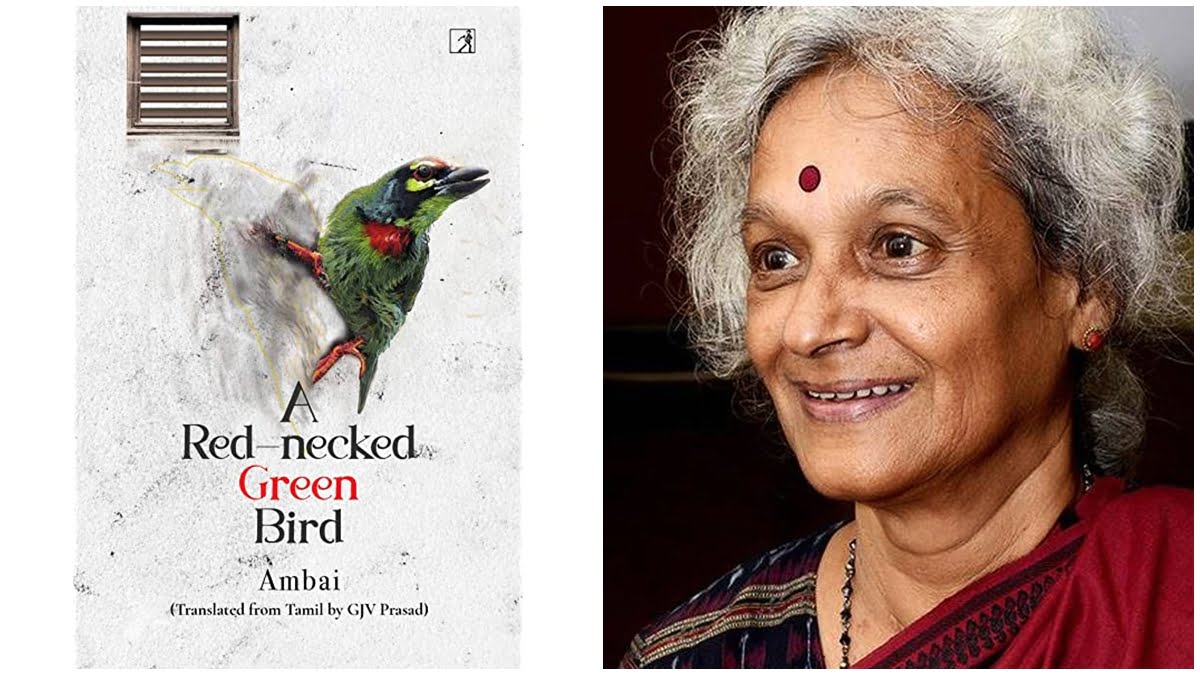

A Red-necked Green Bird (Simon & Schuster, India, 2021) is the latest collection of short stories by Ambai, pseudonym of much-fabled writer C. S. Lakshmi, translated from Tamil by GJV Prasad.

Exploring themes such as old age, abandonment, parenting and children, love, sexuality, solitude, and choice, the short stories in A Red-necked Green Bird are eclectic and nonconforming in equal measure. They are a testimony of Ambai’s prowess as a writer. Or, in her words, these stories are versions of herself.

Exploring themes such as old age, abandonment, parenting and children, love, sexuality, solitude, and choice, the short stories in A Red-necked Green Bird are eclectic and nonconforming in equal measure. They are a testimony of Ambai’s prowess as a writer. Or, in her words, these stories are versions of herself.

And GJV Prasad, the translator, has rendered the utterance of Ambai’s ‘many forms’ in the English language quite deftly. In its truest sense, he has, as Ambai mentions, taken “a seed from one soil” and successfully planted it in another, nourishing it with meaning by the excellence of his craft.

