As Holi morning dawns, people are witnessed smearing rainbow colours on each other, splashing tinted water-balloons, and squirting one another with flute-sized syringes (pichkaris) filled with coloured liquid, thereby, enhancing the overall vibrant hues. This expression of spreading colours, delight and optimism all around is the fundamental soul and substance of the festival. Hence, the mythological, spiritual, cultural and social appropriation of the festival makes it carnivalesque and colourful. However, the way many women experience Holi is different from the amorous and idyllic projection of it. What is distressing is that some men tend to celebrate the festival discounting social and moral confines. For them, Holi is an untamed and unrestrained celebration; the festival licenses them to accost girls and women with arid colours.

The mythological, spiritual, cultural and social appropriation of the festival makes it carnivalesque and colourful. However, the way many women experience Holi is different from the amorous and idyllic projection of it.

In this milieu, the assignment of philosophising the above-stated transition requires that we identify hidden speculations, critically assess and comprehensively construct a conceivable framework for the recognised issue. Into the bargain, the enterprise of philosophising the issue attempts to discover answers to questions pertaining to What this transition suggests and Why and How does it transpire.

Also read: Holi has Become Yet Another Normalised Tool Of Sexual Harassment

What?

The glee and glory of Holi is evinced in the long-established slogan- “Bura Na Maano, Holi Hai.” (implying “Don’t mind, it’s Holi.” Or “Don’t take offence, it’s Holi.”). This standard slogan denotes the idea of a re-united celebration/ social peaceful union where, in the spirit of the festival, all mistreatments and grievances must be mutually forgiven. However, in reality, Holi celebrations get squandered when all lines of accountability, choice and consent get liquidated in the pretext of the slogan. This dereliction and fracture of the colourful spirit of the festival underscores the fact that the dynamism of Holi has merely been reduced to the manipulation of material colours, rather, misapplication of colours.

Explicitly, talking of the gendered nature of this misapplication, it is evident that under the shelter of the slogan, “Bura na maano, Holi hai”, men conveniently turn a blind eye to the stance that Holi signifies celebration of life, triumph of good over evil and correlative harmony. They handle the carnival in a destructive manner, thus, depressing the constitutional essence of it. They unleash hooliganism and consciously harass girls and women by ambushing them with powdery colours, dirt, grease, mud, eggs, tomatoes, water-balloons, etcetera. One may also profess that this misogynistic flavor of the festival oscillates and rationalises John Berger’s contention that “Men act and women appear.” Thus, when viewed through the lens of gender dominance, the festival of Holi loses its colourful-ness in the precise sense of the concept, instead, dwindles to becoming a festival of physical and material colours (nurturing the act of throwing and splashing colours, irrespective of responsibility and permission).

Why?

Why am I asserting that Holi is not a colourful fest for women but has transformed into a prohibitory festival of colours (chiefly emphasising the act of throwing material colours against consent)? A prompt answer to this question would be: because occasions of sexual harassment and oppression begin to stream down in and around the advent of Holi. Complete strangers smear women’s clothes with colours; coloured water-balloons are hurled at them; eggs, tomatoes, mud, etcetera are pelted at them. Adding to this, the stomach-churning and abhorrent strand of these actions is that women are strategically aimed at their breasts, hips and genitals. What matters here is that women’s experiences of the colourful festival are completely different from their male counterparts. For women, Holi is about exclusion, abasement and subjection.

If we scrutinise this strand of Holi as an array of gender dominance and unequal power dynamics, we grasp that this festival orbits around the theme of unqualified permission. Yes, bowling fistful of dry colours and dashing coloured water at friends and family is not an objectionable exercise, after all, Holi is inherently about colours, happiness and togetherness. However, the problem emanates when in between hues of pinks, yellows, greens, blues and violets surfaces hues of fear, apprehension and restricted mobility of women: all standard elements of a patriarchal structure.

In 2019, a hashtag campaign called #BlackAndWhiteHoli was instituted by Indian Women Blog. The underlying idea behind the campaign was to address the social problem of harassment and hooliganism that arduously unfolds during Holi. By alluding to the hashtag #BlackAndWhiteHoli, the advocators intended to protest against the unbridled normalisation of sexual harassment on the guise of “Bura na maano, Holi hai.”

The stills highlighted and interposed the flip-side of the festival. In the context of women, the soulful and sentimental value of colourful-ness, joyful-ness and playful-ness which has been congenitally associated with the festival evaporates when instances of harassment and humiliation surface. The true colourful spirit of Holi is marred by a lack of grace now.

Also read: Comic: Holi Is Not An Excuse For Sexual Harassment

How?

To a certain extent, this transition could be expounded in light of the notion of normalisation. French philosopher, Michel Foucault, in his book, Discipline and Punish demonstrates a sense of affinity between the phenomenon of normalisation and the idea of power. Normalisation in this context entails two slants, firstly, normalisation of the slogan- “Bura na maano, Holi hai.” Under the guise of this customary and consistent slogan, reckless men splash water on women, toss powdered colours on them, squirt coloured water from their water syringes and bombard them with sullied water-balloons.

Secondly, in a Foucauldian spirit, one may also behold that normalisation here encompasses the imbalanced thread of male dominance (powerfulness) and female subjugation (powerlessness) in the Indian society. Moreover, this thread plays a cardinal role in sustaining the cynical misapplication and abuse of the phrase, “Bura na maano, Holi hai.” Foucault centrally emphasises the role of the “idealised norm of conduct” that forthwith leads to the fabrication of a particular social condition. In a similar vein, if we appraise and further apply Foucault’s standpoint in the frame of the unequal social condition that prevails around Holi, we would grasp that the above-stated notion of “norm of conduct” in this milieu implies normalisation of the impression that the systematic attribution of men to “freedom” and women to “captivity” is the qualified normalised order. Thus, violence that perpetuates on Holi is not an unprompted and impetuous phenomenon; instead, it is a spin-off of a systematic and disciplined operation.

