During the dreadful second wave that hit India in the months of April and May, social media websites transformed into SOS centers overnight. Thousands of people from all walks of life volunteered to assemble a system of resources, and information deployment online that, in hindsight, certainly saved a lot of lives. These volunteers were actively updating people on the availability of medical resources, especially in Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities.

But by the end of April, experts started noticing that COVID-19 had begun to penetrate even the most secluded parts of rural India at a very fast pace. And over 70% of rural inhabitants in India do not have access to an internet connection. Thus, in addition to the lack of government aid and unavailability of any healthcare infrastructure, most of rural India also could not seek health care information or aid online. This digital divide is just one of the many reasons that continues to intensify rural India’s struggle against COVID-19, especially in contrast to urban India.

Over 70% of rural inhabitantsin India do not have access to an internet connection. Thus, in addition to the lack of government aid and unavailability of any healthcare infrastructure, most of rural India also could not seek health care information or aid online.

From Urban to Rural

As of June 10, the weekly average of COVID-19 cases in India was about 100,000. In April, India recorded more than 6 million new COVID-19 cases. The official death toll for the month was about 40,000. In the month of May, India recorded more than 8 million COVID-19 cases. According to official data, 103,382 of these succumbed to the illness, putting the country’s total death count since March 2020 to approximately 363,000.

In April, rural areas of India accounted for 53% of total new cases and 52% of the total death count. By May, this had significantly increased. 66% of districts with a positivity rate of more than 10% were rural. In Maharashtra, for instance, 61% of the cases in the month of May came from rural districts as opposed to the urban 39%. Nationwide, the rural cases had jumped almost 20% from April. In Uttar Pradesh, 68% came from rural districts, up from 57% in April. In Odisha, 85% of the cases came from rural districts. In fact, in Odisha, COVID-19 managed to even reach the secluded tribe of Bonda. Bonda tribe is identified as one of India’s Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTG) and the spread of infection in the tribe would have dire consequences.

When we compare these statistics to the data coming before the second wave, the results are alarming. The shift from the urban to the rural is particularly evident in states that were worst hit by the second wave, such as Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh.

It is also widely speculated that these official numbers are far from actual statistics. In one instance, a BBC correspondent went to several villages in Uttar Pradesh and discovered that almost none of the people who have died due to COVID-19, either got treatments or official tests for the illness. Volunteers from the village informed BBC that most of the names of the deceased have failed to make it to official data.

Also read: Domestic Workers & Covid-19: Lessons In Dignity That Must Be Learnt

Second wave and rural economy

Chief Economic Advisor Krishnamurthy Subramanian as well as the finance ministry claim that the second wave will have muted economic consequences. However, these statements provide little reassurance when the nation still has not fully recovered from the economic losses that followed the first wave. The financial year of 2020-21 is Indian economy’s worst performance in 40 years. And unemployment has been on the rise since March 2020, and in combination with decreased wages, has already put a considerable strain on the working classes.

India’s rural economy consists of both agriculture and non-agriculture sectors. The non-agriculture sector includes construction, manufacturing, and retail amongst other industries. A considerable majority of India’s non-agriculture rural employment is in the informal sector. A study by Banaras Hindu University suggests that 400 million workers in India in the informal economy are at the risk of falling deeper into poverty because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the last week of March 2021 and the first week of April 2021, there were wide speculations of another national lockdown modelled on the 2020 one. Several migrant labourers, still recovering from last year’s lockdown, decided to go back home to their villages before the official declaration of, what was thought, an inevitable lockdown. But the agriculture sector is already overpopulated and this surplus labour could not be absorbed by the sector. What followed was the loss of non-agriculture based income in rural areas.

Poverty and debt was already plaguing India’s agriculture sector even before the onset of the pandemic. Over the course of the year, this seems to have intensified and is a looming threat to the stability of the rural economy. An IndiaSpend report outlines that while Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) markets have partially resumed, the lockdown and curfew restrictions have impacted its functioning. Farmers are desperate to sell their produce before it is ruined by the incoming monsoon season, however this has proven to be difficult.

Also read: The Govt Must Do More To Protect Pregnant Women From COVID-19

An IndiaSpend report outlines that while Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) markets have partially resumed, the lockdown and curfew restrictions have impacted its functioning. Farmers are desperate to sell their produce before it is ruined by the incoming monsoon season, however this has proven to be difficult.

