Trigger Warning: Domestic Violence and Racial Abuse

On July 12, Italy was crowned the champions of the Euro 2020 football tournament, one which had gripped Europe and the rest of the world for the past couple of months. Italy defeated England in the English team’s backyard in a penalty shootout. Throughout the knockout stages of the tournament the English fans chants of “it’s coming home” echoed everywhere. The origin of the chant lies in the fact that many believe that the game of football was born in England, which is still heavily disputed.

However, whether England is the home of football hardly matters to the countless women when their male abusers make their homes a living hell, especially after their team loses in these major football games. The results of the Euro finals were overshadowed by the alarming rise of cases in domestic violence and hate crimes that followed. According to data, cases of domestic violence in the country rose by 38% after England’s loss. Furthermore, according to data shared by the UK’s National Centre for Domestic Violence (NCVD: incidents of domestic abuse rose by 26% when the English football team won or drew, compared to days when there was no England match.

Also read: Compulsive Bureaucracy & Media Obligation: Naomi Osaka’s Withdrawal From French Open

According to data, cases of domestic violence in the country rose by 38% after England’s loss. Furthermore, according to data shared by the UK’s National Centre for Domestic Violence (NCVD: incidents of domestic abuse rose by 26% when the English football team won or drew, compared to days when there was no England match.

In fact, a study conducted by the London School of Economics Centre for Economic Performance found that while domestic abuse decreases in the duration of the two hours in which the football game is being played, it increases exponentially in its aftermath, with the effect peaking 10 to 12 hours later.

Hypermasculinity in organised sports

Sports, especially those like football, that have way too much macho-masculine fervour attached to it often tend to have a gruesome flip side. For many, big tournaments like the world cup and the Euros is a time of celebration and a matter of national pride, however, a vast majority of women experience the darker side of these events.

While the violence and abuse post the games are often linked to and blamed on alcohol, let us be clear about one thing: Football and alcohol are merely excuses for the abusive behaviour of cisgender men. A win or a loss in a match does not enable abusive behaviour. Patriarchy does.

It enables and protects the abusers. It conditions them to believe they are entitled and have the right to display and let out their frustration the way they choose. Big hyper-masculine sports tournaments like these just exacerbate pre-existing abusive behaviours. Abuse is not a one-off thing. It is a choice that the abuser makes that stems from a sense of power, control, and the pre-existing gender inequality that patriarchy perpetuates.

Also read: Serena Williams Vs Carlos Ramos: Why Are Emotions So Gendered?

Fans of organised sports like cricket, football, baseball, basketball, etc are encouraged to be passionate to an extreme degree. Hypermasculinity is often the focus of many of these sports. If we take the example of football, on the field, players are ready to fight when there is a foul, dive and tackle and often get into fights with opposing teams and players. This aggression is often mirrored by the fans in the stands and after matches. Furthermore, the corrupt male-dominated authorities of the game have been woefully lacking in confronting this innate toxic behaviour.

History of violence

The surge in domestic violence cases post the Euro Cup final is however not a one-off incident. Researchers from UK’s Lancaster University who analysed domestic violence figures from England’s games in 2002, 2006 and 2010 World Cup found that incidents of domestic abuse were 11% higher the day after an England match. Furthermore, in 2018, during the football World Cup, NCDV released data that also showed an increase in reports of domestic violence by 26% when the English team played and 38% when the team lost.

Another recent study released in July this year examined crime reports in Manchester between 2012 and 2019. The study found links between the reports of domestic violence and the games played between English Premiere League football teams Manchester United and Manchester City. The study linked early kick-off times to increased domestic abuse and tracked how the violence decreased during the duration of play and gradually increased again later.

Racist Abuse, Hooliganism and Vandalism: Just sports-fan behaviour?

The Euro final not only saw a surge in domestic violence, but it also saw some of the worst instances of hooliganism and vandalism. Racist abuses were directed at the black members of the team, with players like Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho, and Bukayo Saka bearing the brunt of it. Angry England fans also beat up Italian fans outside the stadium and vandalised property.

The Euro final not only saw a surge in domestic violence, but it also saw some of the worst instances of hooliganism and vandalism. Racist abuses were directed at the black members of the team, with players like Marcus Rashford,Jadon Sancho, and Bukayo Saka bearing the brunt of it.

What is shocking here is that much of this extreme behaviour is pushed under a rug and dismissed as merely “sports fan behaviour” and “in the heat of the moment”, and thus, deemed excusable. The main reason for such distinction and bias is that this has a predominantly male demographic. Therefore, even extremely violent acts of vandalism and aggression are acceptable because of the demographic it caters to.

Violence and sports: A worldwide phenomenon

Cases of such aggressive fan behaviour is not just unique to the Euro cup final that England lost. This kind of toxic aggression by sports fans is a phenomenon experienced worldwide, be it the American Super Bowl, baseball, or any cricket tournament.

