She used to sit and rock with laughter at the lot of you. Love was a game to her. Only a game. It made her laugh, I tell you. She had a right to amuse herself, didn’t she?

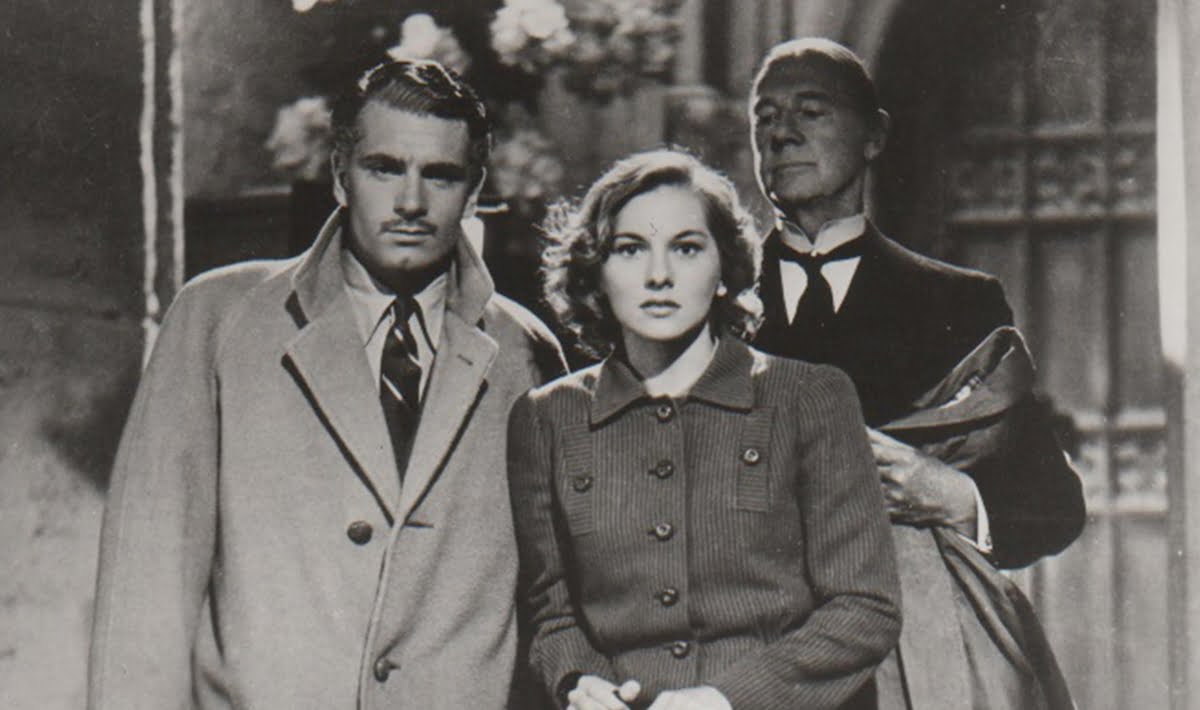

Mrs Danvers, Rebecca (1940)

Do you know about the 23-year-old nun whose name was Maricia Irina Cornici? She once began giggling, uncontrollably, during mass. What happened next is hardly surprising for someone in my research area – she was chained to a cross for three consecutive days for an exorcism, following which she died, or was killed, depending upon what terminology you associate with such an instance. Regardless, from a particular perspective of history, there is hardly a difference between killing women and women dying. The death of a woman has always been that ordinary, that everyday. Cornici had, for those keeping track, schizophrenia. And if the details of her killing aren’t enough to send chills down your spine, let me inform you this incident does not belong to the nineteenth century, this happened in 2005.

Also read: Reclaiming Hysteria: Medical Muses By Asti Hustved

Women laughing is a cause for suspicion in our collective consciousness. And so, it summons tragedy. Laughing women need to be controlled. There is something unruly about her guffaw, it sounds like a roar, it sounds like madness and it foreshadows chaos.

