Quentin Tarantino is an American film maker, writer and producer known for his violent cult classic films. His work is reflective of the postmodernist style. Such a style sets a known reliance on familiar images and appearances. It fills the viewer with a display of sentimental and nostalgic cultural code of identities, and a depthless simulation of ‘real’ without any substantial reference to actual historical detail or reality.

Tarantino juxtaposes the pieces in his movies in highly unlikely pairings, a collage of co-opted cultural references, art pieces or even ideas to form an entirely new product.

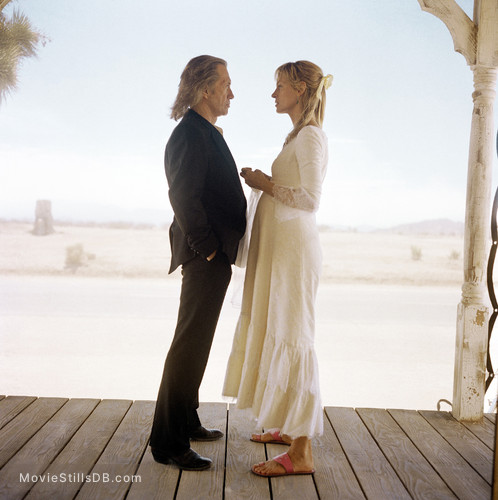

In Tarantino’s Kill Bill movies, Volume 1 is like a pastiche of the Kung Fu films of the East while Volume 2 involves a sampling of the classic Western movies. Tarantino’s cultural references in the Kill Bill movies demonstrate how the Eastern and Western culture has influenced each other over the years and the new style of action filmmaking is an inseparable blend of the two.

With Uma Thurman in the lead, the violence and fight scenes in both the movies are presented as a collage of different genres with some scenes filmed in black and white, some involving a great deal of dialogue, some barely incorporating speaking and a Japanese anime cartoon scene. Unlike other action movies, Tarantino’s gore and violence have a unique savour to them and seem tolerable with his transitional style of juxtaposing diverse cultural references.

the Kill Bill movies exemplify the male lens by co-opting a gendered enactment of revenge in which the female lead becomes a spectacle, catering to the gaze of the spectator who is made to identify with the male look. Thus, the determining male gaze projects its fantasy on the female figure, with her appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact

The groundbreaking contention around Tarantino’s Kill Bill is the co-option of violence in a seemingly feminist tone throughout the movies, touting a female lead with supposed agency, on a rampage venture to get back at her abusers after being comatose for a period of four years. She is seen striding her way through, with her exemplary professional fighting skills in pursuit of blood revenge.

A parallel and conventional narrative around the gendered concept of violence exhibited in the Kill Bill movies maintains that the images of women enacting violence in films, particularly onto men, serves to challenge the existing power relations between men and women as dictated by patriarchy by offering a sample of women in the seat of power.

Many would argue that a rape revenge drama like Kill Bill empowers the female viewers by engaging them in an energetic spectacle of violence and redemption, which admittedly from a first hand experience seems partially true. Female spectators do experience resistance through identification with women characters like Beatrix Kiddo aka The Bride, Uma Thurman’s role in the film.

However, it becomes crucial to employ a critically nuanced position to understand the perpetuation of female oppression in the cinematic concept of the male gaze. In her article Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey provides us with a diabolic concept of the male gaze reflected in cinemas. She argues that films stimulate visual pleasure by integrating structures of voyeurism and narcissism into the story and the image. These gendered structures are ones in which the former offers a visual pleasure by looking at others and the latter is used to derive a self-identification with the figure in the image.

While the exchange of traditional gender roles, particularly as they relate to the execution of extreme violence might strike a chord with feminist sensibilities, the film’s story arc places an undue focus on female beauty presented to us from a typical male gaze

In a similar fashion, the Kill Bill movies exemplify the male lens by co-opting a gendered enactment of revenge in which the female lead becomes a spectacle, catering to the gaze of the spectator who is made to identify with the male look. Thus, the determining male gaze projects its fantasy on the female figure, with her appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact.

Beatrix Kiddo is constructed as an angry, sadistic, skillful female avenger, who wears masculine costumes (sweat-suits, sport-shoes, jeans, leather jackets, boots), fights perfectly, knows far eastern fighting techniques, uses weapons (especially knives and swords like a samurai) very well, drives motor-cycles, gets out of a nailed coffin in a grave and kills dozens of O-Ren Ishii’s guards. The list goes on.

Also read: Male Gaze In Visual Media: The Fetishisation Of Women And Queer Characters On Screen

While the exchange of traditional gender roles, particularly as they relate to the execution of extreme violence might strike a chord with feminist sensibilities, the film’s story arc places an undue focus on female beauty presented to us from a typical male gaze. In the narrative of Kill Bill Vol. 1-2, some male characters like the Sheriff, the old man namely Esteban who owns a brothel in Mexico, the gravedigger and Budd (Bill’s brother), make comments about Beatrix’ femaleness, blonde hair, eyes and beauty.

In patriarchal ideology, the image of women can only signify anything in relation to men. The sign “woman” is thus negatively represented as “not-man,” which means that the “woman-as-woman” is absent from the film. It is this rhetoric that has been consistently gratified in the Bride’s character throughout the Kill Bill movies, by ascribing her with traditional masculine attributes, and providinga significance of rarity among her type

Throughout the movies, Beatrix is projected to the audience from the lens of the male agents that define her as a blood-spattered angel, co*ksucker, blonde pussy and so on while she continuously attempts to defy their assaultive gaze even in her weakest and most passive moments. Beatrix’s assertion of a female avenger is reiterated only when it conforms to the standardised ‘masculine perception‘ of an action hero.

