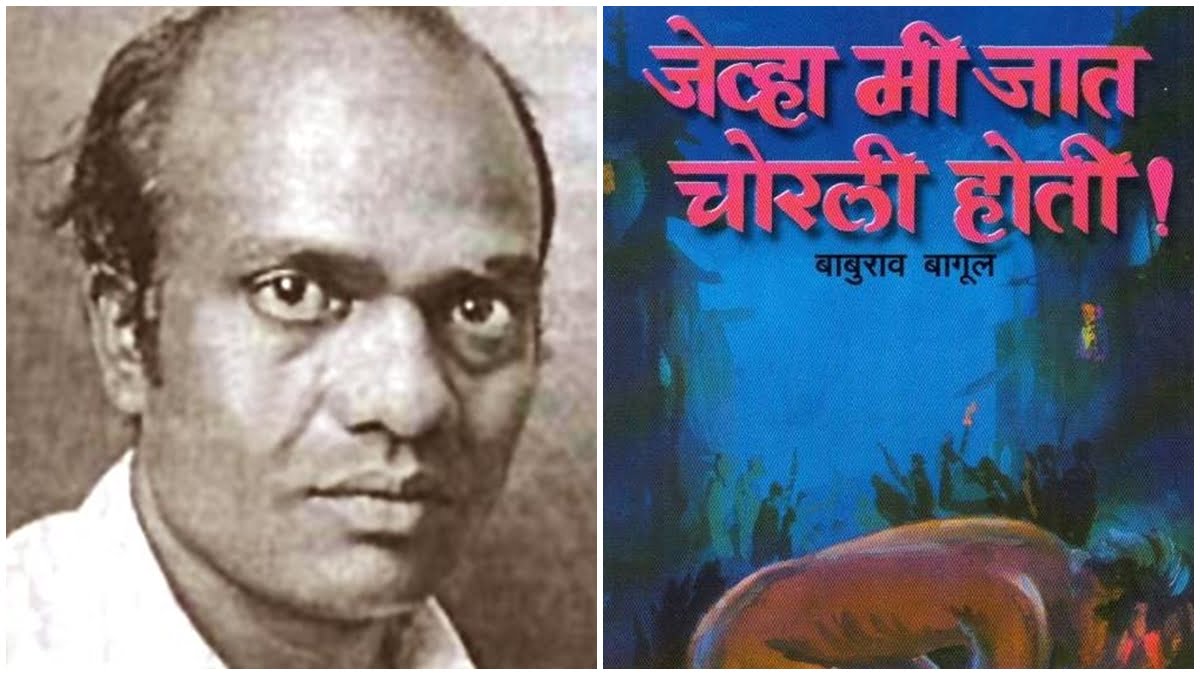

Baburao Bagul wove his stories keeping in mind the intersections of caste, gender, and class. His collection of stories called When I Hid My Caste (Jevha Mi Jat Chorali) 1963 is an important contribution to modern Marathi literature. For his subject matter, instead of dealing with just class in isolation, Bagul’s focus is more on caste and gender and the double marginalisation that people suffer on account of it. Being a part of Dalit Panthers group, his writings were Ambedkarite, Marxist, and anti-establishment in nature. The Dalit author wrote about the marginalised downtrodden section of society and exposes the world of systemic oppression. He is among the enlightened writers who authentically depict the ordeals faced by women in a patriarchal and caste ridden society. The intersectional feminist strain in the stories of Baburao Bagul might often seem as a matter of epiphany for upper-class feminists who would tend to miss out on the aspect of class and caste when it comes to feminist politics.

The Dalit author wrote about the marginalised downtrodden section of society and exposes the world of systemic oppression. Baburao Bagul is among the enlightened writers who authentically depict the ordeals faced by women in a patriarchal and caste ridden society.

In this article, I have dealt with the female characters in Baburao Bagul’s collection of stories, specifically The Prison of Darkness, Streetwalker and Monkey. I have dealt with the characters of Banoo from The Prison of Darkness, who is a woman from a oppressed caste woman and a widow, Girja from the Streetwalker who is a sex worker trying to save money for her son, and Sakhu, who is the victim of the atrocities of her husband and mother-in-law.

Also read: Shailendra: Portraying Complex Realities Of Common Lives

Prison of darkness

In “Prison of Darkness”, Banoo is a oppressed caste woman who is attacked by the villagers who accuse her of being responsible for the death of her husband, Ramrao Deshmukh. Through her character, Bagul exposed the operations of patriarchy, dehumanisation on account of caste, and the huge role of gender in magnifying one’s vulnerability in society.

After lighting his father’s funeral pyre, Devram, the step-son of Banoo is more occupied with the desire for revenge than grief. Banoo is the target of Devram’s revenge and is supported by the whole village. The villagers call her a witch who killed her husband with black magic. When her husband was alive, no one in the village dared to degrade her on account of her caste but after her husband’s death she is no more protected. The whole village is ready to take revenge upon her which is also mixed with perverted desire.

“‘Bring that demon here. Let’s strip her naked and take her in procession through the village,’ said Kanhuji Patil.

‘No, let’s strip her naked and tie her up like a null and whip her and lead her by the nose to the pyre,’ said Satva Sonar, in a fine fury.”

Even the Police Patil, whose duty is to maintain decorum and go by the law, says that he would be able to shrug Banoo’s death under the carpet on the false account of her committing sati. The hatred of villagers makes Banoo doubly marginalised because of her lower caste status as well as being a woman. Merely asking water from a Brahmin’s household is seen as a blasphemous act. While Daulat, her son, faces oppression only on account of his caste and not gender, Banoo has to face it on account of being a lower-caste woman.

