The cases and incidents of discrimination against platform and gig workers have seen a rise in the recent times. Moreover, Covid-19 has exacerbated the misery and vulnerabilities of gig workers employed by various companies. Crucially, the gig economy offers a promise of equality to its workers in India’s competitive labour markets to graduates who may find it easier to get gigs than conventional jobs without work experience or class/caste networks, opportunities to work from home and to women constrained at home to whom gigs are opportunities to monetize their skills at a time and place of their choice. Platforms like Swiggy, Zomato, Uber, Ola, Urbanclap among many others have come to become primary players in the gig economy.

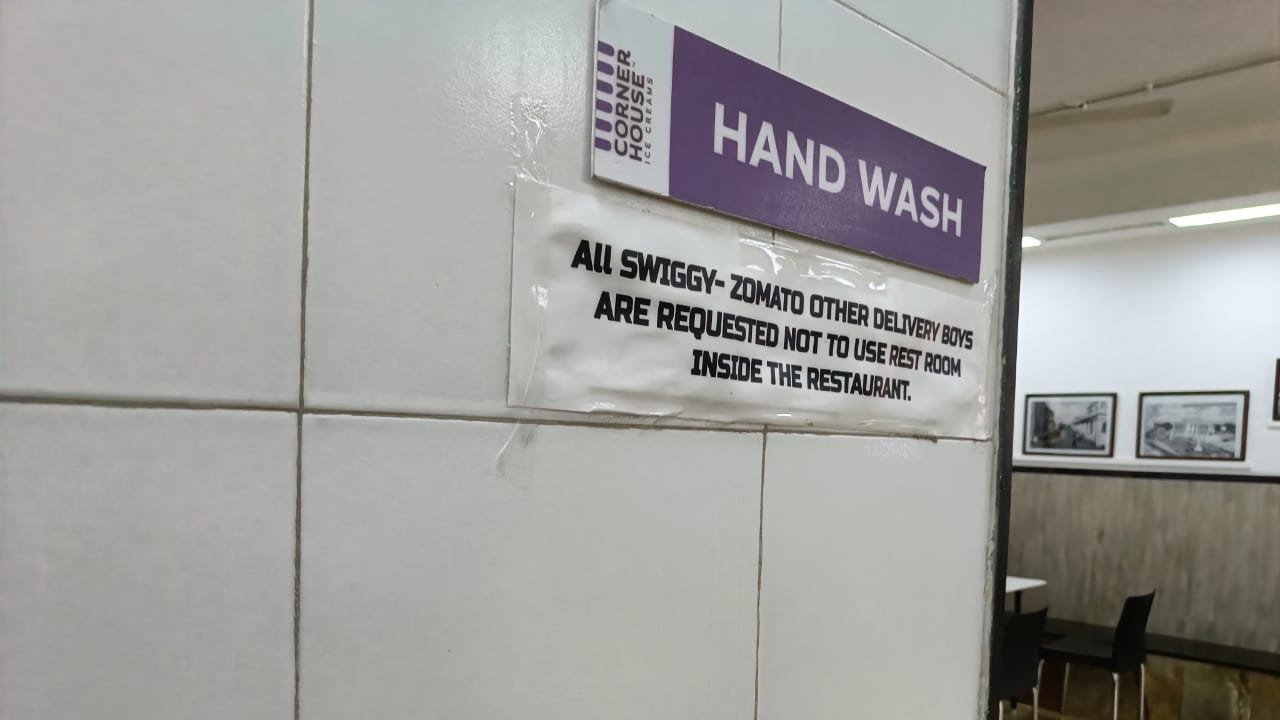

A gig or platform-based workplace provides a short term contractual form of employment, distinct from the conventional organised sector. However, in India gig work also translates to the culmination of labour-based discriminatory practices embedded in the realities of caste, race, gender and class. The recent incident reported by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union on Twitter saw that the Zomato and Swiggy delivery workers were denied access to public washrooms within a restaurant.

