Anjali Joseph’s fourth novel Keeping in Touch (Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Pvt. Ltd., 2021) is not only a tale of modern-day love, but an exploration into the deepest recesses of one’s being to understand what a human connection is all about. After reading this book, one is bound to agree with her mentor Amit Chaudhuri, who praises Joseph saying, “she attends to questions for which not every novelist is equipped.”

Anjali Joseph’s fourth novel Keeping in Touch is not only a tale of modern-day love, but an exploration into the deepest recesses of one’s being to understand what a human connection is all about.

Feminism in India got in touch with Joseph to discuss the book.

Also read: Interview With Dr Manjima Bhattacharjya, The Author Of Intimate City

Edited excerpts:

You mentioned in an interview that you repurposed a short story you wrote as an eight-year-old for this novel. What made you unearth a thirty-five-year-old material, and what insights it had that you found still relevant?

Anjali Joseph: I didn’t unearth that story, as such, but the title stayed in my mind, and for some reason it made its presence felt when I was writing a short story in 2015 that turned into the novel’s opening chapter. I guess I just liked the name ‘Everlasting Lucifer’ for a lightbulb.

The principal characters in your book are in their late 30s, experiencing a newfound, teenage-like love. What drew you into the worlds of your characters Ved and Keteki?

Anjali Joseph: Falling in love is probably always teenage in ways—the awkwardness, the uncertainty. But there’s also a characteristic of late-30s love that I’d noticed, which could be summed up as the idea that a person by that age has a set of behaviours to help them cope with things they find difficult, whether that’s intimacy or rejection. Sometimes letting go of the belief you know how to organise your own life is necessary if something new is to happen.

Early in the book Ved says “you can never go home again”. Besides exploring modern-day relationships, the book is also about ‘keeping in touch’ with one’s idea of a home, be it a person, place, state of mind, and how one wants to find ‘everlasting’ happiness in that thing. Would you agree that it’s one of the functions of the book? Or is there nothing like enlightenment of this sort in life?

Anjali Joseph: It’s one of the things that intrigues me most: Does an enlightened person ever snap at their family? Show a moment of vanity? Where does the humanness go? But for most of us, I don’t imagine that enlightenment is either that far away or, some kind of, permanent external shift that takes place. It’s just a very powerful reorientation. You might lose awareness for a moment or a few hours, and then drop the things you’ve been entangling yourself in again. In the novel, the idea of keeping in touch is definitely keeping in touch with that quiet inner perspective that isn’t really interested in the external drama of your own life. The more one connects with that, the easier it is to connect with other things and people. I think both the protagonists in the novel are seeking that sense of home, Keteki more actively than Ved.

‘In the novel, the idea of keeping in touch is definitely keeping in touch with that quiet inner perspective that isn’t really interested in the external drama of your own life. The more one connects with that, the easier it is to connect with other things and people. I think both the protagonists in the novel are seeking that sense of home, Keteki more actively than Ved,’ says Anjali Joseph.

Did this contrast—manufacturing a bulb that lasts forever in a strange land that often defies scientific temperament and explanation—appeal to you when you began writing the book? Or was it a measured step to explore the consequences of this convolution through this story involving two people unlikely to fall in love?

Anjali Joseph: I don’t know that I thought of it as a contrast. I loved living in Assam, and I was fascinated by the different spiritual traditions and perspectives on spirituality that I came across, whether goddess worship and tantra or the Vaishnavism of Xonkordeb. I loved the fact that Assam does not give itself up easily to a visitor in terms of understanding its culture—it is a beautifully complex and sophisticated place, infused with art and irony. And of course, that complexity also makes it a great setting for a comedy of errors with an outsider such as Ved.

Would you like to share why you felt Assam and London were the best-fit places for this story?

Anjali Joseph: I think I’ve answered half of this question. As for London, and Suffolk, I was interested partly in how Keteki would feel and see when not at home in Assam. I was also interested in having fun with an excursus of sorts in the chapter set in a Suffolk pub, the Rushcutters, and playing with a kind of early 20th century folk aesthetics, like in the novel Mr Weston’s Good Wine by T. F. Powys, or Stanley Spencer’s paintings.

As much as there’s light in the book, the socio-political structures and unpleasant childhood experiences make this one a dark novel, too. What was the purpose of writing this book for you? What did writing it do to you?

Anjali Joseph: I feel there’s a process through writing a novel of living and becoming the person who will have written that novel. So, I don’t think the novel exactly did things to me so much as allowed me to go through a certain journey. Two things stand out. One is the idea of revisiting the difficult past in order to release it and become lighter. The other is the simple idea of joy, as the orientation for life.

With regards to the phrase ‘keeping in touch’, there’s Mark with whom Keteki had worked a lot but doesn’t seem to know him well; Tuku’s world, again, remains aloof to the family; then there are many others in this short book … Would you agree that this story is an exercise in navigating chance, calculated, and desired connections?

Anjali Joseph: Connection is definitely at the heart of the story, and connection is both more intimate and more of the moment than the way we often think of knowing people, or even knowing ourselves. All of us are more like moving targets than our thinking takes into account, so keeping in touch makes more sense in that fluidity than any static idea of familiarity.