When Devram finally is in front of Banoo to kill her, then his perverted desire also surfaces.

“He could not decide whether to make Banoo pay for the suffering that had killed his mother or to make love to her. With each glance, he was seized again by a new aspect of her beauty.” Banoo here, is seen as an object of revenge as well as desire. When Devram is stripping Banoo’s clothes, Kamala, Devram’s mother stops him not because she wants to save Banoo, but because she is afraid that Devram might get possessed. Here, Banoo is seen as an “Other” by everyone in the village when she is running the streets calling for help. When she is running on the street, and calling out Daulat’s name, an old woman curses her saying,

“Slut, whore, a woman like you has not been born in all the three worlds. And one is not likely to come along again either. You drove your own son mad because of the sin of his birth. When you got pregnant again, you thought your husband might stray and so you had an abortion. Now bear the fruit of your sins.”

The repetition of “you” and the innumerable blames put on Banoo make her the source of all tragedy. Her mere existence and transcendence of her lower-caste space is seen as the root of all the tragedy that has ensued in her life. When at the end of the story, Daulat kills Devram when Devram is stripping Banoo on the streets, it is seen as symbolic of the victory of maternal love.

However, there is also an element of internalised patriarchy in Daulat when he curses his mother and holds her responsible for his life. Even though she is avenged by her son, her son also humiliates her and thinks of her as his possession whose honor was being stripped. It was more out of his ego as a man than love for his mother that he killed Devram.

Streetwalker

Girja is a sex worker who struggles to keep up to the standards of society that bog her down every step of the way. She is vulnerable and most prone to exploitation. The psychological trauma that she faces to earn a few rupees to meet her son is excruciating. Girja is not seen just as an object of desire, but rather as a human being who is ready to go to any extent to be able to meet her sick son. Baburao Bagul has highlighted the psychological and emotional aspect of the life of sex workers, and how the dire economic conditions faced by Girja compelled her to don a seductive attire, and beautify herself against her turbulent emotional state. Her dilemma is summed up in these lines,

“But for some reason, it did not work; her lips would not redden. Her face would not brighten. Her mind would not lighten. Her gait had no spring in it. There was no sparkle, no spark to her. For her heart was sad.”

The story also deals with how another woman becomes a threat to her because of her share of money that will be diverted towards her competition.

Also read: The Epic Of Dalit Literature: When I Hid My Caste By Baburao Bagul

“She was no longer worried about the new girl. She had prayed to Baba for herself and she had prayed that her competition should be ruined.”

The story is a depiction of the fact that underlying all oppression and all deprivation, is the socio-economic aspect. On top of that, being in such a vulnerable position as that of a sex worker, makes Girja an easy target of exploitation. Her client tires her body physically to the point that she loses her consciousness and wakes up to find that the person had cheated her, and took away all the money that was rightfully hers. Her work was not paid for, because it is not seen professionally as other forms of work. The ultimate tragedy with Girja was that her son had already died and she had been lied to by the restaurant owner.

“Her son had died.

He was dead.”

Monkey

Sakhu is a married woman whose husband, Bapu Pehelwan is set to win a wrestling match. Sakhu is made the target when Bapu Pehelwan loses in a wrestling match. Sakhu is seen as a distraction, a lusty witch who would ensnare her husband in her trap and thus lead to his defeat in the wrestling match by a lower caste person. While Bapu was pining for Sakhu, she was also pining for her husband. But it is only her desire in the end which is the target of blame. Once he had broken his vow of celibacy one day before the match, he beat Sakhu for his own actions.

“When he realized that he had now broken his vow to remain celibate, rage exploded in his heart. Gathering all his strength and willpower once again, he threw her away from him.” Throughout the story, Sakhu becomes the punching bag of the mother-in-law and her son. Her desires are not accounted for, and her body is seen as a distraction from the reality principles of life.

Banoo, Girja, and Sakhu are all on the extreme margins of society. Baburao Bagul exposes the on-ground reality of the systemic oppression faced by these women. The literary scene of late 20th century Indian short stories was revolutionized by Bagul through such female characters who belong to the lowest rungs of society. He broke away from the tradition of writing which saw the division between poor and rich as only economical, and brought to fore how oppression is related to caste as well as gender. His works have been pivotal in ensuring the marginalised sections a space in literature, especially the downtrodden women who suffer in both public and private spheres.

Baburao Bagul’s works, which are originally written in Marathi and not in English, helped widen the reach of literature to local and vernacular circles, making reading accessible in a language that native people can understand. His stories are a constant reminder of the atrocities carried out on women and other marginalised sections. The stories spur the readers’ conscience to reflect upon the society we live in.

Even though Baburao Bagul gives voice to the doubly-marginalised women, his work does not include the plight of transgender and non-binary people, whose point of view has still not been reclaimed in Indian short stories. Nevertheless, his works which are originally written in Marathi and not in English help widen the reach of literature to local and vernacular circles, making reading accessible in a language that native people can understand. Baburao Bagul’s stories are a constant reminder of the atrocities carried out on women and the marginalised. The stories spur the readers’ conscience to reflect upon the society we live in.

Arifa Banu is currently doing her Masters in English Literature from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She has written several research papers on Postcolonialism, Feminism, and Indian Literature. Her research interests are South Asian Literature, Posthumanism, and Dalit Literature. You can find her on Instagram and Facebook.