What do my favourite pair of shorts and our kitchen dustbin have in common, you ask? Why they’ve both been resurrected multiple times of course!

The garbage can in our kitchen sits pretty with dappled shades of molten plastic slapped onto it to keep it from becoming garbage. It is now made up of waste in ways more than one.

My favourite pair of shorts has always been the one with the colourful patches of cloth sewn deftly onto them because mum put her sartorial talents to full use. And finally, when, after years of regular use, it was time to bid them goodbye, they only went as far as the storeroom to be transformed into a “nyata” (a rag meant for wiping surfaces). And so, many of my clothes have stayed in our house as long as I. Some even longer, having been graciously handed down to me by my brother, cousins, and aunts.

Also read: Fast Fashion Is A Feminist Concern. Here’s What You Can Do

In our house, articles of clothing and material things are as permanent a part of my family as are its people. Having observed this approach as an adopted way of life, I have come to believe in two things: first, I can value things for much more than the immediate purpose they serve. You see, we’ve sat at our dinner table with enthho haath, neck-deep in nostalgia, as my dad recounts the story of how my grandfather sat at his chest of tools and repaired our wardrobe’s lock with nimble fingers. I have seen my father often lug the pendulum wall clock to mechanics, arduously resuscitate it, and wind it every Sunday so that it continues to chime as it has for decades.

All the objects in my house have a history and I have been taught to respect that. They are no less than people, if not more since they contain their own essence in addition to that of the people who have used and cared for them. This brings me to the second observation: objects are rarely use-and-throw. It is deplorably simpler for me to form bonds with items of regular use than it is with people, for where else would I find this reliability or permanence? Isn’t that why we seek solace in rewatching the same sitcom endlessly, our place fixed in the characters’ journey, even as the stability of their stories contrast the unpredictability of ours? Despite the risk of seeming materialistic, my relationship with people, their memories, is firmly etched in the things we use together: in shared times and spaces.

Material things, therefore, mean much more to me than the immediate purpose they are meant to serve. I tend to think twice before changing my phone or parting ways with a pair of shoes that have long lived their life because they are made up of memories. I reminisce about a friend’s passionate reviews before I invested in my phone; the phone has since outlived my friendship with its reviewer. I remember the straps of my shoes giving way at the Esplanade junction, leaning on my friend’s arm, and hobbling to the nearest cobbler; my shoes have since been stitched with anecdotes.

Also read: Sustainable Fashion: Exploring The Possibilities Of Thrift Shopping

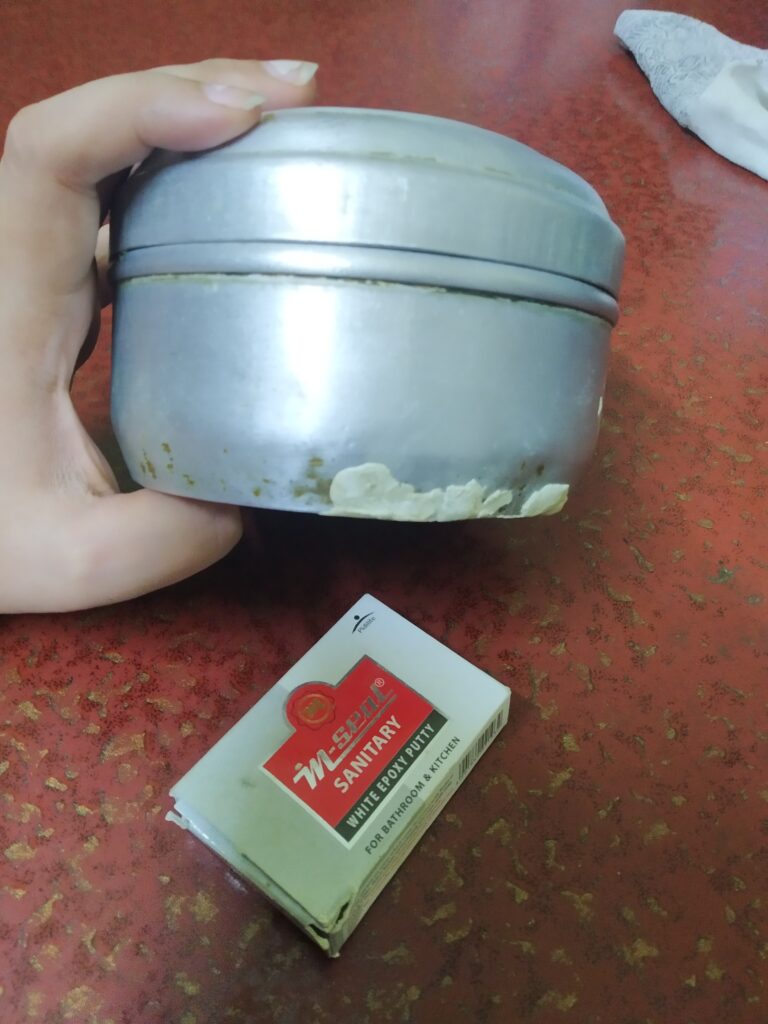

My attachment to things and nostalgically holding on to them (hoarding, as my mother would call it), also helps me practice The Art of being Thrifty. My refusal to part with things leads me to devise alternate uses for them or repair them and give them a second life. I have been able to imbibe this way of life by observing my parents. My father had to introduce me to Pidilite M-Seal (a kind of sealant) only once, for me to find a use for it everywhere. Most recently, I took it upon myself to mend my mother’s aluminium containers that had holes with this putty. Similarly, a mishit doi bhaad turns into a flower pot. My grandmother’s old cotton saree doubles as cheesecloth. A little effort on my behalf leads to the conservation of the material things I own as well as of all the potential resources and energy required to create the replacement I would have bought from the store. More personally, in true thriftiness, I also save considerable money.

I do not doubt that this could have been described in a much more scientific way, featuring all the technical terms that environmental scientists would use. However, the absence of that language, dear reader, is to also show how a lifestyle of attempted frugality would look in the everyday*. It is not a substitution of scientific information—for that has no substitution—but a demonstration of the quotidian as scientific. Being thrifty has been a part of so many communities and cultures for decades now. Most of our roots advocate living sustainably; it’s not a new concept. This article is an attempt for us to consciously adopt and practice it. This is a call to arms for thrift to make a comeback, not as a fad, but as a crucial tool for sustainable living.

*Although I must acknowledge that to preserve and repurpose comes from a position of privilege because I have the means and space to store things I already possess.

Featured Image: Shreya Tingal for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Dipshikha completed her Masters in English in 2020 from The EFL University, Hyderabad. Her primary area of interest is the intersection of Queer Studies and Film Studies. She is currently enrolled in a film appreciation course at FTII, Pune and works as a researcher at Arth Early Learning Spaces, Kolkata.