor who would come at his convenience to serve tea. This is how she admonished her own mind for being too reminiscent of her past.

Krishna Sobti’s memoir is still relevant to our times. How we have set up borders that divide us instead of unifying, in a more polarised world, how we are lost in ambiguity, and silences of the ones who have no voice, or are responsible equally for the silences we encounter.

Sobti also unabashedly but righteously logs incidences of injustices and women reproducing patriarchal values in her descriptions of the royal family. How the Maharaja’s first wife who couldn’t conceive a royal heir finds another wife for her husband to bear them a child and ends up adopting him to be successor. Sobti is hired to be the interim governess of this child, who is already wise and intelligent as an adult, maybe too intelligent in Sobti’s own words.

In their first encounter he forewarns her that the reason he has been throwing up on the driver every morning since she had started was of her own volition, and she will be reprimanded the next day. Although he is advised by the Queen not to reveal this, he kindly states to her that he has been eating his medicines after having breakfast which is upsetting his stomach. A minor detail Sobti in her amateur way had overlooked but the Prince in his wisdom brings up to prevent any annoying follow ups. Clearly, he has taken a liking to her.

Also read: Book Review: Dewaji—Making Of An Ambedkarite Family By Dipankar Kamble

We don’t find any other instances where he is shown to have any emotions or feelings. He is treated like a toy prince who has to learn the tricks, ways and customs of the royalty. Sobti doesn’t easily give into these ancient customs, which is why, we are told she knows this is not a permanent job for her, and she will move on eventually.

A similar personal incident, where in a letter from her father there is an incident of Sushma, fondly called Sushi. Sushi comes first in an essay competition with Hindustan Times-New York Herald Tribune, where the winner gets the chance to go to a foreign country. But because she is a girl, this opportunity goes to a boy. Sobti has a keen eye to such injustices around her and minces no words to put them across to her readers.

Even having left her home, in the twilight of Partition, she observes a world where the powerful still continue to retain their titles, squabble to keep their power, and establish their superiority by drawing people along caste lines. Sobti has a darling encounter with the young prince who must not have been more than five years old, when Sobti must have been the governess. Tej Singh asks her what caste she belongs to, he may still not know how it divides, but wants to know whether she is a Baniya, or Brahmin. Initially she desists giving a response, but then ends up narrating her family lineage, the satraps who followed Alexander, and families who responded to the call of arms by Guru Gobind Singh.

Krishna Sobti’s memoir is still relevant to our times. Mentioning how we have set up borders that divide us instead of unifying, in a more polarised world, how we are lost in ambiguity, and silences of the ones who have no voice, or are responsible equally for the silences we encounter, Sobti writes, “She closed her attached case, checked her luggage and began looking out of the window. The vastness of the Indian terrain! How large our country is. Rajasthan’s borders reach out to Gujarat. Sometimes settlements and people must also be pushed across borders.“

As a reader, you take this journey with Sobti and know that she, like us, has transformed.

Also read: Book Review: Why I Am Not A Hindu Woman By Wandana Sonalkar

Featured Image Source: Cover page of ‘A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There’ (L), Krishna Sobti (file pic: Wikipedia)