Mainstream media is tied together at the seams with standards and ideals that are, in many ways, ‘Upper-caste approved’. It comes as no surprise then, that this hostile environment refuses to fully appreciate the achievements of Dalit-Bahujans. Media and the industry, dominated mostly by the upper castes are attempting to erase Arivu, the lyricist behind Enjoy Enjaami and Neeye Oli yet again; and with him, the seeds of resistance that his songs talked of.

Perhaps the song itself predicted this subsequent invisibilization that Director Pa Ranjith accused Rolling Stone India and AR Rahman’s music platform Majjaa of – this cycle of theft and rebranding by giving the song a different face and removing Arivu entirely continues as the lyrics echo ironically: “Nan anju maram valarthen / Azhagana thottam vachchen / Thottam sezhithalum en thonda nanaiyalaye” (I planted five trees / Nurtured a beautiful garden / My garden is flourishing, Yet my throat remains dry).

This cycle of theft and rebranding by giving the song a different face and removing Arivu entirely continues as the lyrics echo ironically: “Nan anju maram valarthen / Azhagana thottam vachchen / Thottam sezhithalum en thonda nanaiyalaye” (I planted five trees / Nurtured a beautiful garden / My garden is flourishing, Yet my throat remains dry).

Rolling Stone India decided to conveniently erase Arivu from its cover even as other Tamil artists such as Dheekshitha Venkadeshan aka Dhee and Shan Vincent de Paul’s faces were placed prominently on the same cover. The cover story touches upon how songs such as Enjoy Enjaami and Neeye Oli became popular: both projects, for which Arivu has contributed significantly to: as the singer and lyricist and as the lyricist, respectively.

Earlier, a poster that featured just DJ Snake and Dhee as the former created a remixed version of the song for Spotify Singles, also made news in how it (again) erased Arivu. When the Times Square featured Enjoy Enjaami in June this year, it was the first time an independent Tamil song found its way up to the prestigious billboard, but, no prizes for guessing, Arivu, whose intellectual labour and history of oppression went into the making of the song, was invisibilised. The billboard only featured DJ Snake and Dhee. The remixed version reads ‘DJ Snake & Dhee: Enjoy Enjaami feat. Arivu & Santhosh Narayanan’.

Also read: Enjoy Enjaami: Deconstructing The Politics Behind Arivu & Dhee’s Latest

