In November 2011, J. Jayalalitha, the then Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, presided over a state-sponsored ceremony celebrating the birth centenary of actress and filmmaker TP Rajalakshmi. The Chief Minister, once the leading lady of Tamil cinema herself, had chosen to pay tribute to a little-known celluloid antecedent of her own. In doing so, she had breathed life back into the glimmering legacy that many of her once-peers and current successors in the film industry had all but forgotten. Here was one screen legend revitalising the afterlife of another. Understated as it may have been, it was a decisive moment for Indian cinema.

Enough evidence exists to suggest that Fatma Begum laid first-claim to this distinction with her 1926 production Bulbul-E-Paristan; Rajalakshmi, nonetheless, would become the second Indian female director exactly a decade later, and the first from south India.

Nevertheless, the late Chief Minister’s initiative remains the last, most recent, formal effort to honour TP Rajalakshmi’s contributions to the art form. Today, her career remains reduced to a handful of factoids that are exchanged sporadically among Indian cinephiles and the occasional mention in the odd film history book for those who are motivated enough to buy one. A rare and curious newcomer to TP Rajalakshmi’s life is always initiated through the same two remarkable trivia lines: she was the first actress of Tamil and Telugu cinema, and that she was also the first woman director in Indian film history. The latter achievement, however, is disputed.

Enough evidence exists to suggest that Fatma Begum laid first-claim to this distinction with her 1926 production Bulbul-E-Paristan; TP Rajalakshmi, nonetheless, would become the second Indian female director exactly a decade later, and the first from south India. Her life, though, was far too exceptional to be hastily pared down to just a couple of (admittedly mighty) accomplishments. A true Renaissance woman, TP Rajalakshmi overcame inordinate odds to attain a summit that few before her, women or men, had dared to scale.

Also read: Tamil Cinema And Its Misogyny Endorsing The Vain Macho-Hero Image

Early Life

Born on 11th November 1911 (this fortuitous date might seem somehow significant to the more superstitious reader), Thiruvaiyaru Panchapakesa Rajalakshmi was the daughter of an accountant from the village of Saliamangalam in Thiruvaiyaru in what was then British India. Foreshadowing a life in the performing arts, she had the uncanny ability even as a young girl to reproduce a song effortlessly as soon as she had heard it. Hence, music was the first form of creative expression that TP Rajalakshmi discovered independently. She would remain, thus, among other things, a singer for the rest of her life.

However, these talents were neglected by her conservative Brahmin family, who proffered her hand in marriage to a much older man when she was just seven years old; she was accepted. Propitiously, though, the couple never got along, and Rajalakshmi returned to live with her parents shortly after the wedding. In addition to this, the dowry demanded by the family she had been pledged to was never paid in full by her father, who soon died by suicide, leaving the girl and her mother to fend for themselves. Seeking better opportunities, the mother-daughter pair relocated to Trichy, where Rajalakshmi discovered a second art form, theatre.

Her stage debut was facilitated by the intervention of Sankaradas Swamigal, a pioneer of modern Tamil theatre, who recognised her talent and ensured her induction into a well-reputed drama company in the city. Performing at a time in history when men played women’s roles with overly feminine affectations, T.P. Rajalakshmi became one of the first-known female actors of the early-modern Tamil stage. This would be the first of many glass ceilings she would rise above.

Also read: The History of Anti-Hindi Agitations In Tamil Nadu And Why We Must Fight Hindi Imposition

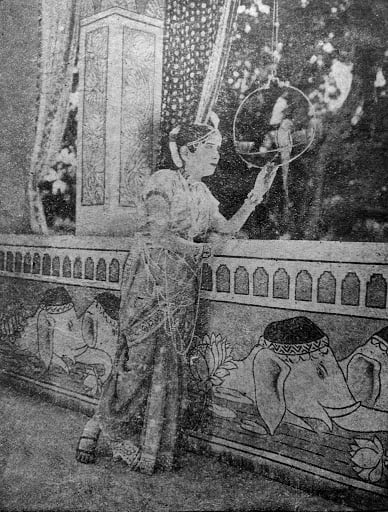

Her newfound celebrity was met with disdain from her estranged “husband”, who soon dissolved their union. Free at last from any and all connubial obligations, Rajalakshmi’s thespian stardom flourished from strength to strength. She appeared in productions that were staged not just in the subcontinent but also in other far-flung possessions of the Empire, including Singapore. Beginning as a contract player, TP Rajalakshmi’s stature as an actress ascended rapidly enough for her to become a “special drama” star by the time she was just eighteen. This meant that she could perform, in effect, as a freelance artist, unbound by stipulation to any one theatre company. This was an honour usually reserved for essential doyens of the business; she became the first doyenne.