Similarly, The Bride’s subversion from the tropes speaks of the normalcy of the tropes in themselves and highlights The Bride as an exception to them, the other. This tonality of otherness is implicitly displayed throughout the movie, when in Kill Bill:Volume 2, Beatrix is taken as a student by the sexist and xenophobic Kung Fu master Pai Mei. Before meeting Pai Mei, Beatrix is informed by Bill about Pai Mei’s sexist reservations for Caucasians, Americans and women.

Bill’s warning comes true as he daunts Beatrix’s womanhood with his male chauvinist attitude, only to realise that Beatrix is an ‘exception’ to his defined category of women and ‘deserves‘ respect as his prized pupil. As a reward for her ‘rareness‘, Pai Mei graces her with his benevolent sexism and rewards her by teaching her the Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique, which he deemed none of his former students capable of learning.

Within the biased gaze of the camera, the Bride is not portrayed in complete neutrality but rather as an unusual and attractive substitute to the trope – the exotic. The cinematic gaze often passes the sign “woman” as natural or realistic, while it is in fact a structure, code, or convention carrying an ideological meaning.

In patriarchal ideology, the image of women can only signify anything in relation to men. The sign “woman” is thus negatively represented as “not-man,” which means that the “woman-as-woman” is absent from the film. It is this rhetoric that has been consistently gratified in the Bride’s character throughout the Kill Bill movies, by ascribing her with traditional masculine attributes, and providing a significance of rarity among her type. It is this portrayal that has been upheld supposedly as one for female liberation and empowerment.

The second feminist contention around the movie is that its underpinning of the entire character of the Bride is that of a society-sanctified mother, rather than a woman of pride. While the Bride’s quest for vengeance indeed seems noble because she herself was violated, the aggravated validation and justness her revenge acquires is from the fact that her maternity was violated.

No matter how atypically powerful the Bride might be in achieving her goals, the story’s plot is completed only when she has fulfilled her societally designated role of rearing and protecting her child. The film’s valorisation for female reproductive biology traps the Bride in confined systems of motivation, by showing her adherence to a constrictive societal and gendered norm of motherhood

Such a narrative reduces the emphasis to a woman’s physiological capacity of bearing a child and perpetuates the overarching patriarchal idea of motherhood over any self-derived virtue. The Bride’s character motivations are self- defined responses to situations but are rather those defined from her female capacity for motherhood.

Furthermore, this essential plot is captured and delivered to the audience in the opening scene of the movie when the Bride is brutally beaten and isolated by her associates and left to die. She is shown pleading Bill, the patriarchal antagonist, saying “Bill, it’s your baby”, before she is shot. It imbues the audience with a sense of empathy for the Bride that is narrowly assigned to her maternity.

No matter how atypically powerful the Bride might be in achieving her goals, the story’s plot is completed only when she has fulfilled her societally designated role of rearing and protecting her child. The film’s valorisation for female reproductive biology traps the Bride in confined systems of motivation, by showing her adherence to a constrictive societal and gendered norm of motherhood.

The nature of womanhood, as explained by feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir in her monumental work, The Second Sex is defined entirely in relation and opposition to men, so women cannot achieve any real sense of self-fulfillment on their own. The film, rather than providing a self-derived and self-defined virtue to the Bride’s motivation for revenge, deduces her character’s motivations to her female physiology and in its direction style draws attention to the fact that the Bride is adopting practices which are traditionally reserved for men.

Thus, empowerment in this sense, is less defined by Beatrix’s tactful and skilled fighting capabilities, and more by the fact that she can perform practices that are traditionally reserved for men.

Kill Bill performs this sort of othering through its characterisation of the Bride’s agentive behavior, framing her depiction with not a neutral, self-created sense of power, but rather an appropriated “masculine” power. In conclusion, while the Kill Bill movies position itself as a landmark action franchise that supposedly liberates women and its audiences, the film only reinforces the idea that such a liberation is convenient to achieve only through compliance with the patriarchal societal structures that entrap women.

Also read: Film Review: My Happy Family Explores Women’s Agency To Choose Freedom

Thus, the inability of such films to achieve female liberation speaks of the necessity for future films to frame their female characters in broader contexts, providing them with real agency. In the attempt to display the vision of a liberated woman, films must establish her as an independent figure who is free to exist as her own being.

Featured Image Source: Tae Rang HA

About the author(s)

Mansi Bhalerao is an Ambedkarite feminist, an undergraduate at Miranda House. She is an aspiring student of Sociology, trying to navigate and assert her praxis.

Hello: I am sorry this is very misplaced, but I was not sure how else to reach you. I really liked your articles, and I was a particular fan of “The Ally Theatre of Savarna Solidarity” article: I wanted to leave a comment there but your comments section was closed. I am sorry to have to ask you this, but I could not find further elaboration on one line, which was: “burn Manusmriti to later celebrate festivals that are inherently casteist and exploitative towards the community”. I wanted to know what festivals in particular you were referring to? Is it to Diwali and Holi? Thank you so much for reading this, I hope you have a nice day.