Hannah Gatsby’s Nanette – makes a powerful exposition of the myth of reputation, one that has relayed for decades: “allegations of sexual assault or harassment must be made carefully since it can bring harm to the reputation of a harasser/assaulter man.” The import of reputation, into typical legal or public allegations of crime, further updates this sentence to: “allegations of sexual assault or harassment must be made carefully, reconsidered, challenged and debated; since it can bring harm to the reputation of a “good” man.” This precious pattern makes two false claims: first it clarions, “good” men cannot abuse, second, that allegations can ruin this “goodness” and everything that comes with it.

Hannah Gatsby’s Nanette – makes a powerful exposition of the myth of reputation, one that has relayed for decades: “allegations of sexual assault or harassment must be made carefully since it can bring harm to the reputation of a

harasser/assaulterman.”

This idea of reputation is then carefully protected by punitive law, giving every “good” man the brandishing right to slap a criminal defamation suit on any accusing “liar”. Reputation is so important that it has been read into the Right to Life and Personal Liberty under Article 21, as a fundamental right; which is how the judgement in M.J. Akbar vs. Priya Ramani finds itself tackling another right enumerated within Article 21, as it holds: “the right of reputation cannot be protected at the cost of the right of life and dignity of a woman as guaranteed in Indian Constitution under Article 21…”

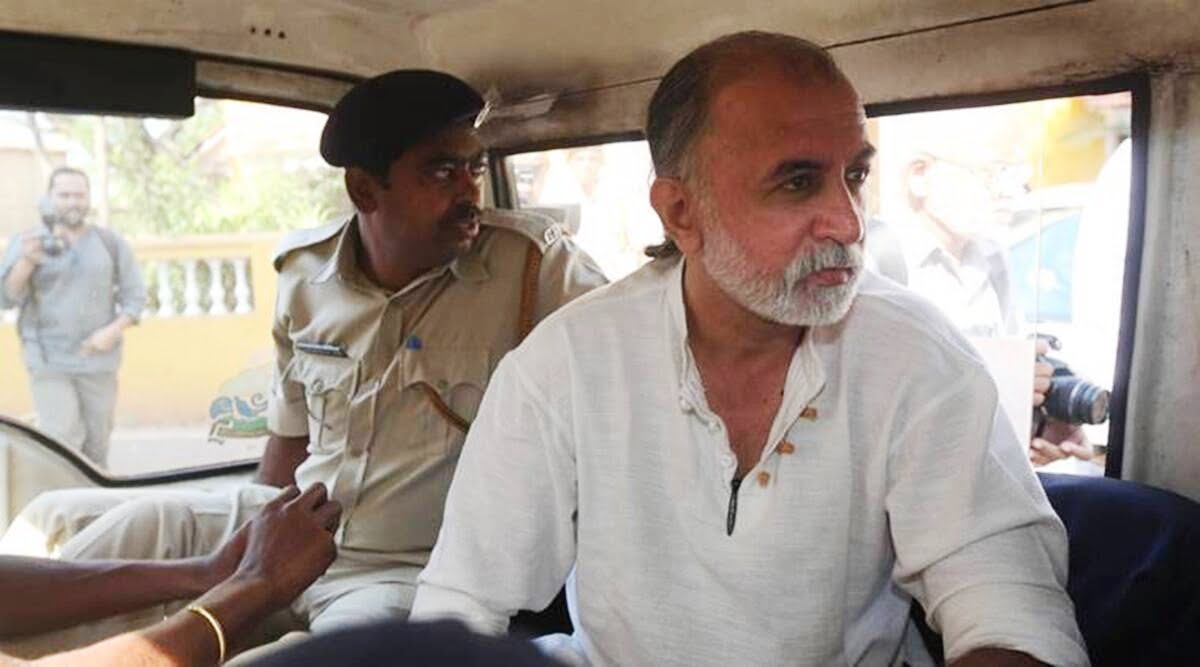

Also read: Tarun Tejpal Acquital: A Judgment On The ‘Appropriate’ Behaviour Of Sexual Assault Victims

