In a TED Talk given in July 2009, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about the “The Danger of a Single Story”. Circumfused with humor and unique cultural insights, Adichie’s speech made many unsettling and thought-provoking discussions. She said, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

Likewise, in Indian society, the single story we have of financially independent women is “liberation.” While being economically stable might ensure neutralised power dynamics between men and women and an acute escape from gendered division of assets, economic empowerment cannot and should not be studied in isolation to social empowerment. When Indian societal structure is underpinned by deeply patriarchal institutions like family and marriage, ‘independence’ contains multitudes.

Also read: Book Review | Mapping Dalit Feminism: Towards an Intersectional Standpoint By Anandita Pan

Shashi Deshpande’s short story A Liberated Woman is about a financially independent, popular, and supposedly modern Indian woman caught in a marriage about which she asks the narrator, “You tell me what to say about a marriage where love-making has become an exercise in sadism?”

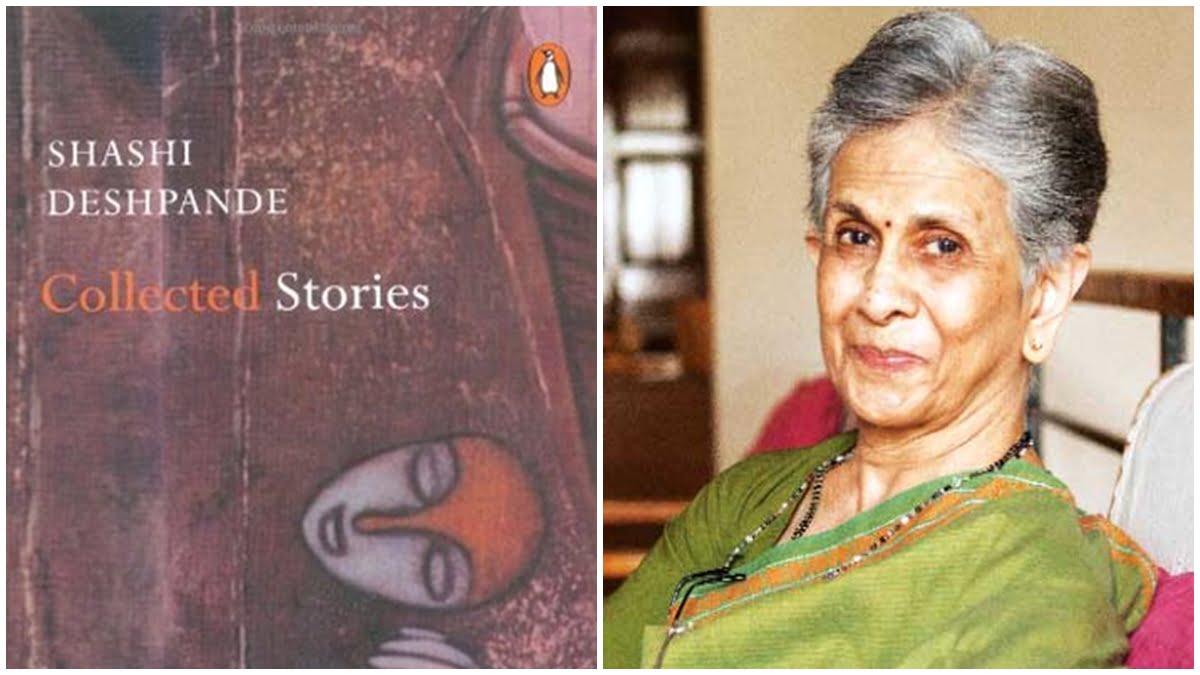

Sahitya Akademi winner and prominent writer Shashi Deshpande’s short story A Liberated Woman is about a financially independent, popular, and supposedly modern Indian woman caught in a marriage about which she asks the narrator, “You tell me what to say about a marriage where love-making has become an exercise in sadism?” Earning more than her lecturer husband, she persistently cosseted with a dangerous thing called a man’s ego. And eventually one morning she “woke up all bruised and sore and aching.” She says, “my first thought was that it was a nightmare I had dreamt too vividly. But there were the bruises…. all over me.” The protagonist of A Liberated Woman reasons it with, “It’s his way, the only way, perhaps, of taking a revenge on me for what I’ve done to his ego.”

A Liberated Woman is an ironical story, a grim and suffocating revelation of the dual reality that many Indian women are exacted to experience. These women are supposedly successful and self-standing, but are inwardly vassal to customary family roles, wherein acceptance, forgiveness, forgetfulness and silent capitulation is a long-standing tradition. A Liberated Woman reiterates that feminist ideal of economic liberation is hollow when it does not extend to social enfranchisement as well.

A discourse about women’s financial autonomy usually functions one-dimensionally, as Indian rural women are mostly ousted or ignored in these discussions. Women in rural area, working in informal sector, earn lesser than their urban counterparts, but earn nevertheless. These economically stable women make equal or more money than their husbands, and yet have negligible authority on their earnings. Given to their husbands, the money they earn do not guarantee them an equal position in the house. Moreover, these women are often subjected to horrific domestic violence, and other gender related crimes.

In the recently released movie Thappad, Netra Jaisingh played by Maya Sarao was a strong independent woman, a successful lawyer. Regardless of that, Netra was demeaned, ridiculed, and taunted by her top journalist husband. This is a cataclysmic consequence of the discrepancies in the institution of marriage, where the agency of a wife is influenced and constricted by that of her husband. In any case, a wife earning more than her husband is susceptible to demonising and/or petty mockery. Deshpande’s protagonist in the story A Liberated Woman said, “Listen, have you seen really old-fashioned couples walking together? Have you noticed that the wife always walks a few steps behind her husband? I think that’s symbolic, you know. The ideal Hindu wife always walks a few steps behind her husband. If he earns 500, she earns 400. If he earns 1000, she earns 999 or less. If he….”

Shashi Deshpande’s short story A Liberated Woman is an incisive commentary on India’s marital framework, and the same old tales of divorce, abandonment and rejection circumscribing a woman’s life.

Consequentially, for the both the protagonist of A Liberated Woman and Netra Jaisingh, the most monumental fear and the resultant incertitude was divorce – another subject that is overtly or covertly impacted by the regressive social constructs persisting in the Indian society – the genesis of which is, patriarchy. Divorce is directly proportional to a woman’s capacity and capability of sustaining a marriage, the sacredness and sanctity of which is more often than not the wife’s responsibility, to a degree that even financially independent women, the supposedly free ones, are in the constraints of this “Log kya kahenge” ecosystem.

Also read: Book Review: The Good Girls By Sonia Faleiro

Shashi Deshpande’s short story A Liberated Woman is an incisive commentary on India’s marital framework, and the same old tales of divorce, abandonment and rejection circumscribing a woman’s life. Deshpande challenges the notion of making financial independence a standard for emancipation, and in the process reveals the many myths of a liberated woman.

Nuzhat Khan is a student of English Literature at Jamia Millia Islamia. She is from Lucknow. She can be found on Instagram and Facebook.

👏 A thought provoking article.