Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September, 2021 is Parenthood. We invite submissions on the many layers of being parents, having parents and navigating the social norms of parenting throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

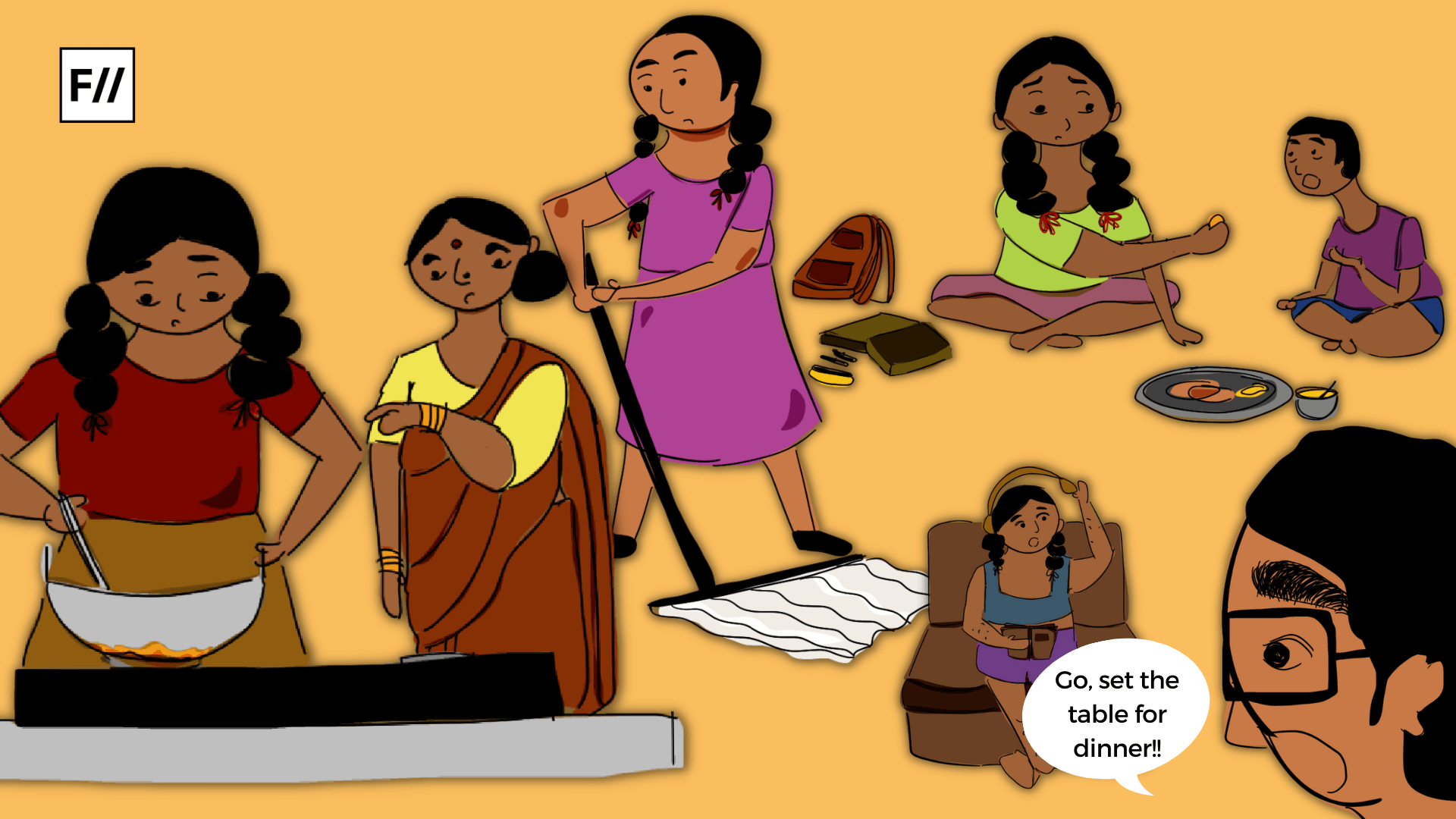

For me, the process of patriarchal mothering began when I was a young girl. I was in third grade when my grandmother — who was quite young back then — complained of a stomach ache. She was suddenly unable to function, or use the broom for cleaning as usual. My school had a holiday that day. As the daughter of working parents, I picked up the broom and started cleaning. After that, I used a wiper to mop the floor. My grandmother was proud. In the evening, I informed my parents, who were happy to see my ‘mature‘ behaviour.

During the lockdown, history repeated itself, but not quite in the same way. We decided to distribute domestic work among ourselves. My father and I took turns wiping the floor. Mother washed utensils. However, my younger brother, who was in sixth grade, didn’t do anything. Rather, he was told not to.

He wanted to wash utensils and mop the floor with a wiper, but my mother told him that ‘children’ should rather focus on studies. The opportunity to contribute to household work that was denied to my brother in sixth grade is the same for which I was praised in third grade.