Also read: Book Review — Sick: A Memoir By Porochista Khakpour

The city and its stories

There is an incessant crow that would perch near the window when there will be a music program comparing Hindustani and Carnatic ragas, making the narrator of A Red-necked Green Bird wonder whether “it was a South Indian crow that had migrated to Maharashtra.” It could be a metaphor for the author’s dwelling in Mumbai. The city that she has successfully seeped into her narratives, making them richer, distinct, and diverse in the most Indian of ways.

An example of that is the story titled “The City that Rises from Ashes,” where the many incidents of bulldozing the city’s not-so-aesthetic parts to create paradise-like apartments are described. Taking Urmila, a seventy-five-year-old woman who dies of suicide, failing to make mends with the thought that her 90 year old mother-in-law would be transferred into an old-age home as she’s unable to gather strength to take care of her at this age, the story humanises the everyday struggles of caring and the labor of love. With Kamli, in the same story, who always “gaze[s] at the trees out of the front room window,” Ambai makes the most marginalised seen by sharing their stories in A Red-necked Green Bird, which are as relevant and contribute as much as anyone else’s in the changing face of Mumbai.

Further, what’s interesting about these short stories is that it not only features human conflicts at the forefront, it creates a dialogue between all elements that form the core of an ecosystem of which we are a part of, but consistently fail to register and appreciate their presence. They create and celebrate the most exacting of portraits of the human condition. And Ambai supplies these portraits in abundance in A Red-necked Green Bird.

What’s interesting about these short stories is that it not only features human conflicts at the forefront, it creates a dialogue between all elements that form the core of an ecosystem of which we are a part of, but consistently fail to register and appreciate their presence.

Also read: Book Review | Mapping Dalit Feminism: Towards an Intersectional Standpoint By Anandita Pan

Sounds of silence

The titular story, and the lengthiest of all, “A Red-necked Green Bird” is an exercise and meditation in practicing love by letting go. Vasanthan — a righteous man who even refused to take a fairness cream advertisement — leaves his wife Mythili and Thenmozhi, their adopted daughter with a hearing disability, to become a “Goonga Baba,” pleasuring himself a life of solitude in the mountains. Upon discovering him, Mythili frees him from everything, even “[f]rom the love between you and me as well.” It seems each character in these stories is begging to feel light and ephemeral. In “Falling,” we see the semblances of the freedom that Bauji in Rajat Kapoor’s Ankhon Dekhi (2013) in the 72-year old — “expiry time” — wife of Sathya feels when she “[w]ith Behag playing in her heart,” begins to slowly descend from the balcony of a hotel.

“Swayamvars with No Bows Broken” introduces us to a lonely Shanti after the demise of her husband, Arun. When her children try to convince her to “find a companion” on a website, she tells them that she’s seeing someone. The ‘concerned’ children were worried whether their mother had signed any papers. Though she’s seeing an old friend, “[s]he cannot forget Arun. Cannot erase him.” She “had known desire and longing,” but doesn’t feel that urge anymore; however, she wonders whether her partner would pester for sex.

With a cyborg as a principal character, “The Lion’s Tail” explores the terrain of desire in the modern era and asks whether our idea of intimate relationships is limited to humans alone. This story in A Red-necked Green Bird may remind people of Theodore falling for Samantha — an operating system, which comes with an AI-enabled virtual assistant — in Spike Jonze’s Her (2013). It also tables tangential discussions on language, “male-female gender divide” in our dimension, fluidity of sexuality, interpretation of dreams, and the limits of scientific temperament.

I loved all stories except “The Pond”. This story makes the use of the transformation of a man entering a pond into a woman to help him realise “fully what it meant to be a woman in this cruel period of the 21st century.” I fail to wrap my head around this. Do we need this trickery to convey this thought? I don’t think so. Because not only the story conforms to the stereotypical discrimination between a ‘man’ and a ‘woman’, it also erases violence experienced by people identifying beyond the gender binary or not conforming to gender at all. It solidifies the victimhood associated with women. Something that I believe we need to steer away from when we talk of equal rights and representation.