Also read: The Struggle Of Beauty Workers In On-Demand Digital Platform

In India gig work translates to the culmination of labour-based discriminatory practices embedded in the realities of caste, race, gender and class. The recent incident reported by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union on Twitter saw that the Zomato and Swiggy delivery workers were denied access to public washrooms within a restaurant.

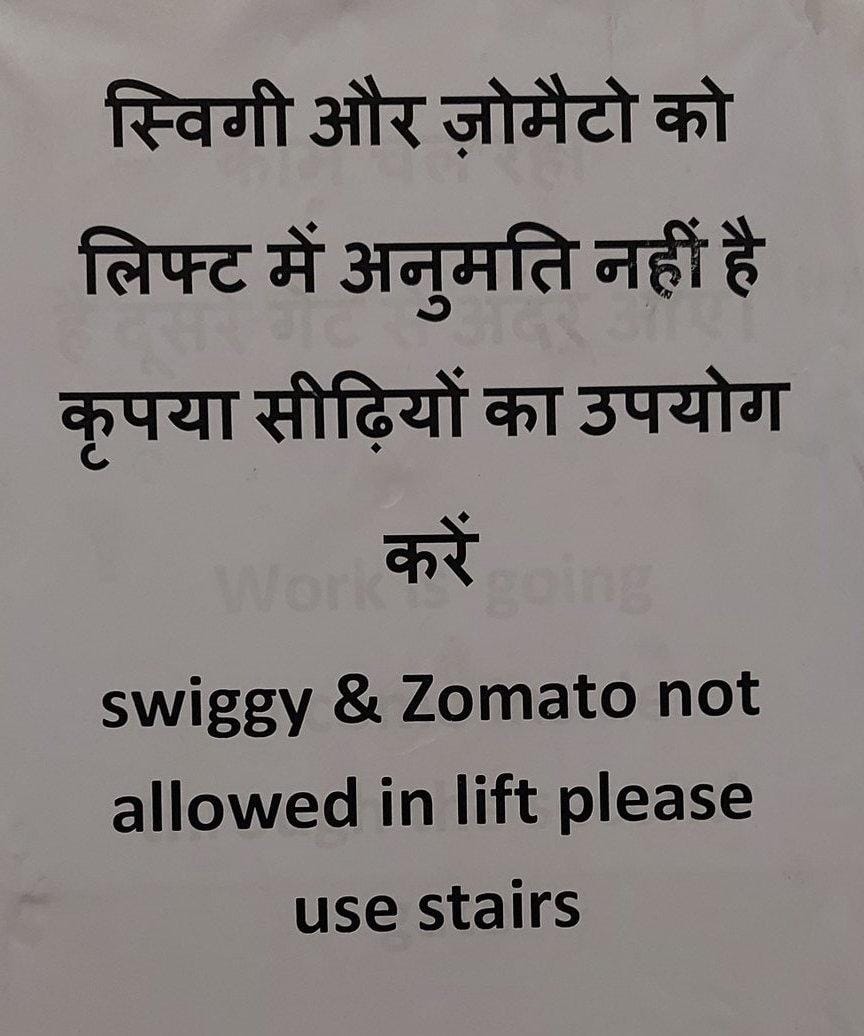

Similarly, another case of delivery workers providing services was reported wherein the workers were denied access to the lifts in a mall located in Jaipur, Rajasthan.

The Brahmanical notion of ‘purity and pollution’ assigned to the bodies of the workers is manifested in the modern agraharas of the workplace and domestic household. We also understand how labour performed by domestic and gig workers is largely perceived in a modern Brahmanical society.

The Brahmanical notion of ‘purity and pollution’ assigned to the bodies of the workers is manifested in the modern agraharas of the workplace and domestic household. We also understand how labour performed by domestic and gig workers is largely perceived in a modern Brahmanical society. Thus, even though one observes an occupational mobility from traditional caste bound roles, the virtue of ‘pollution’ assigned to the bodies of workers in these occupations reflect the hegemony of Brahmanism within the system. In the gig economy, the feudal bourgeoisie capitalises on the economic vulnerabilities and social insecurities of domestic and gig workers.

