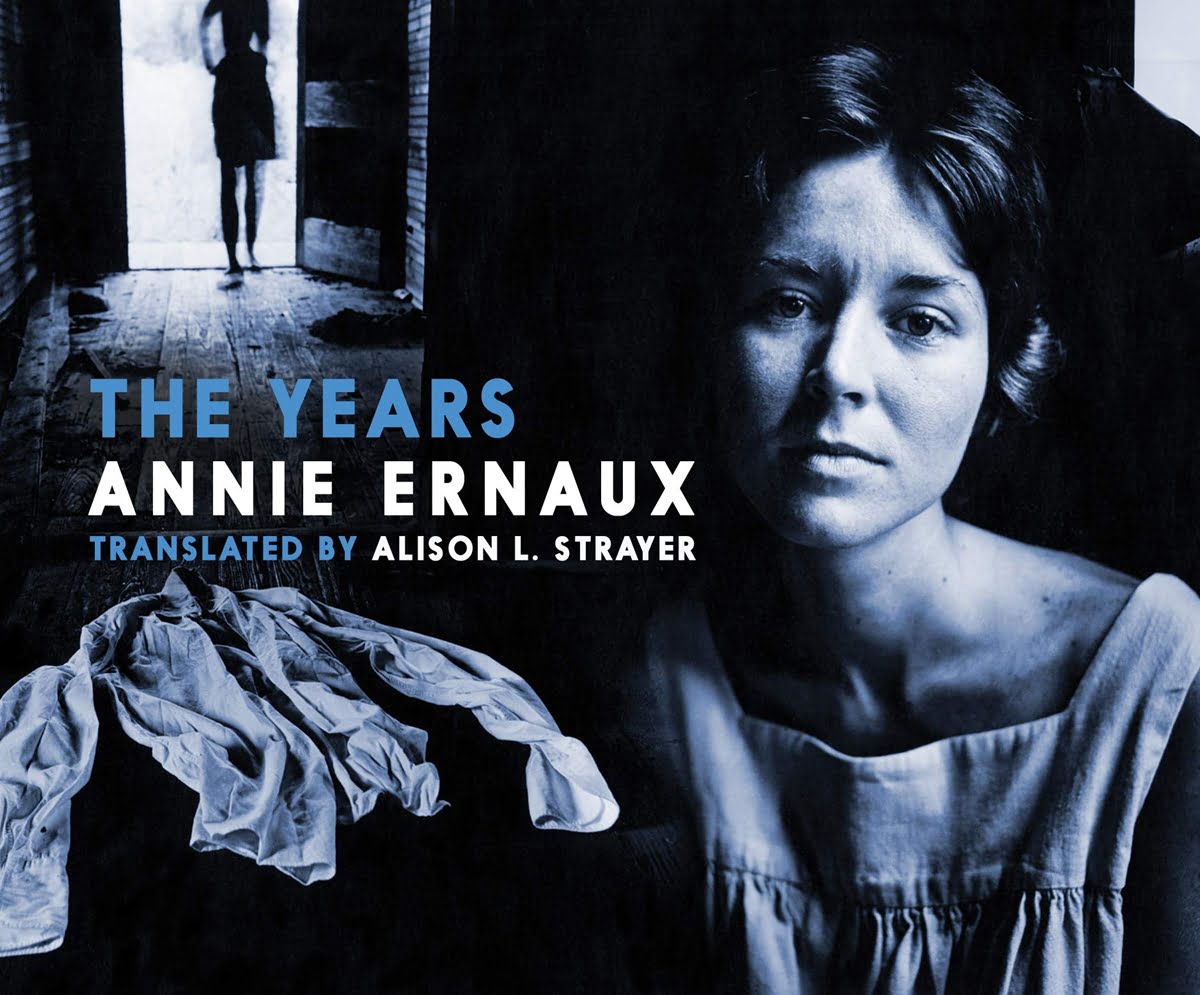

When an Instagram friend posted few lines from Annie Ernaux’s The Years (originally published in French in 2008 and translated into English in 2017 by Alison Strayer), I dug out the book from the Internet and pursued it immediately. The book was quickly read and long pondered over. Filled with big insights in small sentences, Ernaux’s work is a not-so-linear journey from her birth in 1940 to 2006, intertwining her private life with the political milestones of France and the consequent impact of these events on her generation.

Filled with big insights in small sentences, Annie Ernaux’s The Years is a not-so-linear journey from her birth in 1940 to 2006, intertwining her private life with the political milestones of France and the consequent impact of these events on her generation.

