Trigger Warning: Rape

When discussing sexual violence against women and India’s pervasive rape culture, people often point out India’s incredibly low number of reported rapes, taking this to mean that sexual violence against women isn’t as bad in India as it is in most, often more developed, countries across the globe. India’s lower number of reported rapes aren’t a result of lower instances of violence but resultant of socio-legal barriers that keep millions from reporting sexual violence. Social ostracisation, stigma, familial pressure, law enforcement apathy, tedious judicial proceedings, and the economic and emotional strain of pursuing judicial remedies, all keep victims of sexual violence from reporting crimes. Add to this the fact that most rapes are committed by someone known or related to the victim and this number of unreported rapes could be unfathomably high. And in this discourse, the remarks by SA Bobde, the honourable CJI, is quite relevant, and calls to be problematised.

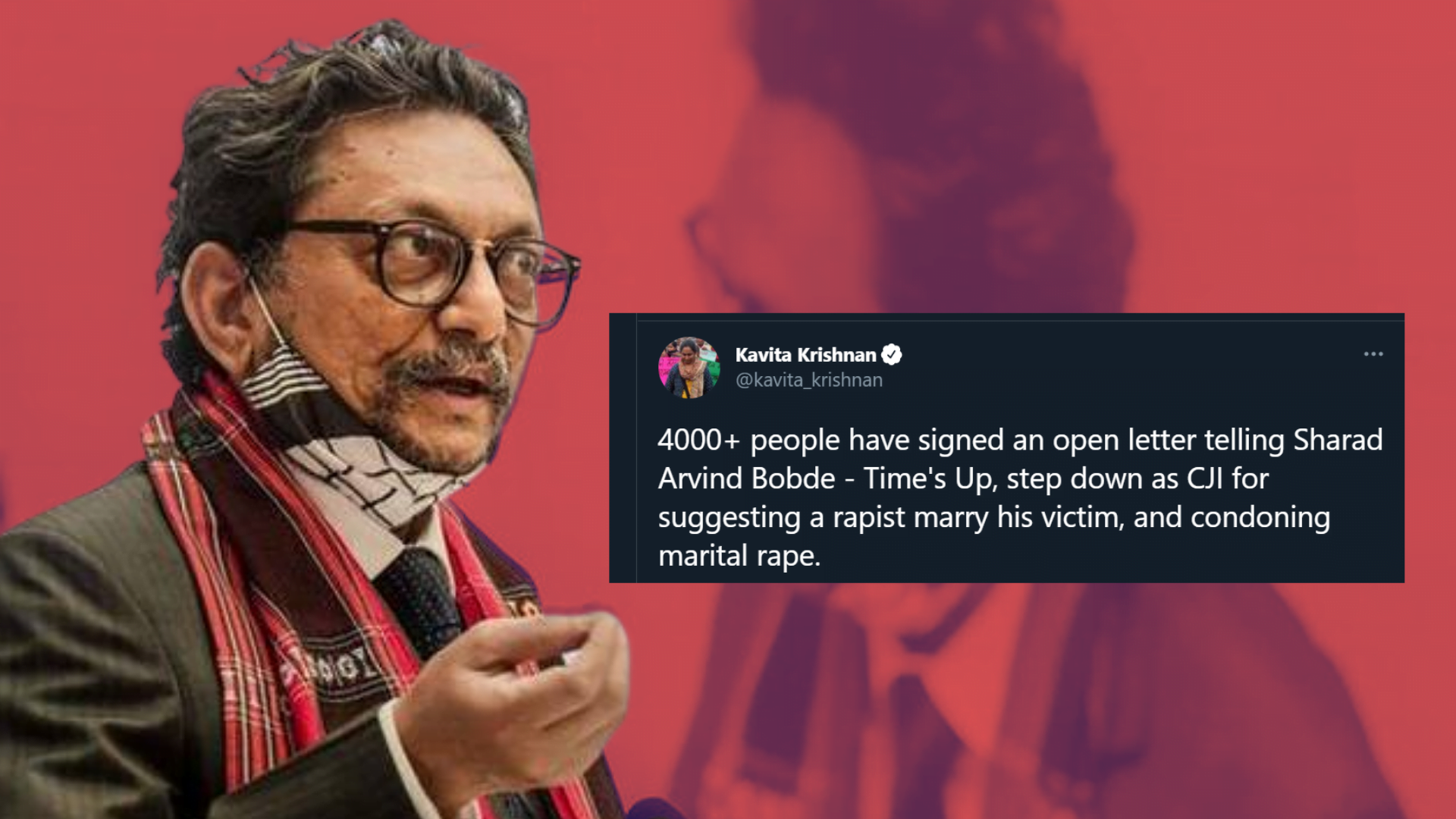

Adding to this culture of impunity these perpetrators enjoy, a Supreme Court bench led by the Chief Justice of India asked an accused rapist if he would marry the victim, whom he raped repeatedly when she was a minor.

Even when sexual violence is reported, securing a conviction is still hard. According to the NCRB, the conviction rate, as of 2020, is an abysmal 27.2 per cent, which means only 28 of every 100 accused rapists actually face prison time. Speaking to The Economic Times, Vani Subramanian of Saheli said, “The low conviction rate shows that perpetrators of sexual violence enjoy a high degree of impunity, including being freed of charges.” Adding to this culture of impunity these perpetrators enjoy, a Supreme Court bench led by the Chief Justice of India asked an accused rapist if he would marry the victim, whom he raped repeatedly when she was a minor.