Data has revealed that domestic violence rises during AFL season in Australia. While in Canada, calls to the domestic abuse hotline in Alberta rose by 15% whenever a local team played. Meanwhile, a study conducted in 2011 examining 900 NFL games over 11 years found that domestic violence reports increased by 10% when a local team lost. This shows that, globally, a sporting outcome can lead to trauma and fear in the households of the so-called “avid fans”.

This further highlights the ingrained microaggressions of a misogynistic and patriarchal society. The violence reflects the power dynamics, a way for the abusers to exert control in their home, to feel powerful since they don’t have control over the outcome of the games. This raises serious questions about the culture and behaviour that organised sporting events promote.

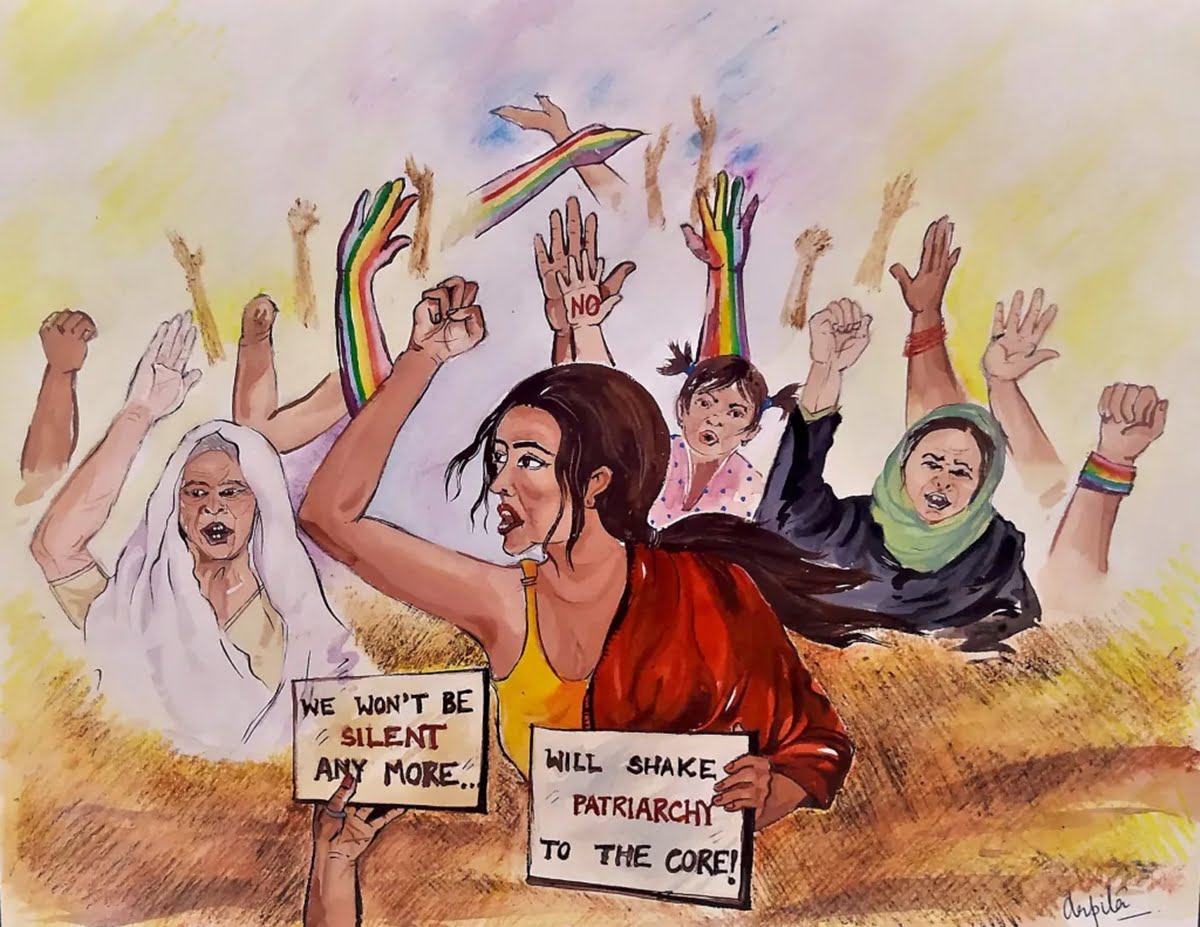

Featured Image Credit: Arpita Biswas/Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Shriya is a former student of literature and a multimedia journalist with an interest in sports and human rights. She can be found watching Shah Rukh Khan movies or listening to Ali Sethi and 90s Bollywood songs. She enjoys a good cup of black coffee multiple times a day and is often compared to 'Casper, the friendly ghost'.