Precisely a year ago, a Dalit teen girl was gangraped in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh. She succumbed to her wounds two weeks later especially because of delayed medical care and hospitalisation. Her case caught attention when a few political parties began to demand justice for the Dalit girl especially when she was constantly denied medical care. The saga turned horrific when the authorities decided to cremate her body in the dead of the night on September 30 without the family’s consent. The morning that followed was painted with a nationwide protest that demanded justice for the victim.

The case deeply stirred the moral conscience of the nation and the media decided to camp out at the Uttar Pradesh village. Opposition parties came in support of the lower caste victim, even as many Hindu fractions marched in support of the four Thakur boys who were accused of the rape. The humdrum fell silent in about a fortnight and the world moved on. Exactly a year after her death, the case is still dragging in the courts, her family is living caged in their own home, the caste divide in the village has deepened and the other Dalit girls fear for their lives.

Opposition parties came in support of the lower caste victim, even as many Hindu fractions marched in support of the four Thakur boys who were accused of the rape. The humdrum fell silent in about a fortnight and the world moved on. Exactly a year after her death, the case is still dragging in the courts, her family is living caged in their own home, the caste divide in the village has deepened and the other Dalit girls fear for their lives.

Also read: Caste Impunity Vs Legal Protection For The Hathras Rape Victim

The Case

On September 25, 2021, the Allahabad High Court asked the Uttar Pradesh Government to specify if it had framed a scheme as envisaged under Subsection 11 of Section 15-A of the SC-ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act 1989. A year on and the case still drags through the peeling walls of the Indian judicial system. The family has been paid compensation but refused pension, house, agricultural land, and job to a family member.

The delay in justice and the technicalities the case gets wound up in has diminished the hope for justice for the victim’s family. Seema Khushwaha, the victim’s lawyer complained that on March 5, 2021, some drunk lawyers created a ruckus in the courtroom and passed lewd comments. When the victims’ undergarments were produced, they started screaming “Acche se dikhao” (Show us properly). They tried to intimidate the lawyer and vowed to teach her her place if she doesn’t quit the case, “Seema ko seema yaad dila denge”.

The Family

The family has been living under careful protection overlooked by around thirty CRPF personnel. They have received the protection they were promised but have been denied basic respect. It has been exactly a year and they have been caged in their own home. The family is not allowed to step out of their home without an escort, even for their daily chores. The vegetable vendor is summoned by the CRPF at their gate, a trip to the barber is also under strict surveillance, anyone entering or leaving the house has to make a formal entry in the register maintained at the gate. The relatives of the family have also stopped coming because of the strict procedure.

The family has not yet been able to submerged the ashes of the victim. Her mother cries at the sheer regret she harbors for not being able to listen to the cries of her daughter that day. The victim’s sister-in-law is angry at the police for cremating the victim without the family’s consent. She says that they weren’t shown the face of the young girl, they don’t even know if the ashes belong to the victim. The saree the victim’s mother wore on the morning her daughter was cremated hangs from the veranda’s ceiling. The family awaits justice.

The brothers are summoned at the court and are harassed. Any source of income of the family has dried up as they cannot step out of the house. The compensation money is being spent on daily expenses and court appearances. The fight for justice has not only tested their physical and mental strength and exacerbated the caste-based oppression they were facing, but has also threatened their future. The victim had three nieces who are being brought up in constant fear. They have resorted to befriending the CRPF personnel posted outside their home. Their childhood is being spent trapped inside the four walls of wailing, hope, and poverty.

The Caste Divide

The victim’s village Boolhgarhi has 66 households, most of which belong to the upper castes community; including the Thakurs and the Brahmins. There are only four Dalit families, and that are confined to the dirtiest lanes of the village. The oppressed caste communities are literally divided by a road and garbage, which is now under 24-hour surveillance. The cleaner section belongs to the upper castes that harbor a temple where the Dalits are not allowed.

The gangrape shook the village and taunted the upper castes. The conviction of four Thakur men has enraged the villagers who blame the girl. Majority of the village lives in denial and still blames the victim. They believe that the case is only a ploy to malign the reputation of upper-caste men. The three other Dalit families reportedly live in constant fear.

The Other Side

The four Thakur boys accused of gangrape have been jailed for a year now. Their fate also depends on the trial that has been dragging. They are not allowed to meet their families on the pretext of the pandemic and their phone calls made home are consumed by crying for their innocence. The victim had named Sandeep (20), Ravi (35), Ramu (26), and Luvkush (23) in her dying declaration and the CBI charge-sheet also names them as the accused of gangrape.

The four accused had written a letter to the SP of Mathura in which Sandeep confessed to being involved with the victim. They maintained that the victim’s death was a case of “honor killing” after the brother had discovered their affair. The upper-caste women of the village also believe the men and deny any rape: “Why blame the men? Maybe she also wanted it.”

A Rape “Waiting To Happen”

The victim’s friend spoke to NewsLaundry after a year of the incident. She recalls how the victim had mentioned Sandeep harassing her before the incident. The victim had complained of how the accused grabbed her and she was scared to go out of the house. The Dalit girl confirmed that the accused held a reputation of eve-teasing women from their village and other villages. The friend further recounted her horror when she was teased by Sandeep, “I mean…Initially, they used to just eve-tease us whenever we passed by. Sandeep would call me ‘Katrina Kaif’. I tried not to bother much.”