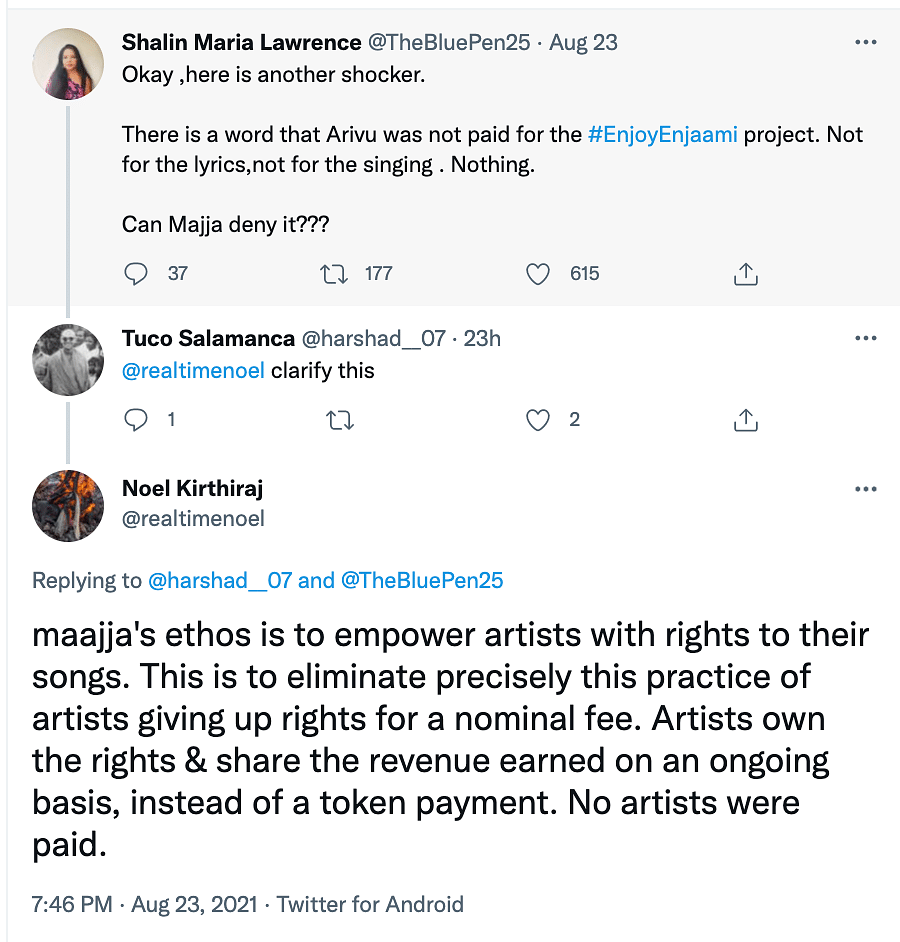

And now, at the heels of the Rolling Stone controversy, reports indicate and Noel Kirthiraj (one among the owners of Maajja) confirm that the platform did not pay Arivu for this work in Enjoy Enjaami. Not to mention how the streaming giant YouTube does not credit Arivu for the lyrics of the song, despite the song being among the most popular songs to have been released on the platform. Launched in March 2021, Enjoy Enjaami currently has over 320 million views on YouTube yet the tag says ‘Dhee ft. Arivu’.

Underlying this erasure, this outright dismissal of the song’s meaning and cultural significance, might again be an attempt at keeping Dalit artists such as Arivu ‘in check’. As I click on the song’s poster again, I notice not the community the song sought to bring together, but the place Arivu occupies in the still – on the side of an ornate gold chair occupied by Dhee, and now he’s entirely out of frame.

Erasure is the act of corroding identities and records, silencing minorities from partaking in the formation of the idea of ‘society’ and its cultural and historical lineages. Undoubtedly, as Anton Allahar notes in a paper, it goes hand in hand with supremacy and enslavement, carefully eliminating any complimentary idea of the social Other, exoticizing them in order to create clear divisions and finally, sometimes leading to appropriation.

However, with the background of the power imbalance between Dalit-Bahujan and Upper-Caste people, appropriation implies the act of sanitizing voices – whether it be Arivu’s songs, or what meagre stories begrudgingly recorded in textbooks and museums, it becomes apparent that they do not matter unless an upper-caste person retells it.

They do not gain recognition until they have a more ‘appealing’ label attached – think of what we consider ‘good taste’ in cultural artifacts in a Brahmanical society to be: the ghee, the silk, the gold, the Bollywood movies with, as Nishant Roy Bombarde is noted saying for The Indian Express, “‘good-looking’ lead actors” that people look for by “casually confirm(ing) if a certain surname was upper caste.” He says before, “A badly dressed person is called bhangi. Anything that was disgusting is dismissed as chuda-chamar.”

If Arivu doesn’t receive his due recognition, then the song and this instance becomes another example of a suppressed community’s cultural heritage being appropriated by upper-caste communities. As the song employs the use of Oppari music sung at funerals by lower-caste people, which Arivu calls “the actual hip-hop of India,” removing his name converts the song into something to be worn and discarded. It no longer pays tribute to the brutal history of oppression the song dutifully included. Tweaked for ‘proper consumption’, art by Dalits has always been cherrypicked for its ‘acceptable’ aspects – somewhat like the ‘tribal’ art that hangs in households which actively look down on ‘tribal’ food.