This wasn’t really the first time. Since I can remember, I have not only hated cooking, but also been bad at it. My brother, in contrast, is a great cook. But, unlike me, he isn’t asked by neighbors, relatives, and parents to learn cooking. The justification for people’s unsolicited advice is that cooking is a life skill. Why, then, is that advice never imparted to young men? Why does my grandfather’s brother insist that I cook for him every time he visits?

Consequently, a woman’s career and life are expected to be planned ‘around’ the anticipated duties of a wife and a mother. It is what we are supposed to aspire for. This is in essence, a kind of social demand for the continuation of unpaid domestic work, often in addition to and at the expense of our work lives

This is what the patriarchal ‘mothering’ of girls and women is. We are expected to cook and clean, behave ‘properly,’ talk ‘softly,’ and choose a career ‘appropriate‘ for a conjugal life. We have to earn enough for our dowry, but not make more than our partner. These are the cultural instructions that by and large shape us, which is why unlearning is an ongoing process. The only purpose they serve is that of moulding girls and women into prospective, heterosexual wives and accommodating mothers.

If we tell our family members that we don’t want to marry, here’s the typical response: “Everyone says that, but you’ll change your mind.” If we say that we don’t want kids, then we are not “normal.” These comments don’t anticipate our behavioral transformation, but rather force it.

I don’t mean to imply that married women with children cannot be independent. What I mean is that marriage and children are seldom optional choices when it comes to women’s lives. The conditioned upbringing of women in Indian families often indoctrinates them into perceiving motherhood as an important, non-negotiable life ‘goal.’ This is why when a woman announces her pregnancy, the conventional response is, “Congratulations!” We invariably assume that the woman wants to keep the child.

Consequently, a woman’s career and life are expected to be planned ‘around’ the anticipated duties of a wife and a mother. It is what we are supposed to aspire for. This is in essence, a kind of social demand for the continuation of unpaid domestic work, often in addition to and at the expense of our work lives.

Also read: ‘Shakuntala Devi’ And The Patriarchal Trope Of The ‘Good Mother’

We need to stop glamourising the labour of mothers, or in fact glamourising motherhood itself. It must always be a free, independent choice of an individual rather than one that is slowly and steadily cemented into their psyche through repetition of socio-cultural gender roles that assert motherhood as the eventual destiny of every woman

The reward? The glorification of excessive work that is culturally perceived as part and parcel of a woman’s life and economically rendered invisible. It is estimated that Indian women spend around 297 minutes per day performing unpaid domestic work, while men spend only 31 minutes.

By dominating the conversation around motherhood, patriarchy succeeds in severely restricting women’s agency after their transition to motherhood. This doesn’t mean that mothers cannot have their own agency, but that largely the social protocols that dictate our upbringing are the ones that undo a woman to ‘make’ her prepared to be a future mother.

Motherhood has been normalised as so deeply integral to the life of a woman, that its experience often extends beyond the ambit of parenting. Its glamorisation or pedestalisation is not an indicator of concern for women, but rather a grossly exploitative measure to propagate the myth that motherhood is necessarily the choice of every woman.

Even celebrities like Kareena Kapoor Khan have published their books on the subject. Kalki Koechlin’s book on pregnancy is due for release. Most of these books are commodities that sell socially sanctioned ideas of motherhood. Their proclaimed ‘subversiveness’ is questionable, many a times.

Consider why the publication of a motherhood narrative by a person with disability or a queer individual is ‘interventionist.’ It is called so because the publishing industry loves to recycle and republish societal notions of motherhood, preferably written by people who conform to normative markers of social identity. That is why any book on the subject that is not written by a Savarna cis-het non-disabled woman is an ‘intervention.’ It’s not an intervention; it’s tokenism, which is profitable primarily to the publisher, who can now pretend to be ‘disruptive.’

Also read: Mothering: Glorified In Speech But Culturally And Politically Devalued In Practice

The public response to publications on this subject remains unchanged. We read, we speak about the physical and emotional toll of the process, we clap, but we don’t change. We don’t distribute work. We look for excuses. We like, share, and subscribe to videos, but we don’t establish a dialogue in our peer circles. We don’t listen. Have things really changed?

We need to stop glamourising the labour of mothers, or in fact glamourising motherhood itself. It must always be a free, independent choice of an individual rather than one that is slowly and steadily cemented into their psyche through repetition of socio-cultural gender roles that assert motherhood as the eventual destiny of every woman.

Author’s note: This article features personal examples. My understanding of this subject is largely an outcome of personal experiences and academic study. I realise that this perhaps constitutes only a fraction of the lived experiences of several non-males. I do not wish to speak on behalf of people with other gender identities because I cannot claim their experiences

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a researcher and a writer. Her work lies in the intersection of feminist theory, postcolonial studies, and popular culture.