Also read: Priya Ramani’s Victory Is A Hope For Many Who Said #MeToo

The CJI, while hearing a petition against an order by the Bombay High Court rejecting a sessions court appeal granting the accused anticipatory bail, said, “If you want to marry [her] we can help you. If not, you lose your job and go to jail. You seduced the girl, raped her.” He further added, “We are not forcing you to marry. Let us know if you will. Otherwise, you will say we are forcing you to marry her.”

The crime took place sometime around 2014 when the victim was still a child in school. The accused, who is a relative of the family, assaulted the young girl on more than one occasion. When she and her mother went to file an FIR, they were approached by the accused’s mother, who said her son would marry the girl if her mother would sign a written declaration claiming the sex between them was consensual. Even if this were true, this would still be illegal given that the age of consent in India is eighteen and any sex engaged in with a minor would be statutory rape; noting this, the Bombay HC denied the accused from seeking anticipatory bail. While the Supreme Court didn’t reverse this decision, it allowed the accused interim protection from arrest for four weeks to seek bail from a sessions court.

This isn’t the first instance where the CJI making such outrageous remarks in court, either. A few days ago, the CJI had said, “When two people are living as husband and wife, however brutal the husband is, can you call sexual intercourse between them rape?”

This isn’t the first instance where the CJI making such outrageous remarks in court, either. A few days ago, the CJI had said, “When two people are living as husband and wife, however brutal the husband is, can you call sexual intercourse between them rape?” He made this remark while hearing a case where a woman accused her partner of sexually assaulting her. The CJI further added, “Then you file a case for assault and marital cruelty. Why file a rape case?” The CJI-led bench, in this case too, granted the accused interim protection from arrest.

Also read: The Supreme Court’s Restricted Legal Understanding Of Rape & Marriage

Over 4000 activists, social justice groups, and citizens have now written an open letter to the CJI, demanding his immediate resignation. A section of the open letter read: “We bore witness when your predecessor sat in judgement over an accusation of sexual harassment against himself, and lobbed false, defamatory attacks on the complainant and her family from the Bench of the Supreme Court. An appeal against the atrocious acquittal of a convicted rapist on the premise that a woman’s Feeble No might mean a Yes’ was not admitted. You have asked why women farmers are being ‘kept’ in protests against farm laws and asked for them to be ‘sent back home’– again, implying that women lack the autonomy and personhood that men do. Then yesterday, you said, ‘If a couple is living together as man and wife, the husband may be a brutal man, but can you call the act of sexual intercourse between a lawfully wedded man and wife as rape.’”

This isn’t the first time the Supreme Court has been subjected to criticism for its callous handling of matters related to violence against women. In 2019, CJI Bobde’s predecessor, Ranjan Gogoi, was accused of sexual assault by a junior assistant. Following which, in a widely-criticised move that disregarded key tenants of natural justice, Gogoi himself lead a bench that heard the facts of the case.

By offering marriage as a remedy to rape, the CJI not only approaches the issue of sexual violence against women with callous disregard and insensitivity, but also undermines the position of the Supreme Court and highlights the institutionalised bias against women that makes a justice system that claims to be for everyone, openly hostile to women.

This is another reason why women hesitate to come forward. During the height of #MeToo, when several allegations were levied by men in positions of power, their accusers were often dismissed and their claims rubbished for their protracted silence. In fact, whenever women come forward to out their abusers, they are asked, if the allegations are true, why they would wait so long to go public; why they didn’t approach the police; why they didn’t pursue criminal trials: shifting the onus of proving innocence on to the complainant and not the accused. This is why. Sexism and patriarchy are institutionalised in this country; when law enforcement agencies and courts are hostile towards women; when they parrot dated, patriarchal ideas about sexual violence; when the CJI of the country thinks that marital rape is not rape and instead, thinks asking rapists to marry their victims is justice; then what should the women of this country resort to?

When the CJI of the country thinks that marital rape is not rape and instead, thinks asking rapists to marry their victims is justice; then what should the women of this country resort to?

When courts and law enforcement agencies harbour rape apologists’ intent on protecting abusers, why won’t women continue to stay silent? And the women who don’t stay quiet are advised to marry their rapist and told their consent has no value in a consensual relationship, they are tried for criminal defamation for speaking their truth, they are bullied and receive threats, they are called liars looking for their fifteen minutes of fame. Whether women stay quiet about sexual violence or not, whether they report violence immediately or not, there is no winning. Perpetrators enjoy impunity; institutionalised, systemic impunity.

Not long ago, in criticising the Centre’s handling of the farmer protests and refusing to issue an order to stop the protests, the CJI had asked, “Why are women and elders kept in the protest?” He also asked advocate H S Phoolka to ‘persuade’ women and elderly protestors to go home. The use of the word ‘kept’ speaks volumes about the CJI’s dated and regressive ideas about women and the willful refusal to see and acknowledge women’s autonomy.

Women, fully aware of the institutionalised biases against them, have long had little to no faith in the institutions of this country. But if the Supreme Court, the most powerful judicial institution of the country, becomes complicit in furthering this culture of violence and impunity, then this really is no country for women. The callousness and lack of nuanced understanding displayed by the CJI speaks to how our biases, sexism, and lack of acknowledgement of women’s autonomy are being increasingly institutionalised every day. We fail women in this country every day. Our governments, law enforcement agencies, our courts, and our citizenry, all of them fail women and we don’t seem to want to do better. The CJI making these remarks shouldn’t be just another story on the news cycle that will die down when something more ludicrous or outrageous happens, it should instead remind us of how men at the helm of powerful institutions continue to foster a culture of impunity at the cost of doing right by women.

The Supreme Court’s emblem reads: यतो धर्मस्ततो जयः॥ – Where there is righteousness, there is victory; but with the politics of privilege, gender, sexuality, religion, caste, and class in play, our justice system often has little justice to offer.

Featured image source: Feminism In India

About the author(s)