The movement of time – palpable and fleeting simultaneously- dotted with incidents of inner strife, was so poignantly put forth, that you can’t help but wonder how well she had kept her diary-writing for six decades. But what drew me to The Years is its long-drawn interior battle between a ‘liberated’ woman and modernity-induced standards, especially that of consumerism. In the auto-fiction, the unnamed protagonist’s skepticism of the hitherto unheard ‘progress’ that began in 1970s and consumerism that it triggered (which liberated and burdened women) is worth thinking about.

Also read: Book Review l Dragman: A Graphic Novel About A Cross-Dressing Superhero

At first glance, it seems The Years is all about collective experience of events that eclipses the personal, since Ernaux eschews ‘I’ and relates in ‘we’ or no pronoun at all; which reminds me of the following line that describes her parents’ generation– “From a common ground of hunger and fear, everything was told in the ‘we’ voice and with impersonal pronouns”. None of the characters including her sons and grandchildren, are named. She refers to herself as a nameless ‘she’. Through ‘she’ we get to know her marriage and divorce, her want for a lover and her fear of a technologized, sophisticated future. One of the most remarkable imagery in The Years is one in which she gazes at her naked aging body and reminds herself that this is the same body she lived in, at sixteen. But over the course of reading, one learns that ‘I’ is unimportant since formation of various and sudden subjectivities due to massive changes in political sphere can be anybody’s experience. The book excavates her and her generation’s life.

Fear of erasure

In The Years, stories are recalled through photographs, snapshots and things that she retained and are interspersed with local dialects, catchwords and slangs. As she says, the book was written out of fear of ‘losing’- losing her memories and herself amongst a newer, faster, easy-going generation who is concerned about nothing.

The May 1968 revolution of France set off a paradigm shift and ushered in ‘the new world’. But she is suspicious of the new ideals – individuality, equality and intense consumerism- that sprung up in the name of ‘modernity’. She finds the boom of women’s freedom that conjoined with commodification, baffling – “The perpetual display of their breasts and thighs in advertising was supposed to be construed as a tribute to feminine beauty”, she writes. She lacks her children’s dexterity with gadgets or the broad-mindedness to accept the ‘need’ to buy electronic items to look ‘modern’. Yes, modern equipment like washing machine and refrigerator have made women’s lives easier, but can everyone afford that? Doesn’t progressivism correspond with consumerism and commodification? Yes, sex and children outside of marriage have become normal and yes, abortion has been comparatively more destigmatised. But hasn’t consumerism created another set of standards that has widened the rich-poor gap? At 60, she is happy that her children’s generation needn’t perform ‘kitchen table abortions’ like she did, but is worried about their speedy lives and lack of reciprocity. Throughout her life she was looking forward to a progressive generation and when it comes around, she fumbles.

Motherhood questions

In a striking language in The Years, Ernaux compares her parents’ and her children’s generations. What was forbidden then is outright cool now. Although she acknowledges that it is the ‘modern’ turn in the century that has given her freedom to divorce, she is continually doubtful of her progress-induced motherhood. Modernity has brought in a second-shift- now she has to be career-driven woman who manages household as well.

She also ponders over the difficulty of sending children to expensive private schools to make them ‘modern’ and her a ‘good’ mother. She being a single-mother from working class background cannot afford that. But it is also the absence of a husband that makes her pursue writing and over time she becomes more of a ‘sister, friend and counselor’ to her children. She convinces herself that she needn’t think of her children often, but also fears the younger generation that increasingly holds their parents accountable unlike her own.

Through The Years one gazes at a web of confusions faced by a woman caught between two generations. Her ambivalence surrounding class background, career, education, lifestyle, motherhood and the new world order, is revealing; which makes The Years an exemplary work of intersectional feminism.

Through The Years one gazes at a web of confusions faced by a woman caught between two generations. Her ambivalence surrounding class background, career, education, lifestyle, motherhood and the new world order, is revealing; which makes The Years an exemplary work of intersectional feminism.

Also read: Book Review: Beijing Comrades By Bei Tong

The Years was shortlisted for Man Booker prize in 2019 bringing acclaim not only to Annie Ernaux but also to the translator Alison Strayer (and deservedly so). I consider it a feminist classic that is deeply wary of consumerism and the increasingly technologised future. As her final line- “Save something from the time where we will never be again”- sums up: this book is a tribute to the author’s struggling self. If you are looking for a quick, straightforward and intense read, savour this one.

Anju Mathew is currently pursuing PhD in English Literature from VIT, Vellore. She aspire to be a teacher who writes short stories occasionally. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram.