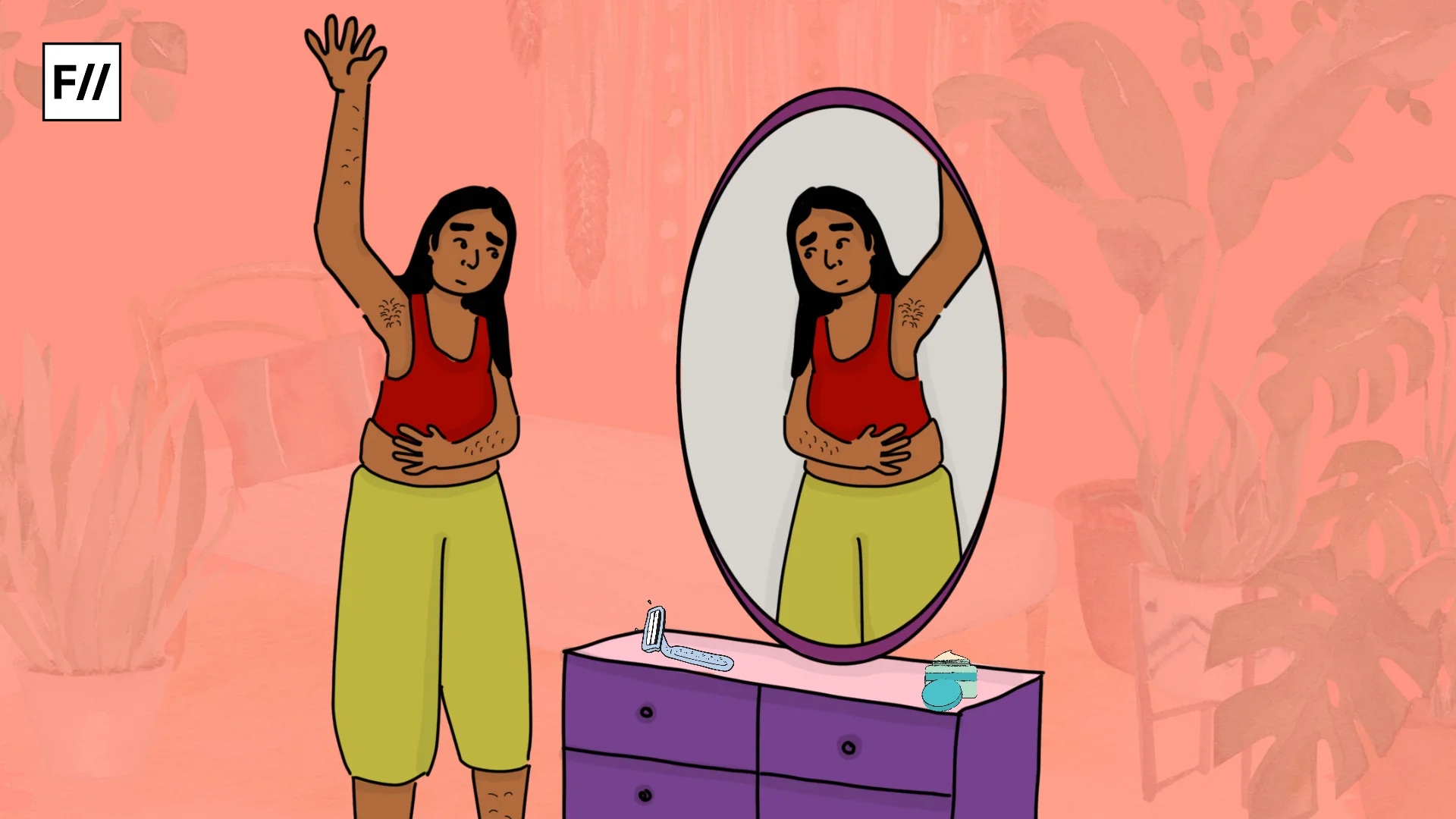

One of the important aspects of identity for many is body image. In the context of Indian classical dance scenario, body shaming is a factor that has been engrained into the dancers since times-immemorial: their bodies are often seen only in terms of consumption and catering to the predominantly upper-caste, upper-class and male gaze. Referring to my own experiences as a Odissi and folk dancer, I would like to elucidate upon body shaming and resultant influence on body image in the Indian classical dance scene.