In doing so, this verdict exposes a diametric between reputation and personal dignity that has long existed, it throws light at what was at the other end of protecting reputation: the compromise on dignity. But how did we reach this diametric? (The position where two legal claims are litigated against each other, the court then upholding one over the other.) When did we get to a place where reputation is an equal and opposite claim to dignity? And if reputation does measure-up against dignity, it is imperative that we revisit the idea of reputation itself. What is it? To whom is it valuable? Why do the rest of us not feel the desperate need to protect it?

When did we get to a place where reputation is an equal and opposite claim to dignity? And if reputation does measure-up against dignity, it is imperative that we revisit the idea of reputation itself. What is it? To whom is it valuable? Why do the rest of us not feel the desperate need to protect it?

The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines ‘Reputation’ as: “The opinion that people have about what somebody/something is like, based on what has happened in the past.” From this we know that reputation in itself if value-neutral, it can good or bad. In that case, can “good” reputation be a personal right? Something that we demand from others in society, knock on courts of law to order our reputation, even from those that we have injured? What does a defamation suit then pursue? Is it to avoid the red inks or achieve green ticks on our character report card?

What do men seek when they labour to falsify sexual harassment allegations? Is it to be proved as “good” men in society or simply “non-abusers”, and does that indicate that the two are synonymous? But when we defend reputation, we speak of a certain kind of repute. Like in the case of Priya Ramani vs. M.J. Akbar, and even Tarun Tejpal, it deals with a man of a specific stature, riding on a successful career as a marker of “good reputation” which automatically discharges the capacity to abuse. Further, courts seem to echo the “higher they rise, the harder they fall” argument when they scamper to protect successful men of repute, reiterating that there is a lot to be lost at the cost of fake allegations.

But when we inquire into what creates this “reputation”, the glaring observation is that it bases itself on dominant class, caste, and gender privileges, while DBA folks continue to be the “obvious” abusers. It is exactly these privileges, (not reputation) that allows such people to retain their power, despite allegations. Globally, harassers go scot free. In-house investigations are either not pursued, or pursued half-heartedly, featuring victim-blaming/shaming and men get on without a scratch. In other cases, abusers not only continue to hold important positions of power, but are offered promotions and awards. Only a sliver of the accused lose their jobs post-allegations, but this is always rightly so. Whereas the allegations on our everyday bosses, classmates, colleagues and relatives, only reside in hushed conversations of our catharsis about them. This tells us, that in reality, reputation means nothing; except for a naïve myth which creates the sole and single defence to silence women.

Also read: The Judgment In Priya Ramani’s Case Could Have Been More Progressive

The diametric created is ridiculous: Reputation vs. Personal Dignity. On one hand reputation demands goodwill from other people, which ironically, very critically rides on how you treat them. On the other hand, your personal dignity can be hurt without any of your doing, and creeps onto your bodily integrity, livelihood, and emotional wellbeing. But when sexual harassment/assault, and the silencing of it, is seen as an attack on personal dignity, it opens our imagination in understanding it as a method of control, humiliation and torture; and not about misread social cues, a momentary lapse of judgement or uncontrolled (hence, unintentional) sexual desire.

Criminal Defamation uses truth as a defence. A suit of defamation as a response to an allegation of sexual harassment/assault, therefore, replays the argument that women are liars, that a “good” man had to lose their standing in society “for nothing” or a scheming plot. Us, as a society need to build an appetite for sexual harassment investigations rather than stomach suits of defamation; the focus cannot be on character cleansing, but on the proper deliverance of justice.

Shreenandini Mukhopadhyay is a third-year law student at Maharashtra National Law University, Mumbai. She is interested in studying political theory, law and feminism.

Featured image source: Indian Express