The victim had complained of how the accused grabbed her and she was scared to go out of the house. The Dalit girl confirmed that the accused held a reputation of eve-teasing women from their village and other villages. The friend further recounted her horror when she was teased by Sandeep, “I mean…Initially, they used to just eve-tease us whenever we passed by. Sandeep would call me ‘Katrina Kaif’. I tried not to bother much.”

Even as the Hathras victim’s family laments their ignorance and wishes they had known about it earlier, the truth of the Dalit girl reflects a microcosm of the society we live in. After a year of the incident, the village quietly witnesses under mounting discrimination against the Dalit families, a constant state of fear of media trial, and an ambiguous future. The political parties that had stormed in for a photo op have forgotten about the village ever since. The media has moved on and Dalit women continue to be raped. A year since Hathras, justice appears further away and social stigma has worsened, if anything.

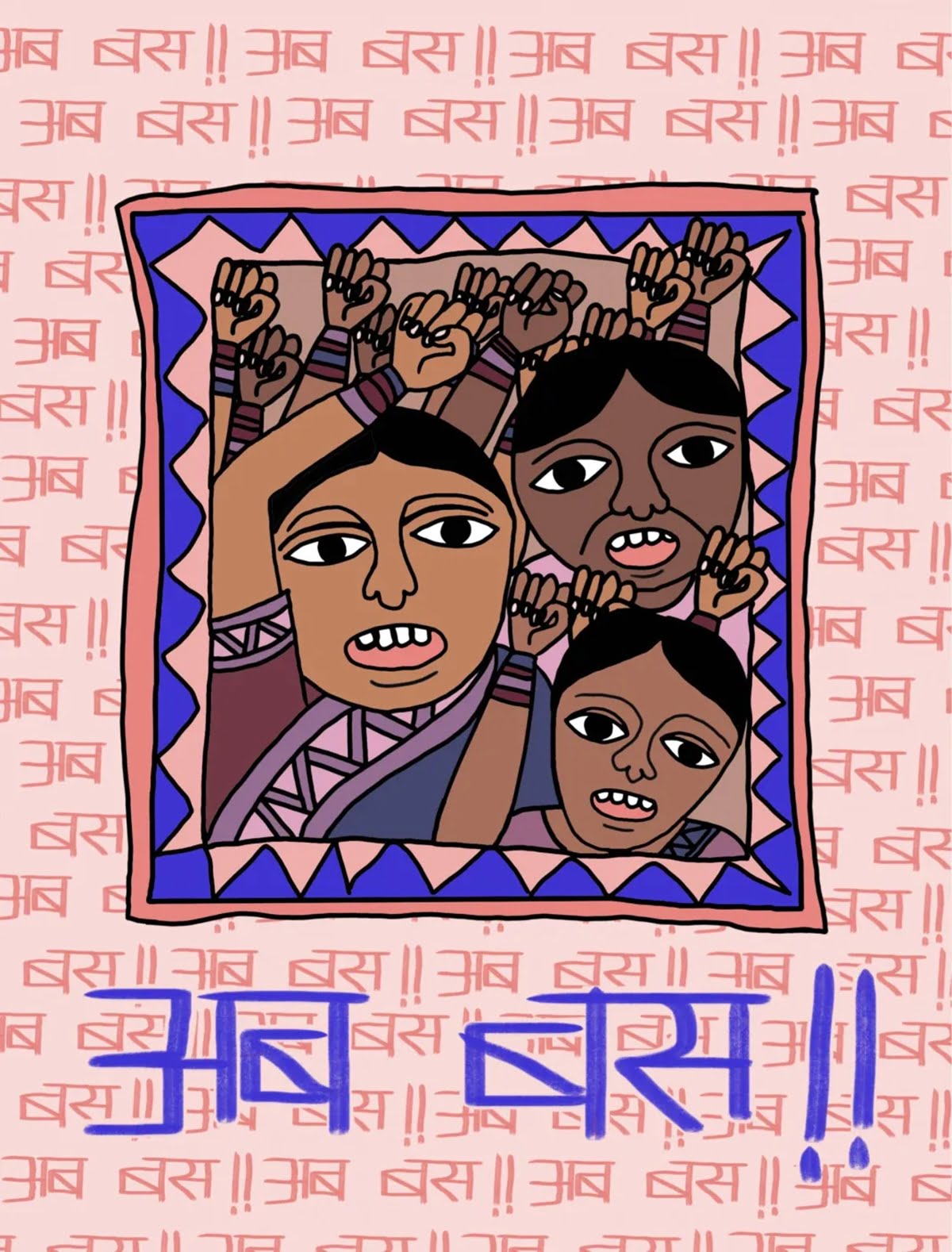

Featured Image Credit: Sunidhi Kothari/Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Dr. Guni Vats is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies. A PhD in Gender Studies, she is a renowned researcher, writer, and scholar.