In 1925, Rajalakshmi had moved to Madras (now Chennai), where the first rumblings of a rising entertainment industry were growing louder. Inevitably, she would soon be drawn into its orbit.

Cinema

Like repertory companies, early Indian film studios relied on an in-house troupe of performers to repeatedly appear in their productions. These seasoned artists were almost always drawn from the then-dominant theatre scene. Rajalakshmi was, thus, contracted by General Pictures Corporation, one of the earliest film production studios in the South, because she was a (teenage) veteran of the stage. She made her screen debut with the silent film Kovalan in 1929, making her the first film actress of Tamil cinema. She then moved to the Associated Film Company, where she appeared in a further couple of productions. TP Rajalakshmi became acquainted with K. Subramaniyam, an influential director of the early days of Tamil and Telugu cinema.

Also read: Tamil Refugee Women In India: The Unsung & Stateless Who Saved Their Families In Exile

In 1931, encouraged by the success of India’s first sound film, Alam Ara, its producer Ardeshir Irani decided to cast his net toward the burgeoning marketplace of south Indian movies. Enlisting his former assistant H.M. Reddy as the director, he launched Kalidas, a biographical film about the Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. As he sought to assemble a quality cast for the project, he received a suggestion for the female lead from K. Subramaniyam.

T.P. Rajalakshmi was, thus, cast in the first Tamil and Telugu talkie in Indian history. In addition to playing the heroine, Rajalakshmi sang four songs for the film and choreographed and performed a short dance sequence onscreen. Curiously, the film was defiantly multilingual. While Rajalakshmi spoke her Tamil lines, P.G. Venkatesan, who played the protagonist, uttered his in Telugu. Additionally, L.V. Prasad, who played a third principal character, delivered his lines in Hindi.

Right from her formative years, Rajalakshmi had been forced to wage a personal war against the Tamil Brahmin patriarchy she was raised in.

The novelty of Kalidas aside, TP Rajalakshmi’s real propulsion to screen stardom did not occur until she appeared in S. Vincent’s Valli Thirumanam in 1933. This was the first film she shot in Calcutta and thus began a three-year sojourn in Bengal (the film industry was yet to be regionally divided, and movies were shot in all languages in all the major cities), where she went on to appear in several commercially successful productions. She also fell in love with and married the actor T.V. Sundaram before returning to Madras with him in 1936. By this point, her popular performances had earned her the title ‘Cinema Rani‘ (The Queen of Cinema).

Buoyed by her endlessly thriving career as an actress, T. P. Rajalakshmi decided to launch her own production house. Sri Rajam Talkies was inaugurated in 1936 with the first venture Miss Kamala, which she wrote, directed, edited and appeared in. The screenplay was adapted, in turn, from the novel Komalavalli, which she herself had penned and published.

Miss Kamala was a feminist (or at least a proto-feminist) film by all possible historical standards. TP Rajalakshmi played the titular character of an upper-class woman who is forced to endure poverty and deprivation after being rejected by her own family for abandoning the husband she was forced to marry; Kamala reclaims her life and fulfils her ambitions independently (the attentive reader would not miss the biographical parallels here). A huge theatrical success, Miss Kamala affixed itself so closely to its maker’s heart that Rajalakshmi named her daughter after the eponymous film character.

The second film she directed, Madurai Veeran (1939), was immensely successful as well. Additionally, in the years between her first two directorial ventures, Rajalakshmi continued to act in some major film productions, including the Ellis R. Dungan-helmed smash hit Seemanthini 1936. However, soon after Madurai Veeran, this immaculate track record decelerated rather abruptly after the release of her third directorial project, Indhiya Thaai.

Activism

Right from her formative years, TP Rajalakshmi had been forced to wage a personal war against the Tamil Brahmin patriarchy she was raised in. As she grew older, her struggle continued against the gossip and seclusion that came with being an actress when it was considered a ‘dishonourable’ profession. Owing to her circumstances, she had always been resistant to the orthodox conservatism that surrounded her. It is, thus, hardly surprising that she used her liberated status and influence to fight for social reform.

Also read: What Happened To The Progressive Tamil Serials We Grew Up With?

In addition to her biological child Kamala, Rajalakshmi also adopted and raised a daughter named Mallika, whom she had rescued from female infanticide, a common practice in India. She also spoke openly in favour of widows’ rights to wear coloured sarees (the norm, then, for a widow, was to don white sarees alone for the rest of her life after the passing of her husband) and, even more controversially, for the time, their right to remarry a man of their choosing. She wrote books on these subjects and retained a lifelong commitment toward these ideals.