Dhrubo Jyoti points out that “the primary and middle-class textbooks are replete with references to upper caste leaders and reformers — think Gandhi, Rammohun Roy, Vidyasagar, Tilak — but omits anyone else.” Dalit-Bahujan successes and achievements are selectively exterminated – These seemingly unrelated instances display clear symmetry in its pattern of caste-based hierarchies and its functions – erasure and disgust are deeply entrenched. Arivu’s instance is not a singular happening and by the looks of it, neither will it be the last.

Only recently, Vandana Katariya (a Dalit Indian Hockey player that played as a part of the Indian team at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics) and her family was harassed with casteist abuse because the team failed to qualify or ‘achieve’. Her past successes forgotten; she was made to take the brunt of it all. When we question why, we bitterly recount Rohit Vemula’s statement – “My birth is my fatal accident.”

Also read: In Conversation With Anti-Caste Artiste Arivu: Rapping For Equality

Oscillating between having to achieve too much to be recognised, and never being recognised for it at all, this unstable position is centuries old. With no limits and no reason, they become targets of scrutiny at all times. Shravankumar Limbale mentions in Towards an Aesthetic of Dalit Literature that Dalit writings have often been accused of “obscenity and sensationalism” – tagged as being propagandist, ironically said to be claiming for a ‘popularity’ that they never actually receive.

This unwillingness to engage with Dalit-Bahujan art may also stem from an obsession with what we see as ‘Universal’ or ‘Canonical’ and how we define it – any authority on any subject must only rest with Upper-Caste people. An associate professor at IIT, Vipin P. Veetil, recently resigned and restated the Brahmanical supremacy that dictates the workings within elite institutions of India. Explaining the whitewashing of the horrific experiences of marginalised communities, Omaiha Walajahi comments, “reservations for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes still spark a controversy and accuse these groups of stealing their seats or not working hard enough to get where Upper-caste people are.” This monopoly has always been of the upper castes. Dhrubo Jyoti relates it aptly: “Remember the traditional practice of pouring molten lead down the throat of any Dalit person trying to learn Sanskrit.”

Such interactions have now seeped into subtler forms as well – while forgetting to credit artists from oppressed communities is one way, Bombarde also recounts that certain evidences that can be found in Bollywood, for example, also lie in other happenings: “People forget your work or how they miss inviting you to functions, or the sheer lack of work offers despite having proved your calibre.” They also face the threat of having their work entirely stolen – Noel Didla mentions an article by The Hoot from May 2016 as being “uncannily similar to the open letter published by SAVARI in 2014” – the work of Dalit Bahujan women “stays in the name of a male author in The Hoot”.

The physical segregation of having to live outside village boundaries has now changed to a divide on the non-physical land of ‘insiders’ of any industry. And inscribed in this apartness, Alok Mukherjee says in Limbale’s book, is “inferiority.” Dalits have been made to work for the Upper-Castes: they build the hearths, the houses, they till the lands, but they cannot escape the preoccupation with discrediting the work done, an almost arrogant belief that UCs are entitled to not crediting in the first place.

When non-Dalits do support, Limbale says, they resemble “the presence of a patron,” seeking to “put forward ideas to guide them.” And as Didla draws our attention to, these “empty solidarities” have been unable to change any material aspect, they only “continue to perpetuate violence in the most intellectual ways and spaces possible.”

The power, after all, of dictating the narrative rests in their hands. When non-Dalits do support, Limbale says, they resemble “the presence of a patron,” seeking to “put forward ideas to guide them.” And as Didla draws our attention to, these “empty solidarities” have been unable to change any material aspect, they only “continue to perpetuate violence in the most intellectual ways and spaces possible.”

On this one case at hand that prompted this article, we wonder, who is at fault? The companies and upper-caste collaborators that forget to credit Arivu, a Dalit artist, or the caste riddled consumer base which won’t accept music that tells them of their ignorance until a figure from their community they deem ‘proper’ tells them to do so?

This period of heated debates and rapid tweets will subside…and then what? Will it be enough? When public outrage cools down, will we fight still against caste oppression and try and prevent it from happening again? Or will we reward ourselves for this singular instance and continue ignoring the ones who did not garner millions of views for there to be an outrage?