Another incident from 2019 reports that a Hyderabad resident was charged for refusing to accept his order from a Muslim delivery person working for Swiggy. While placing his order, he wrote in the special instructions that the delivery service should provide a delivery person who is Hindu. He had written: “Very less spicy. And, please select Hindu delivery person. All ratings will be based on this”. The digesting casteism and communalism of the Hyderabad resident provides evidence of the pervasive morality of ‘purity’ extended to the matters of food. It is important to note that these platform-based workplaces enjoy immunity from the lack of accountability for such discrimination. Due to the structure of the gig economy, companies are not liable to prejudices practiced against the workers.

Many believe that the only difference between the 21st century and ancient feudalism is its working on the digital landscape. The nature of appropriating coercive powers is reflected in the designing of service apps like Swiggy, Zomato, Uber etc., which make the users feel that the world revolves around their convenience. The feeling that the sharing economy is basically a rent extracting economy of the highest order is still being uncomfortably accepted. Based on arbitrary metrics with no accountability, the customers now have the power to wield ‘rating’ as a form of coercion and control over the workers. Further, the rating system is leveraged by customers to blackmail gig workers for extra labour. Since there is no employer-employee relationship, the gig workers are denied a stipulated and fixed remuneration, have to work for longer hours and bereft from any form of social security that an employee enjoys.

Recently, Grofers, an online grocery service, was held accountable after many noticed how their ‘promise’ to deliver groceries within 10 minutes meant grave exploitation of the workforce employed with the organisation.

A biographical study of these gig workers reveals that traditionally their identities have positioned them outside the formal labour market, forcing those devoid of caste and class capital to undertake undesirable gig jobs. These workers who are categorised as independent contractors instead of employees, are made to exist in a vacuum, not covered by labour protection which then makes them vulnerable to discrimination on the basis of their sex, gender, caste and class location.

Another study informs that individuals from the marginalised communities take to working for these platforms as it enables them to participate in occupations that eschews the traditional form of social discrimination from their life. The study reported that the workers from minority religious communities, the Banjara caste community categorised under Scheduled Tribes and others living in economic ghettos ‘grab’ these opportunities as they believe them to be sans discrimination. Nevertheless, the prominence of such incidents only tell us that social disparities are aggressively reinforced within the so-called ‘sharing’ economy as well.

Quoting Varadarajan, a food delivery executive from Chennai, the Hindu writes that “In restaurants, we are looked down upon as uninvited guests. There are people who won’t even share an elevator with us. In case of an accident, the delivery person is always held at fault.” Such accounts indicate to us the precarious realities of caste and class transpiring in the corridors of a sharing economy.

The segregation of workers in public places and the lack of access to basic amenities like washrooms and lifts revive a modern day nostalgia of medieval casteism. The social ostracisation strikes home especially when there are no formal safeguards to protect the workers against discrimination. Further, the negligence to address these prejudices have lead to many delivery personnel losing their lives in road accidents. This calls for immediate attention from both the private and public stakeholders at play.

To invisibilise the implications of primitive communalism and casteism is perhaps a convenient measure to parade the so-called modernity and progress of our nation. The dignity that a Brahmanical system in India fails to attribute to certain forms of labour, calls not only for an economic redressal but also a social one.

The social structure of India has historically been a site for ostracisation of the marginalised communities. The orthodoxy of India’s social structure is prevalent in the capitalist neo-liberal system, exhibiting new forms within the modern socio-economic infrastructure. To invisibilise the implications of primitive communalism and casteism is perhaps a convenient measure to parade the so-called modernity and progress of our nation. The dignity that a Brahmanical system in India fails to attribute to certain forms of labour, calls not only for an economic redressal but also a social one.

Featured image source: Tech Circle