She also vehemently opposed the all-pervasive ill-effects of the Indian caste system. Having been exiled from her community for seeking a career in the ‘lower’ performing arts of theatre and cinema, Rajalakshmi relinquished any warm feelings she could have held toward the upper castes. She was a steadfast proponent and officiator of inter-caste marriages, earning even the respect of E.V.R.’ Periyar‘, the father-figure of Tamil rationalism, and a juggernaut anti-caste crusader and early feminist himself.

The last among her formidable opponents was, of course, the colonial government. During her days in the theatre, TP Rajalakshmi had managed to write and stage a few fledgling productions that were brazenly anti-colonial. Among her creations was the song ‘Parandhu pongada vellai kokkugala’ (‘Fly away, you white storks’), which led to a short stint in prison. Unfazed, she continued to stage plays that were critical of British rule in India. Indeed, this patriotic streak eventually led to the conception of her third and final directorial feature, Indhiya Thaai.

A devoutly anti-British picture, Indhiya Thaai (‘Mother India’; not to be confused with the 1957 Hindi film) was born out of TP Rajalakshmi’s associations with the Indian freedom movement by way of the Indian National Congress and her ideological reverence for Mahatma Gandhi. Always ready to push the envelope, the 28-year-old played the role of an older woman who was, possibly, the character the film’s title referred to. The British authorities were not pleased with the film’s instigative content and ended up truncating it severely. The film was also retitled, without her permission, to Tamil Thaai. The butchered final product was thus deprived of any chances it had at making a pan-Indian impact.

Final Years And Death

As if the colonial government’s resistance wasn’t enough, Rajalakshmi’s physical appearance in the film also stymied her career. As attested in a later testimony by her daughter Kamala, the primitive film audience of the early 20th century mistook TP Rajalakshmi’s artificially aged screen appearance for actual dotage. They assumed, thus, that the actress had finally grown old and lost her vitality. Patriarchy’s ugly demand for a woman’s eternal youth and beauty ended up being too strong a villain for even the indefatigable Rajalakshmi to overcome.

There are no known surviving prints of any of the milestones she produced, including Miss Kamala, Madurai Veeran and Indhiya Thaai, nor are there any traces of the first southern talkie, Kalidas, which she appeared in (Alam Ara too, was lost to the passage of time), or even her debut film, Kovalan.

Also read: How Tamil Cinema Normalises And Promotes Rape Culture

Her career prospects dwindled almost as swiftly as they had risen a little over a decade ago. After the release of Indhiya (Tamil) Thaai in 1939, Rajalakshmi appeared in just four films, taking up unmemorable supporting roles in modestly-budgeted productions. She initially lived a quiet and wealthy life before her financial condition worsened from years of inactivity. Soon, she was forced to sell most of her properties and adopt an unpretentious existence. She died in a rented house in Madras in 1964, at the age of 53.

Legacy

Like much of India’s heritage from the colonial era, almost all of TP Rajalakshmi’s films are lost today. There are no known surviving prints of any of the milestones she produced, including Miss Kamala, Madurai Veeran and Indhiya Thaai, nor are there any traces of the first southern talkie, Kalidas, which she appeared in (Alam Ara too, was lost to the passage of time), or even her debut film, Kovalan. Much of her legacy today is restricted to hearsay and a few surviving gramophone records that preserve her singing voice.

The indispensable role she played, among many other filmmakers, in the development of early Indian cinema, and her wide and varied contributions to theatre, literature, social reform, and to the freedom struggle are all now unfairly subsumed and condensed into simple one-liners: ‘She was the first Tamil and Telugu film actress’ and ‘She was the second female film director of India’.

As we approach T.P. Rajalakshmi’s 110th birth anniversary this year, one cannot help but wonder if any of her towering achievements, both onscreen and offscreen, will be remembered at all, far less honoured. If we are to undertake an honest effort at remembrance, we might be well-advised to consider her contributions outside the cinema sphere just as significantly as we do those within it.

She was a lot more than the Queen of Cinema, after all.

Vishnu Prasad has been a lifelong student of cinema and literature. He is currently pursuing a postgraduate degree in Cinema. He hopes to develop a unique voice through his art that can someday be weaponized to fight for social causes, and for the empowerment of the voiceless and the marginalized. When he is not torturing himself to come up with story ideas, he is usually trying to remember all his friends’ birthdays and buy them appropriate gifts on time. He wants to know everything there is to know, and tries to while being painfully aware of the fact that this effort will ultimately end in failure. He often acts like he is very mysterious and cool, but deep down, he knows he is fooling no one.You can find Vishnu on Facebook.

Featured Image Source: Feminism In India

Thank you so much for the detailed article. Wish you all success- Kamala TPR (Daughter of “Cinema Rani” T.P.Rajalakshmi