But women laughing is a cause for suspicion in our collective consciousness. And so, it summons tragedy. Laughing women need to be controlled. There is something unruly about her guffaw, it sounds like a roar, it sounds like madness and it foreshadows chaos. Well, exactly what can women be laughing about anyway? “A happy woman is a myth,” said that guy in that infamous monologue from Pyaar ka Punchnama. If you thought misogyny couldn’t contain a feminist statement, surprise! surprise! Then again many misogynist remarks have been reclaimed by feminists. Really, one of the most exhilarating parts of modern day feminism, confused men all around calling women bitch or prostitute or whore who then feel dejected when the women refuse to see it as derogatory. I feel for them. After all there is no greater sadness than a failed attempt at offending someone.

But jokes aside, finding humour in the face of oppression is an uncomfortable thought for many, patriarchy in particular; you see laughter of this kind finds its root in absolute sovereignty. That’s the trouble, the confined hallucinates freedom, and who has been able to control imagination? But come now, certainly there must be something he can do (haven’t we all heard there is nothing men can’t do, which hides this statement’s more sinister implication – there is nothing men haven’t done) and so he does, he makes sure she never forgets the cage, that she is constantly reminded of her confinement so as to conjure a schizophrenic fit and ultimately, her death.

Now here’s the trick, what if women bypass death? And the secret is, they have figured out a way, but more on this some other time because if I give in to elaboration now, the digression will make this long and I will lose the ever dwindling attention of readers on the internet. I intend to keep this short. So for now you can simply contextualise my convoluted statement within imaginative discourse, within women imagined, in other words, within fiction.

Can you call the eponymous Rebecca in Hitchcock’s film dead? You cannot, and in case you are somebody who can, you are left with an unexplainable discomfort, since she, not her death, looms large over this story, she seems to have a trade off with death.

So the question is, can you call the eponymous Rebecca in Hitchcock’s film dead? You cannot, and in case you are somebody who can, you are left with an unexplainable discomfort, since she, not her death, looms large over this story, she seems to have a trade off with death. And Mrs Danvers is the one who reminds the spectator of her eternal presence. She says, “Sometimes, when I walk along the corridor, I fancy I hear her just behind me. That quick light step, I couldn’t mistake it anywhere. It’s not only in this room, it’s in all the rooms in the house. I can almost hear it now.”

Also read: Feminist Laughter: A Form Of Resistance

And then when the specificities of her death are revealed in the end, her orchestration reifies a wicked victory, or is this plot twist a mere redemption of a murderous man and society’s legitimising of the killing of women? I think the latter viewpoint is reductive; Rebecca’s death cannot be carried out against her will, that much is evident from her characterisation.

As a consequence, her demonisation is predictable. Therefore, the words used for her either make her a monster or substantiate her monstrosity (as Sady Doyle would argue, monstrous representation of women oscillates between plain old misogyny and an intensely real fear of women’s power) – creature, snake, “incapable of love… or decency,” someone who would never be the ideal woman but will pretend to be (in order to manoeuvre around patriarchy), all add up to seeing women as the ancestors of Eve or the monster of Frankenstein. But here’s the thing, the category of monster in relation to women, much to dismay, is a productive one.

Monsters, as Nina Lykke asserts, are boundary figures, lying between the human and the non-human. Such an argument introduces a grey zone, a hybrid zone, which challenges the black and white logic of science. So she writes, “Being close to nature (my emphasis) in patriarchal thought, ‘woman’ may often be found lurking in the discursive spaces representing what lies between universal man and his non-human others. Therefore, any research which promotes the idea of a female feminist subject must be prepared to find itself situated with other monstrous enterprises in the grey zone between the human and the non-human.”

I stop here so you can think on your own about not only what I have written but also about things that I have missed or taken for granted while I prepare myself to watch the 2020 version of Rebecca and also find time to read Daphne du Maurier who wrote the original novel in 1938.

Srishti Walia is a research scholar in Cinema Studies at JNU. She can be found on Instagram.

Featured image source: Capa.com