In plain terms, Holi has been lessened to being blatantly about a riot (uproar and havoc) of colours, omitting and disparaging its estimation of being a meaningful weave of absolute devotion and delight; courtesy and civility; balance and amity. Categorically speaking, harassment and humiliation in the name of Holi which has mightily materialised, ultimately dilutes the colourful-ness from this festival. Everything included, the essence and value of the festival has consumed a vile and immoral profile.

Categorically speaking, harassment and humiliation in the name of Holi which has mightily materialised, ultimately dilutes the colourful-ness from this festival. Everything included, the essence and value of the festival has consumed a vile and immoral profile.

In drawing things to a close, as a philosophical enterprise, let us mull over few questions-

‘Isn’t the true soul and substance of the festival utterly losing its stature?’

‘Is Holi actually a colourful celebration for girls and women?’

‘Does the festival hold a completely different meaning for them?’

‘Can we assert that Holi exposes unsaid social biases?’

References:

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing.

Aastha Mishra is a PhD research scholar at the Centre for Philosophy, SSS I, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Her areas of interest are Feminist Philosophy, Feminist Phenomenology, Feminist Ethics and Philosophy of Emotions. She can be found on Twitter, Linkedin, Facebook and Instagram.

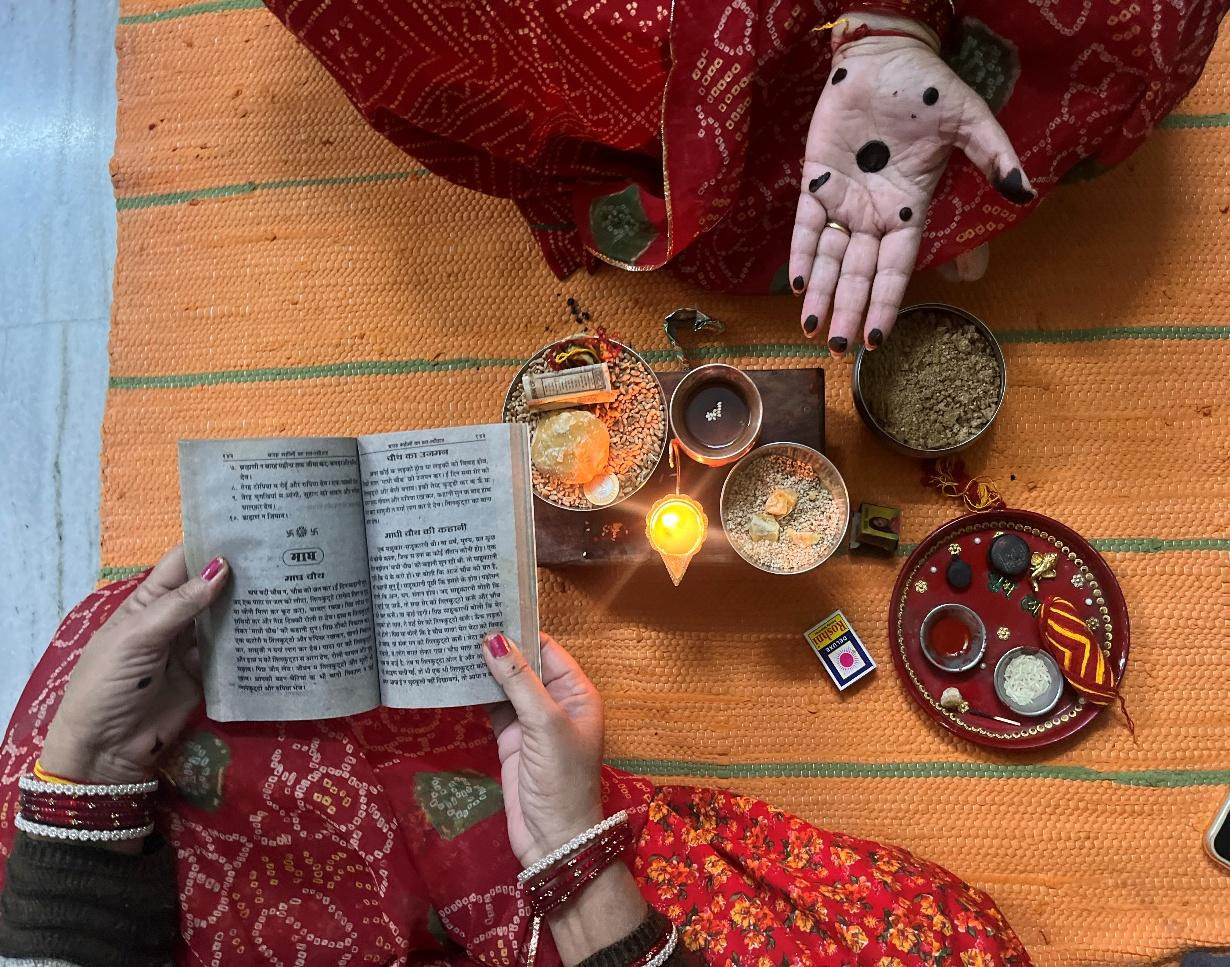

Featured image source: Indian Women Blog

Funny that you use white men as references to attack your own indigenous culture/festivals.