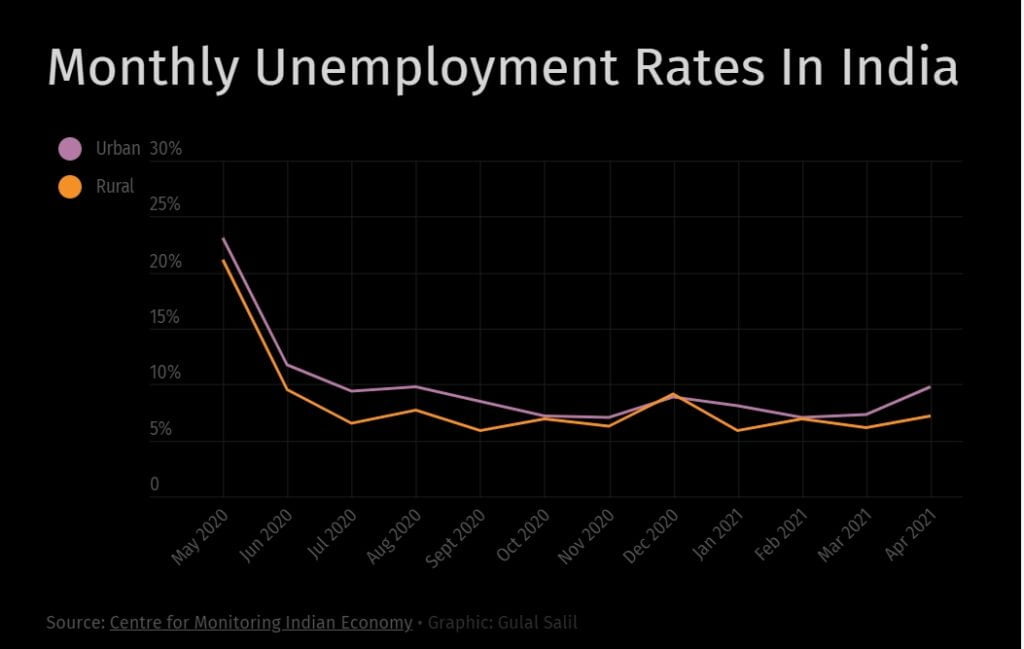

Contrary to official statements, economists had warned of the significant impact of the second wave on India’s rural economy. As highlighted above, supply chains have already been impacted. In a span of one week in May, rural unemployment doubled, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

Government Aid?

Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojna was announced in March 2020 and aimed to provide five kilos of rice or wheat per person and one kilo of dal to each family holding a ration card. While this would have ideally provided food security to households, in reality two states completely failed to distribute any grains and 11 states distributed less than 1% of their allocated amount of grains.

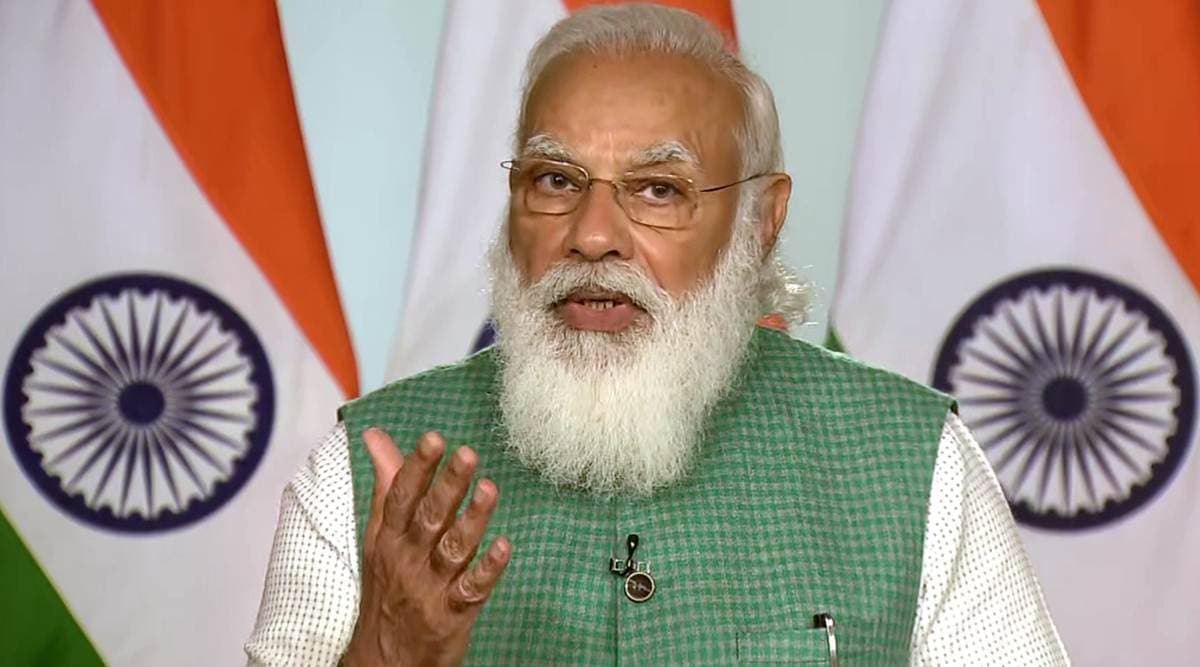

In May 2020, Prime Minister Modi announced the Atmanirbhar Bharat relief package. It was stated that this package would include INR 20 lakh crore, which is 10% of India’s GDP. Actual spending of the package have amounted to just 0.6% of the GDP. Although these packages were announced during and after the second wave, there seems to be no indication of another relief package after the second wave.

In addition to this, there is a complete collapse of the Indian healthcare infrastructure across both urban and rural geographies. The BBC in their visit to the villages in Uttar Pradesh discovered that almost none of the government clinics in these villages are functional. Volunteers informed the BBC that many deaths in these villages could have been prevented if supplies and beds were accommodated for the deceased in time.

In his speech on June 7, Prime Minister Modi announced plans to curb the decentralisation of vaccination drives and bring them under the control of the centre. This is a crucial development in the vaccine politics of the country. However, without the implementation of a strong and functional relief package, economists suggest that it seems unlikely that India would be able to recover from the second wave anytime soon. Furthermore, in order to prepare for future adversities, policy makers need to urgently shift their focus onto the country’s healthcare infrastructure, especially in rural districts.

Featured image source: India Today

About the author(s)

Halima is a History graduate from Lady Shri Ram College for Women. She has worked with grassroots political parties as well as international organisations. Her research interests are feminist theory, foreign policy, and area studies. She is currently doing a Master's in International Relations. In her free time, she passionately advocates for Phineas and Ferb songs for Grammy's.