Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September, 2021 is Parenthood. We invite submissions on the many layers of being parents, having parents and navigating the social norms of parenting throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Are you even a teenager in an Indian household if you aren’t accustomed to arguments? Loud, raging, and turbulent. These arguments aren’t just restricted to heated words; they sometimes also culminate in slammed doors, uneaten meals, and days without conversations. Combine all of this with the fact that the teenager is a ‘feminist’ and you have the perfect recipe for disaster.

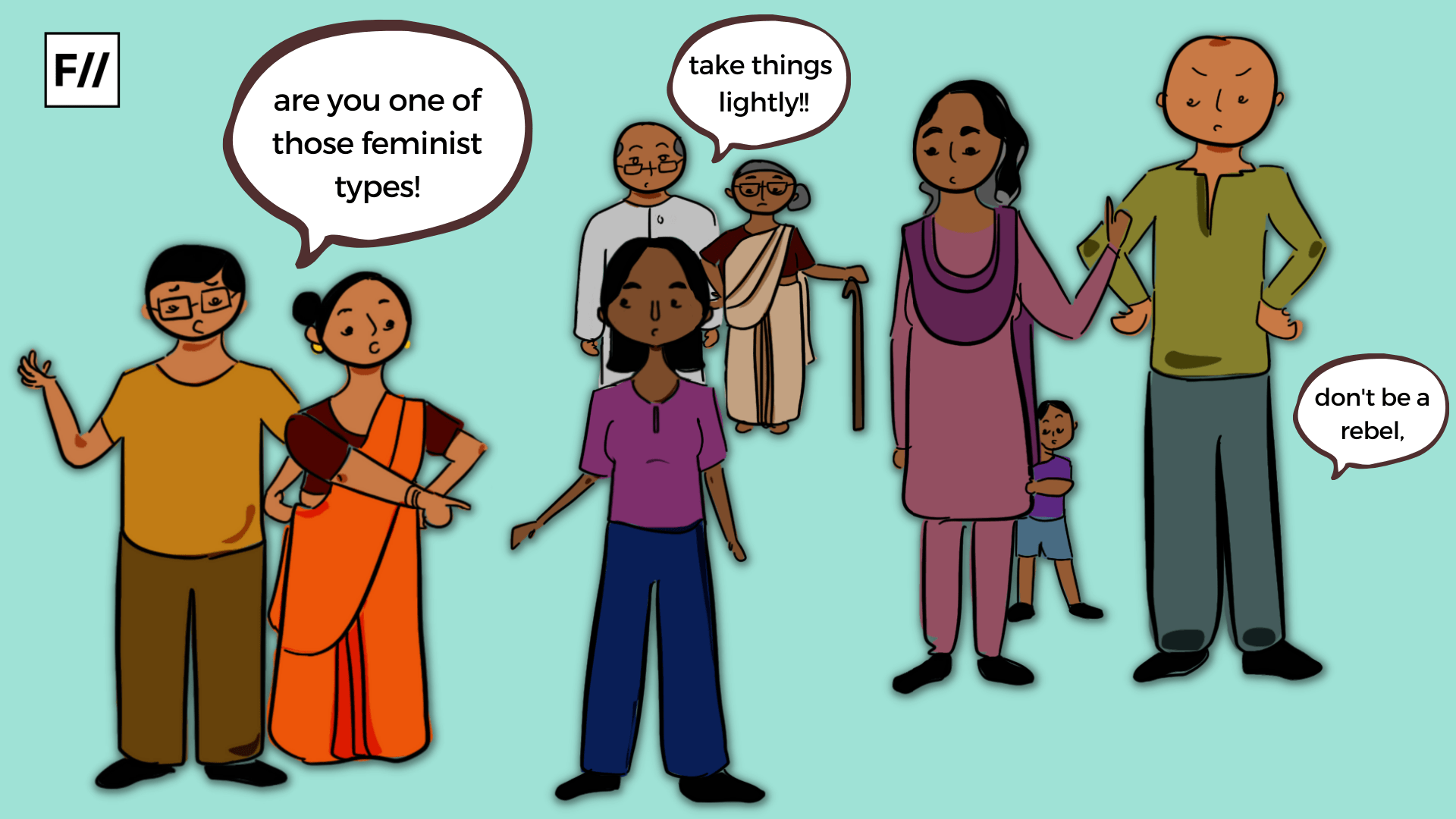

I cannot count on my hands the number of instances at parties and family dinners wherein I’ve been deemed a ‘rebel’ a ‘liberal’ a ‘feminist’ as if they’re all words to detest. As if I’m the kind of teenager that parents should keep their children far, far away from. My own household can be quite a havoc at times.

As a 19-year-old pursuing a degree in Psychology & Sociology, I have at my disposal a vast range of resources that allow me to read about the feminist discourse and discrimination towards my gender carried out over the years. We read and discuss the works of Judith Butler and ‘doing gender’ in class. We examine the ideas of Nivedita Menon and how gender-appropriate behavior is dictated in families within India.