Keteki says in the book “when things are put into words, they lose some of their basic essence”. As a novelist, dealing with words is your business, how do you exercise restraint in a way that the ‘essence’ gets preserved when you are shaping the utterances in the form of writing? Also, is it really Keteki or you who says this?

Anjali Joseph: Keteki is expressing a principle that I think any artist feels, which is that it’s useful to concentrate on what you want to transmit, rather than on admiring the means of transmission. It’s also one of the basic principles of tantra, that what is fully described stops working.

It’s an interesting question for anyone making art, because I don’t know that this is an age where people are so attuned to any type of mystery, so in a way the immediate rewards are probably more emphatic for the kind of art that tells you what it’s going to do. Does it, then points out that it’s done it? I’m not speaking directly through the character, but I do agree with her.

Experimenting with career and life in general have become a serious venture for most people. But this adventure is now boring them. Were you trying to explore this conundrum via Keteki, who says, “The way things are, going off, helping other people with things, making them happy for a while, then starting again, it’s getting boring…People like me having around”? What’s this feeling, of trying to avert that you wanted to attract because it has now come to stay a bit longer with you?

Anjali Joseph: The part you quote is really about Keteki feeling a dissatisfaction with the way her presence seems to provide something to the people around her that she can’t completely experience. For her, avoiding continuity has been a way of life since her childhood. But continuity wasn’t available to her, just as in your larger question, the kinds of life that our parents or grandparents led where they may have had two or three jobs over a lifetime, is less likely to be the shape of things now.

Also read: Interview With Kritika Pandey: 2020 Commonwealth Short Story Prize winner

What did you find most difficult to do while writing this book?

Anjali Joseph: When I began the book, I liked the idea of publishing it quickly or even in a serialised form. I’d been re-reading Dickens and I was entertained with the way he composed long novels, pulling out different plot threads, introducing characters, and then picking up some but not all of those threads as he went on. I liked the idea of more immediacy. But that didn’t prove to be quite the way it worked; English language publishing probably doesn’t work like that in most cases, yet.

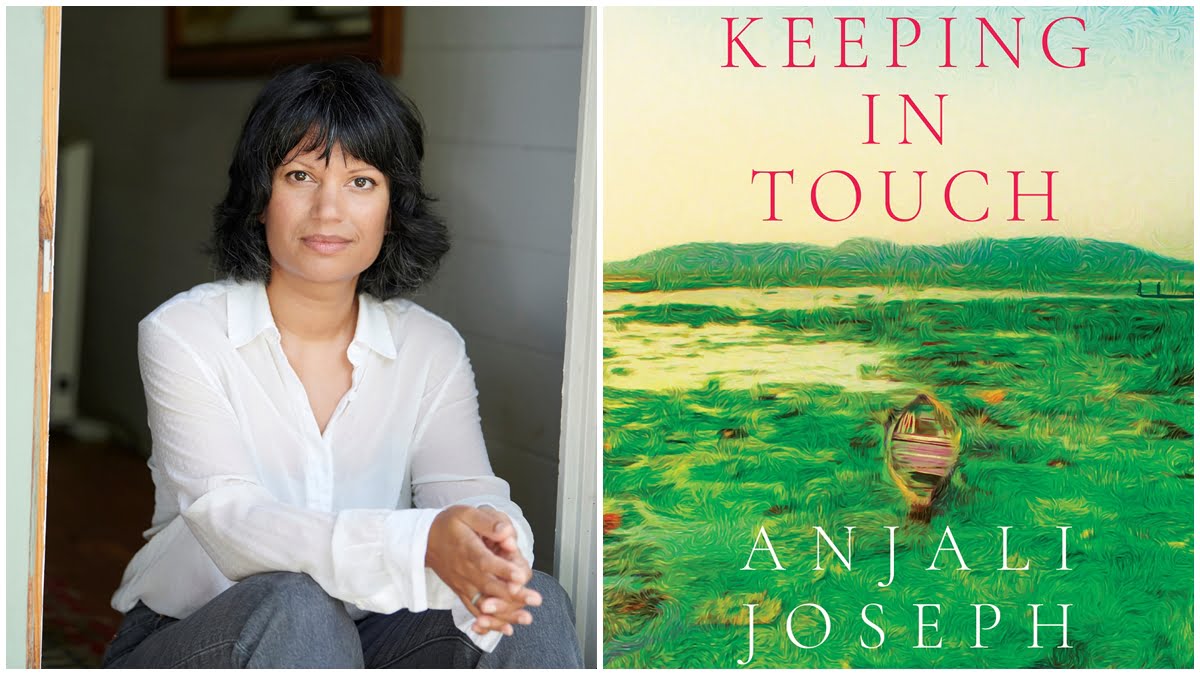

Anjali Joseph | Picture credits: Geraint

‘Keeping in Touch’ front cover | Picture credits: Context Books, an imprint of Westland Publications Pvt. Ltd.