In the context of Indian classical dance scenario, body shaming is a factor that has been engrained into the dancers since times-immemorial: their bodies are often seen only in terms of consumption and catering to the predominantly upper-caste, upper-class and male gaze.

I remember starving myself to a point where I would vomit and still go to the classes. This was until I realised that I have a certain body type and it’s completely natural. Instead of hating on my body for looking a certain way, I realised I had to embrace it, learn to function with and in it and adopt healthy habits for myself.

As a child, I did not know how to react to certain practices and norms that were bestowed upon me. I managed to somehow think that this is how the society is; that a dancer will be judged according to her physical appearance, mostly because a lot of her body is meant to look a certain way while doing specific movements. And movements would always be judged on the basis of how good your physicality is.

Also read: What Is The Society’s Problem With Male Classical Dancers?

Shastric norms for a dancer’s body

Though Shastras have defined what exactly a dancer’s body should look like, with changing times and evolving meaning of aesthetics, these notions were also subject to change. The body of a dancer is disciplined through various processes like exercises and balanced diet. Regular practice is another important feature of the training. Art forms like Kathakali too have various such body disciplining measures which are supposed to make the body fit for the dance.

When I would be done with my performance, along with appreciation from a few, there would also be a lot of surprised questions on, “How did I manage to be on that stage for an hour”? Apparently, I did not look like I could dance.

The societal stigma that a heavier person is not supposed to dance and instead, should should focus on shedding weight or look according to what the society thinks is a standard norm. However, I was undeterred and spent days and nights at the studio practicing and training to be fair unto the trust and confidence my teacher had bestowed on me and not give up.

Dance aesthetics or body aesthetics

The visual imagery has proven to be important for the connoisseurs to appreciate any art. The idea, at least when it comes to appreciating classical dance, is that what one sees should gives them pleasure. While this would mean aesthetically pleasing visuals, the truth is that real pleasure can be achieved only through purity of emotions and expressions. Often, young dancers attempt to copy the art form along with facial expressions of the great performers or artists they individually admire. But in this way, one is detaching oneself from exploring and internalizing dance. I have found how this adherence to conventional expression of emotions and lack of improvisation, in turn, restricts bodily autonomy. Different bodies behave and emote in different manners. Your facial and bodily behavior or expression may not be like of your or teacher/guru.

Since we live in our body, I found that I was constantly making calculations of my body weight, short stature, energy levels. I negotiated through many such painful occasions with my wit, humour and perseverance.

Since we live in our body, I found that I was constantly making calculations of my body weight, short stature, energy levels. I negotiated through many such painful occasions with my wit, humour and perseverance. Meanwhile, I was training my body to be an embodied spirit with the right amount of patience, understanding and determination required for a passionate dancer.

Also read: Nrithya Pillai: The Anti-Caste Dancer-Activist Progressively Reviving Bharatanatyam

Group ethno-aesthetics

My personal experience in the last 15 years is that of rejection and neglect in some of the major productions of the institute. I was made to feel that neither did I fit into the group sequences nor in solo enactments. I was continuously made to realize that my body was at fault, no matter what I did.

The industry is so focused on what dancers should look like. What happens to caring about their talent? Why does it matter if a dancer is a size double zero or size six, if it doesn’t affect her/his/their dancing? As dancers we have a lot of challenges coming our way, be it a injury that could stop our growth or career, be it financial constraints or dealing with conservative households where following art as a professional career choice is a big NO. Meanwhile, I have observed how dancers are rarely ever given a comprehensive and empathetic guidance on how to live a healthy life. The focus is more on the physical appearance of the dancer, to somehow fit their body into a mould of conventional perfection overnight. Instead of trusting on the dancer’s capability and artistic essence, the focus is on what could be consumable and will be good for the market.

In Conclusion

The thoughts and experiences tabled here are not just mine, but also reverberate with those of many who have either left their passion for dance or have had to succumbed to societal norms. The technicalities of dance can be easily learnt over a period of time but the deeper meaning and the essence, which goes beyond creating similar bodies and similar templates, takes determination, the will to change and of course, long standing practice.

Prachi is a Odissi and a Folk dance practitioner. She wishes to be a student lifelong. She has been training in dance for more than 15 years now. Post graduate in Gender Studies, she wishes to understand the Gender spectrum in the Artistic world and break the stereotypical perceptions among the Indian Classical dancers. She wishes to see dance from a different perspective and adopt new measures to educate young people. You can find her on Instagram and Facebook.

Featured image source: rotarynewsonline.org