I’m privileged enough to have access to these journals, books, and theories that have shaped what feminism is today. Albeit, my parents weren’t as fortunate— or unfortunate in their opinion— to have these avenues.

Therefore, when I speak of how I wish to take a walk while listening to my favorite music at 10 PM, I’m met with disdain from my parents. It raises questions like ‘Why would you even want to go out at that time?’ instead of addressing ‘Why are my cisgender male friends able to do so without another thought, reprimand, or explanation?’ How do I explain to them that the hierarchies in our society are designed to always favour the male?

The question of going out is most likely also met with moral policing of all kinds, which is also what a lot of social rules for the ‘protection of women‘ in the country seem to be based on. Imagine the proprietary, patriarchal validation that is fostered when a politician, or a minister of a state insults a woman and her choice of wearing jeans. The same problematic notion is reaffirmed when a state like Lucknow introduces AI-enabled facial cameras to monitor women.

It is hard to reason with parents when their ideologies and beliefs are so deeply rooted and intertwined with problematic evolutionary and religious arguments. They still believe that visiting temples while menstruating, for instance, is wrong because religion says so. They still believe that men and women are inherently different, have different innate and primal desires and characteristics, and are more drawn towards particular kinds of social settings

It isn’t unlikely then, how our thoughts on marriage, sexual relationships, and household chores continue to be drastically gendered too. As a feminist, I seek freedom, agency, and equality in these decisions. Whereas for the conservative family I am part of, these concepts are intimidating and unnecessary.

I argue frantically when I see another Whatsapp forward by my father degrading my mother’s cooking, physical appearance, etc. Needless to say, films like ‘Pyaar ka Punchnama’ and ‘Sonu Ke Titu ki Sweety’ have unfortunately perpetuated and normalised the stereotype of the ‘nagging, questioning, and irritable wife/girlfriend.’ When confronted about the same, his responses shift the blame on me, urging me to not be so sensitive and take things more ‘humorously‘.

As a feminist, if I ever were to have my own children, respecting their partners and never speaking to them in derogatory ways is perhaps one of the first things I would teach them.

It is hard to reason with parents when their ideologies and beliefs are so deeply rooted and intertwined with problematic evolutionary and religious arguments. They still believe that visiting temples while menstruating, for instance, is wrong because religion says so. They still believe that men and women are inherently different, have different innate and primal desires and characteristics, and are more drawn towards particular kinds of social settings.

Also read: Housework And The Normalisation Of The ‘Clueless Man’

From the moment we are born, we all look at different agents of socialisation for certain social cues that assist our behavior and ideologies. The most primary agents of the same are undoubtedly parents and our family members. Until we are past adolescence, we more or less tend to observe and react to situations in the same ways that we have been viewing them. Therefore, perhaps unintentionally, our parents too imbibe into us the same values that they have grown up with.

This is also why they’re so quick to give us examples of how things were in their times as means of comparison to freedom that women today relatively have.

We must have these difficult conversations with our parents. We need to make room for not just heterosexual identities, but also those from the LGBTGIA+ communities when we navigate feminist discourse at home. The future of feminism must be inclusive, and parents play a pivotal role in the same. So it is extremely crucial that we keep conversing about people from all kinds of intersectional identities to normalise personal agency beyond patriarchal dichotomies

I recall instances and stories of my mother being slapped by her father for returning to the house post 9 pm. I recollect stories of my grandmother being beaten if seen speaking to a boy and then married off at the age of 22. Women before us have grown up in a society where female emancipation wasn’t synonymous with liberation, but rather an irrelevant and futile exercise due to which men could potentially lose their economic, social, and historically powerful positions. Feminism was seen as a direct threat to their authority over women.

Thus, for my parents, watching these progressive strides occur all around them seems like another detrimental practice copied from the West. For them, watching me wear a dress and going to a party isn’t me exercising my rights, but rather something they cannot even imagine ever asking for in their childhood.

While there are still battles I have to fight every day to be regarded as an equal individual discriminated on the gender that I identify with, understanding the place my parents come from and accounting for their upbringing and social environment has made me better equipped to deal with things.

While the future still does look murky, it is not something that provides no room for improvement considering how these conversations are already evolving. I look forward to discussions rather than arguments with parents, where I can openly express my views. Change is imperative, but it isn’t something that is bound to happen overnight.

We must have these difficult conversations with our parents. We need to make room for not just heterosexual identities, but also those from the LGBTGIA+ communities when we navigate feminist discourse at home. The future of feminism must be inclusive, and parents play a pivotal role in the same. So it is extremely crucial that we keep conversing about people from all kinds of intersectional identities to normalise personal agency beyond patriarchal dichotomies.

Doing so ensures a better present, and also a better future if our generation is to become parents. Feminist couples raising feminist kids is truly something the world could use more of!

Also read: Generation Gap: The Conflicts And Occasional Joys Of Negotiating Space With The Elderly

Swara currently hopes studying Psychology could help her better understand this world, but also strongly believes that iced coffee is the answer to everything. She can usually be fond curating Spotify playlists or typing away on her Notes app. She is on LinkedIn and Spotify

Featured Image Source: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

Such a needful content!!